A longer version of this article first appeared in Staffordshire Life November 2017 – Sara

Most of us are familiar with having our pulse taken routinely as part of any examination at the doctor’s. Medics use the second hand on their watches to time a minute and record the number of beats in that time. Feeling for the speed of the pulse to diagnose certain conditions goes back to ancient times and is discussed in the Hippocratic writings in the fourth century BCE. Fast forward to the early seventeenth century and the first attempts to record the number of pulse beats accurately became possible because of a device called a pulsilogy made by the Italian physician and inventor Santorio Sanctorius using a pendulum and a scale ruler.

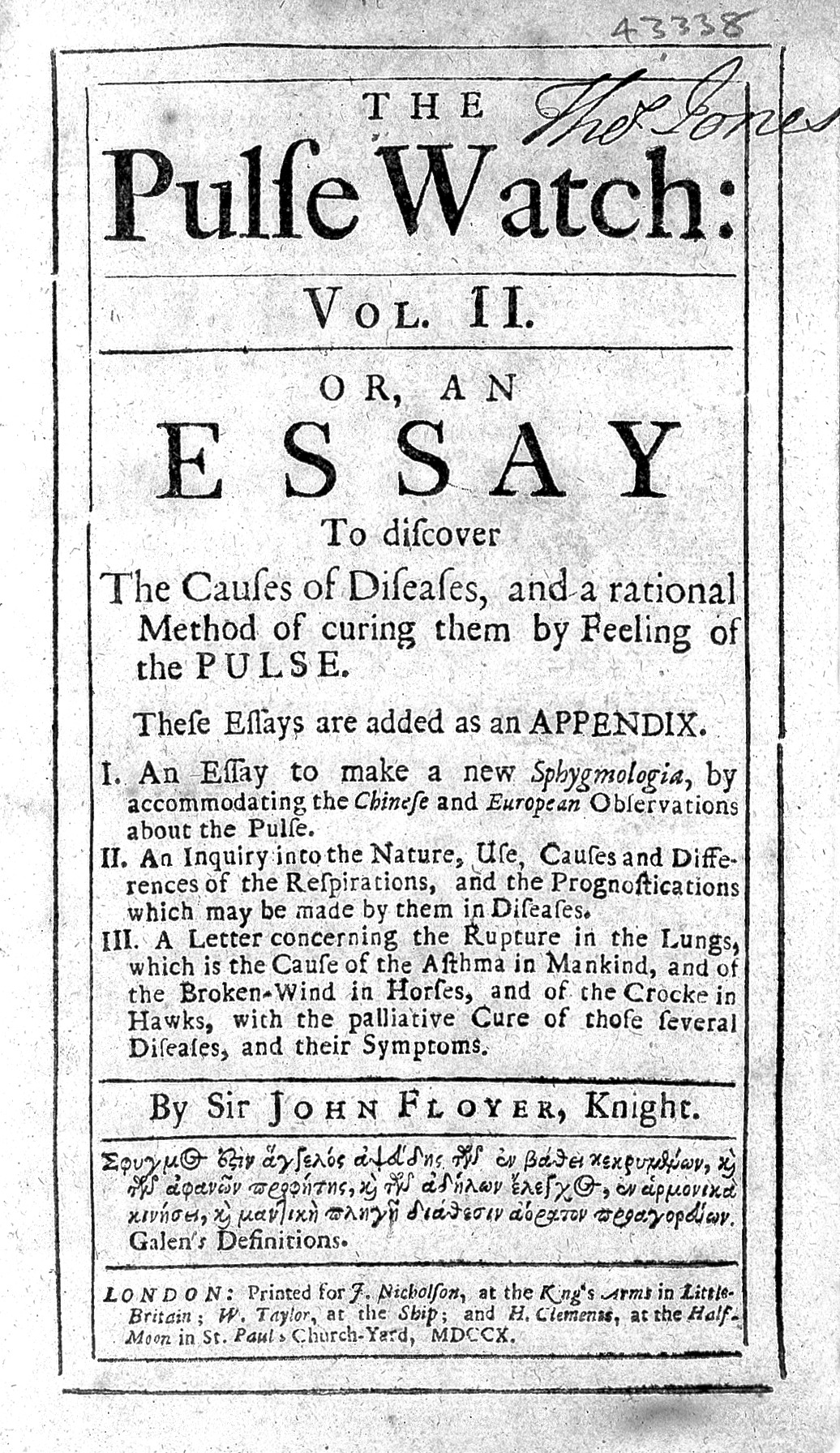

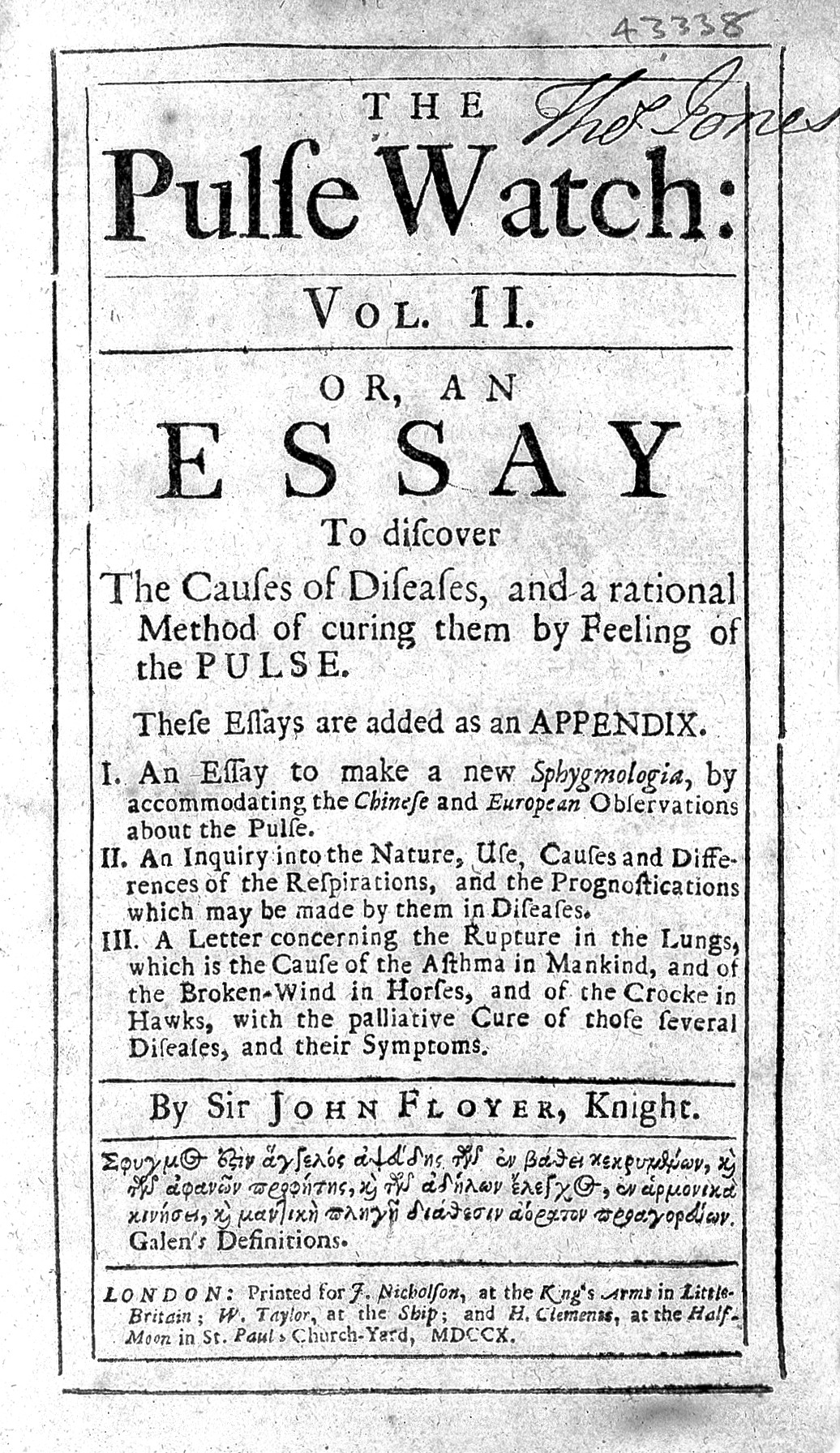

Around a hundred years after Sanctorius’s invention, a physician born in Hints outside Tamworth and who practised in Lichfield in Staffordshire, Sir John Floyer (1649-1734) designed a special watch and developed the counting system which became the routine observation most of us are familiar with. In 1707, in London, he published a 466 page book about the pulse and his pulse-watch, with the fittingly long title, The Physician’s Pulse-watch; or an Essay to explain the old Art of Feeling for the Pulse and to Improve it by the Help of a Pulse-watch. The book was dedicated to Queen Anne, and in 1710 the second volume, this time a running to 510 pages was printed.

Included in the book’s findings was a table of the pulse tests performed in Lichfield the previous spring. ‘The pulses of divers old Women taken in the morning Fasting [i.e. before having anything to eat] at the Hospital in Lichfield last May’. Floyer included a note that age wasn’t the only factor in the number of ‘pulses’ an ‘old’ woman (who ranged in age from 50 to 86) might have, but that ‘different Constitutions, and Diet, and Passions’ would all have a bearing. Nowadays the NHS advises that healthy adults should have a pulse in the range of 60-100 beats a minutes so all these women seem healthy enough here. He also tested the pulses of lots of different people, young, old, fat, thin and even ‘Big-bellied’ or pregnant women. He compared pulse rates to patients’ temperature and in the different seasons and at different phases of the moon and published his conclusions in chart form. He was certainly thorough in his testing.

The watch was born from necessity for Sir John. He was a keen researcher and wanted to make accurate observations about his patients, so he had tried counting the pulse using the minute hand of a pendulum clock or a sea-minute glass, but neither of those things were portable so couldn’t be used at the patient’s bedside. Sir John needed a second hand on a pocket watch. He wasn’t the first person to invent a second hand on a watch, but his watch also had a stop mechanism making it a forerunner of modern stop watches. Sir John is credited with both being the first to want a second hand to time pulse rates and with popularising the practice among doctors of timing a pulse. His watches were made in 1695 by Coventry-born watch maker to King Charles II, Samuel Watson, and these were available to buy by the time Sir John’s book on the topic came out. The early ones weren’t entirely accurate and Sir John noted how he had to remember to keep testing his pulse-watch against his accurate pendulum clock and adding four or five seconds to his counting time to make an accurate minute.

Part of the Victorian bedside manner was to take the patient’s pulse for a full minute while gravely counting the seconds. Certainly, there are problems which are easily detected from the pulse, though these are cardiovascular. Today, the medic, or the assistant, slips a pulse oximeter onto your index finger to get a pulse reading. Gone are the days when the physician kept a watch in the pocket of his waistcoat.

I recently had a medic do my heart rate with a watch and counting, it was certainly a different experience to having the clip on my finger. I found it very interesting to see the difference in blood pressure measurements as well when they were done manually rather than on the machine.