Cake or Boiled Sparrow? by Amie Bolissian McRae

Last week newspaper headlines urged the over-65s to ‘Eat butter and cakes to keep … healthy’.[i] The president of the British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, concerned about malnourishment in older people, advocated fat-rich foods such as cream, butter, and sweet treats to prevent excessive weight loss in later life. Specific dietary advice to maintain health in old age, however, is by no means a recent concept. Sixteenth and seventeenth-century medical books contained emphatic guidelines for how much ‘the Aged’ should eat, what they should eat, and when they should eat it. Some of the advice would be compatible with modern English notions, such as ‘eat oftener and of smaller quantities’[ii] and avoid salt, but other suggestions are less recognisable, such as prescribing tobacco or boiled ‘sparrowes’ as warming ‘restoratives’.[iii]

That there was such a wealth of dietetic advice available for ageing men and women in early modern England may seem surprising, given modern misconceptions that people only lived to around forty in this period. However, the life expectancy figures historians cite can be misleading. They are heavily influenced by very high infant and child mortality, and, in reality, if you managed to reach twenty years-of-age, despite the recurrent plagues, wars, and famines, there was a reasonable chance that you could live on to at least sixty.

The over-60s made up approximately twenty percent of the adult population in seventeenth-century England, and their health and comfort was a concern not only to themselves, but also to their loved ones and families.[iv] English communities steeped in biblical traditions and references were no doubt hoping fervently for their promised ‘threescore years and ten’, and they could turn to dietary advice in books, pamphlets, almanacs, traditional customs, or local healers, to try and improve their chances of a long and salubrious life.[v]

So were the pre-modern health-conscious urged to eat cakes, butter and fried foods to fatten themselves up? Possibly by their loved ones and healers, but very rarely by the published medical texts. The most common advice was for those in ‘olde age’ to eat ‘sparingly’, especially in the evening.[vi] Thin broths and small, easily-digested meals were usually recommended, while a gradual wasting of the body with age was thought natural. In fact, it was proposed that ‘olde’ bodies could cope with ‘fasting’ far better than younger folk.[vii] Sweet foods were sanctioned, such as reviving cordials, but by far the most frequently encountered recommendations were for honey and wine.

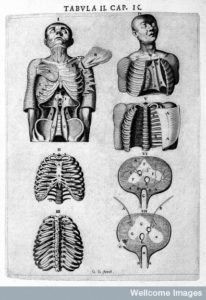

According to the humoural medical theory of the time, it was believed that the body grew colder and drier as it aged, the spirits and the heart grew weak, and unwanted putrid humours like corrupted phlegm clogged up the brain and other parts, causing decay and disease. Digestion was compromised, natural inner heat diminished, and the organs and skin started to desiccate and constrict. This meant that foods that were believed to have warming and emollient properties were considered particularly healthy and rejuvenating for ‘olde folkes’. Honey, following Galenic-Hippocratic and Arabic theory, was believed to be heating and moistening and was promoted in all forms, with mead and oxymel (a mixture of honey and vinegar) steeped in warming spices and herbs, such as nutmeg, ginger, and fennel, often prescribed for older people who were already suffering from various infirmities.

Only wine surpassed honey as the number one healthy option for old people. Strong red wines created dangerous stoppages in the body, but warm, ‘yellowish’ vintages were so ubiquitously regarded as healthful for the ageing that wine was described as ‘Lac senum’ or ‘Olde men’s milke’.[viii] Wine was thought to not only warm ageing bodies, but also promote healthful sleep, and ‘cheereth their Old Age’.[ix] Unfortunately, wine was not a cheap drink in England at this time and was considerably more expensive than ale or mead, meaning the wealthier minority of English society would have been far more likely to afford to indulge in this piece of dietary advice. Still, the poor could always console themselves with a nice boiled sparrow and some honey.

Amie Bolissian McRae is a Wellcome-funded doctoral researcher at the University of Reading, specialising in medicine and emotions in early modern England. Her PhD study, The Aged Patient in Early Modern England, investigates medical understandings and treatments of disease in old age, and explores the personal experiences and feelings of older patients, and those that cared for them, in England, c.1570-1730.

_________________________________________

[i] https://www.express.co.uk/life-style/health/1026693/diet-news-over-65s-cakes-butter-bacon-olive-oil

[ii] Leonardus Lessius, Hygiasticon: Or, the Right Course of Preserving Life and Health Unto Extream Old Age, (Series Hygiasticon: Or, the Right Course of Preserving Life and Health Unto Extream Old Age, 1634), p.81.

[iii] James Primrose, Popular Errours. Or the Errours of the People in Physick, (Series Popular Errours. Or the Errours of the People in Physick, 1651), p.332; Thomas Cogan, The Haven of Health, (Series The Haven of Health, 1636), Primrose, Popular Errours, p.156.

[iv] Demographic information: E. A.; Schofield Wrigley, Roger S., The Population History of England, 1541-1871: A Reconstruction (Cambridge: Cambridge Univeristy Press, 1989), pp.215-19

[v] Bible, KJV, Psalm 90:10.

[vi] Joannes Jonstonus, The Idea of Practical Physick, (Series The Idea of Practical Physick, 1657), p.27.

[vii] Thomas Elyot, The Castell of Helth, Corrected, (Series The Castell of Helth, Corrected, 1595), p.83

[viii] Lazare Riviére, The Universal Body of Physick in Five Books (London, 1657), p.235; Ibid.

[ix] A.B., The Sick-Mans Rare Jewel, (Series The Sick-Mans Rare Jewel; 1674), p.102.