A guest post by Olivia Smith

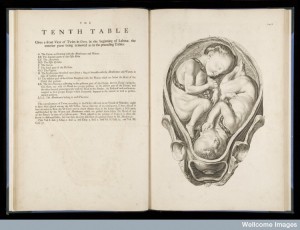

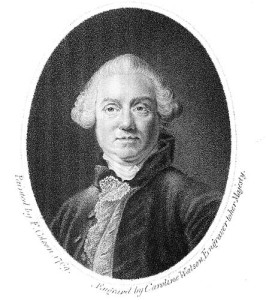

Anthony Ashley Cooper’s case notes tell how, on the afternoon of 12 June 1668, his abscess was ‘opened’, following which a ‘large quantity of prurulent [sic] matter, many bags & skins came away’.[1] The process of opening (v.) is both recorded and performed by the text which accounts for both the putrid matter that came out of the first Earl of Shaftesbury and also for the makeshift objects inserted in the opening (n.).

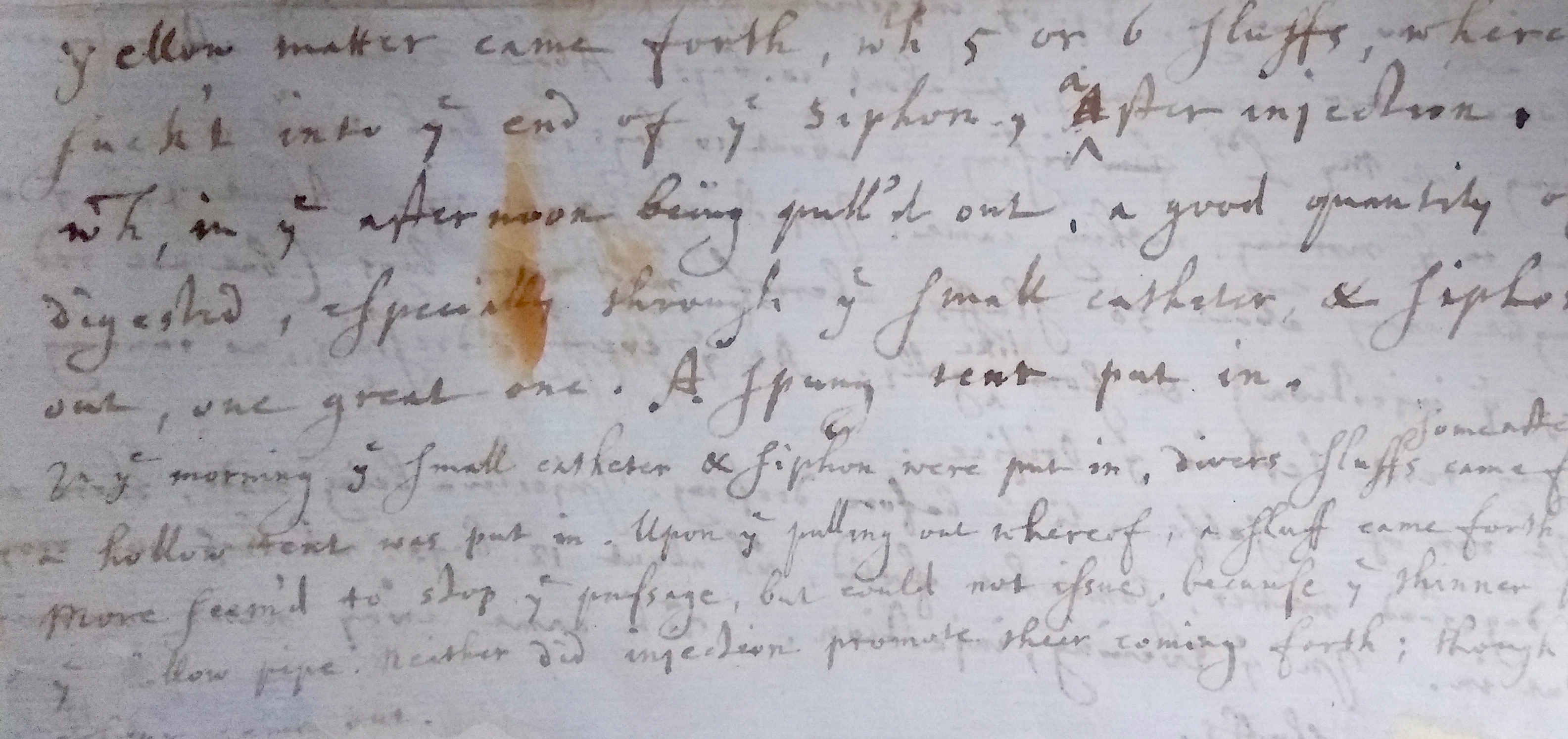

The document records how ‘[o]n Tuesday morning a great quantity of matter came forth, wth many bags, to ye number of at least 80’. That afternoon and on Wednesday the emissions slowed, but ‘On Thursday morning we had a new flux, both of matter and skins’. On Friday ‘a wax candle [of 4 ¾ inches] was put deepe into ye abscesse: & after ye drawing it out, some matter & divers sluffs succeeded’. ‘On Saturday morning drawing out ye candle nothing & evening some matter followed, & about 10 bags’.[2] Each subsequent day a similar entry was made, and on the sixth of July the notes show that a ‘small catheter & siphon were put in’ but were blocked by several more ‘sluffs’.[3] On the seventh ‘more yellow matter run in ye night’, and on the ninth this was joined by ‘a considerable quantity of yellow atheromatous matter’.[4] This word, made from the Greek root athare, insinuated ‘matter resembling oatmeal-gruel or curds’(OED).

Physicians working on Ashley’s case solicited accounts of analogous openings. Thomas Strickland sent an account from an associate in York:

a poor neighbor of mine fell into a great languishing with a great paine in his side and stomack, which continewed for a year or 2, and when nothing but death was expeckted by the Neighbourhood, a great swelling rise in his side, with infinit torment, which paine, made him send for a neighbor who had a penknife, that poor villaige not affording, a better instrument, or a person more skillfull for incision […] in short they cut him, upon the head of the sweling, immediately theire caime owt severall blethers (att the first cutting) like winde egs ^some^ as big as turky egs others as hen egs [5]

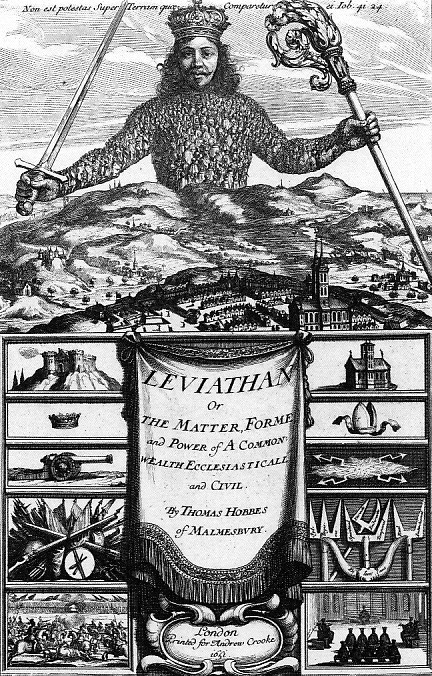

The picture on the frontispiece of Hobbes’ Leviathan, published in 1651 was already iconic. In it we see the figure of an enormous sovereign, depicted from the waist up, towering over the land. Inside his torso, contained within the shape of his body, are a multitude of small figures, representing the shape and structure of the commonwealth. This pamphlet writer depicts Ashley as a wannabe Leviathan but instead of being filled with citizens he would be swollen with purulent – here dropsical – contents. Hobbes’s subtitle was The Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Eccelsiaticall and Civil and this pamphleteer conjures the potential images of Leviathan filled with toxic matter or oozing onto the hills and city below.

This incision ‘kept it selfe open’ for a year, mattering all the time, until the patient was ‘recovered to a perfect health’. In these accounts, as in other accounts of openings in case notes and published in the scientific journal Philosophical Transactions, attention is paid to the shape, size and number of the pathological material inside the patient. In the end, Ashley’s doctors found a novel solution: a permanent tap was inserted into his cavity through which he could periodically drain his abscess.

Political pamphleteers nicknamed him ‘tapski’, satirizing his supposed political and religious affinities with the Polish as well as his drainage pipe. His status as a Whig politician grew, and one publication of 1681 conjured this striking image:

It is not to be imagined how this little Grigg was transported with the thoughts of growing into a Leviathan he fancy’d himself the Picture before Hobb’s Commonwealth already, nay he stopt up his Tap (as I am told) on purpose that his Dropsy might swell him bigg enough for His Majesty…[6]

Dr Olivia Smith is Wellcome Trust Research Fellow in the English Faculty at Oxford. In 2017 she published Cognitive Confusions: Dreams, Delusions and Illusions in Early Modern Culture and is just finishing a book on John Locke (who assisted in Ashley’s operation and wrote many of the case notes).

______________________

[1] PRO 30/24/47/2, fol.1. ‘Purulent matter’ is matter resembling or containing pus, OED.

[2] PRO 30/24/47/2, fol.1. Wax candles were regularly used in medicine for the purpose of clearing passages, as shown in Thomas Willis’s Oxford Casebook, ed. Dewhurst (Oxford, 1981), 143.

[3] PRO 30/24/47/2, fol.1v.

[4] PRO 30/24/47/2, fol.2.

[5] PRO 30/24/47/2, fol.4. Wind-egg: ‘an imperfect or unproductive egg, esp. one with a soft shell, such as may be laid by hens and other domestic birds’; ‘Blathers’ are presumably bladders: ‘A membranous bag in the animal body’, both OED..

[6] Anon, A Modest Vindication of the Earl of S______y: In a Letter to a Friend Concerning His Being Elected King of Poland (London, 1681), 2.