Stories of monstrous birth were popular in early modern England. Lots of historians have analysed the materials produced about these children and shown that the meanings attached to them changed over time. In the sixteenth century people interpreted them as a portent or omen from God. In the seventeenth century people also viewed them as punishment for sexual (or less commonly other) sin, a wonder of natural, and a scientific curiosity.

Making a monster

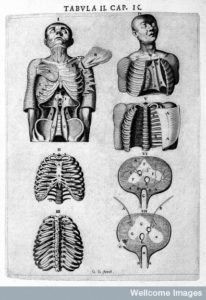

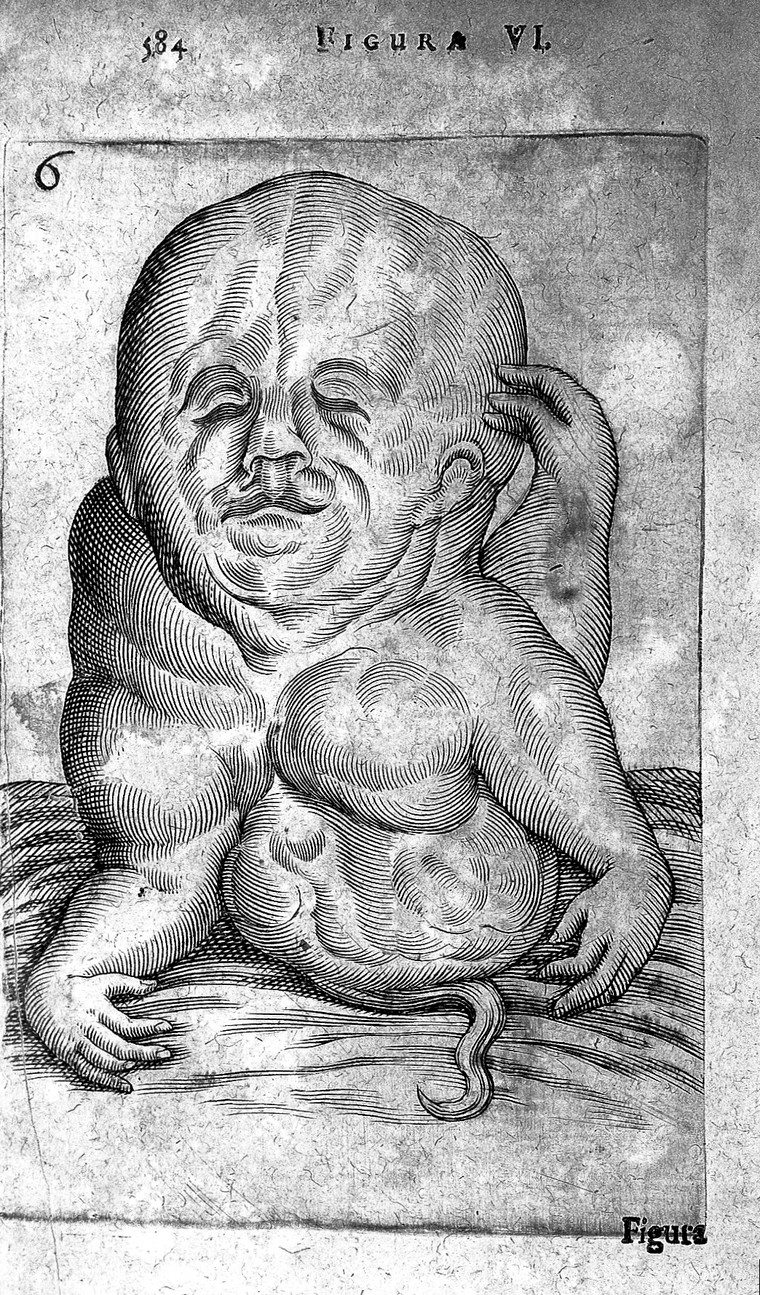

Monstrous births included a range of bodily conditions including conjoined twins and extra limbs. As you can see in these pictures some were more unusual and difficult to describe.

The popular text Aristoteles Masterpiece explained to readers that these births were the result of a variety of causes. Sudden frights or passions during pregnancy could affect the developing child, as could the influence of the stars. A mother with an overactive imagination might shape her child into the likeness of something she thought about. The author explained that some conditions were the result of too much or too little seed (seminal matter), the seed might be bad or corrupt and the mother’s womb might be too small. Sex and conception during menstruation also, supposedly, caused monstrous birth.

The monster of Kirkthorp

In the fifth edition of Medical Essays and Observations published by a Society in Edinburgh, Dr John Burton a physician in York recounted his observation of a monstrous child. The baby was the child of a ship’s carpenter and his wife who lived in Kirkthorp, near Wakefield in Yorkshire. Burton explained that the child was unusual because it had ‘no Parts of Generation proper either to [the] Male or Female’. There was, he said, no sign of these organs in ‘the Place where we should expect to find those Parts’.

Instead, there was a small spongy protuberance that resembled the tip of a penis just below the navel that was sore and tender. From many holes in this appendage the child urinated. This was apparently the only unusual element of the child’s anatomy. In every other way it was ‘made as is common’. In most monstrous birth stories the child died relatively soon after being born. However, Burton explained that this child lived until it was five years old and died from small pox, not its condition.

Burton did not regale his readers with details of the birth or the shock of those who witnessed it. This is different to many tales produced for a popular audience. One seventeenth-century author described a monstrous birth in Somerset as coming into the world after ‘a tedious Travel [labour]’. While the mother groaned, those attending her looking on the ‘frightful Apparition … amazed … knew not what to think, but long time stood doubtful in their wonder’. These women supposed the child more dreadful than it was but eventually realised that it was ‘a humain Creature’.

Despite not being as sensational as other accounts, Burton was keen to stress the truth of his story and claimed that many witnesses could corroborate what he had described. He concluded his tale there and didn’t describe how those around the Wright family interpreted or understood what they saw. Nonetheless, that he wrote in to the society shows that he expected others, particularly medical men, to find the birth as interesting as he had.

____________

Medical essays and observations, revised and published by a society in Edinburgh … (Volume 5) (Edinburgh 1742).

A True Relation of A Monstrous Female Child … near Taunton Dean (London, 1680).