UPDATE! THE BOOK IS NOW PUBLISHED! YAY! Available through all the usual channels.

As many regular readers will know along with Ciara Meehan I have been working hard finalising the proofs for an edited collection exploring Perceptions of Pregnancy from the Seventeenth to the Twentieth Century. We are very excited about the volume which looks at conception, contraception, pregnancy, and parenthood in life and literature. The volume will be the second output from the Perceptions of Pregnancy Researchers’ Network. A special edition of Women’s History was published in the summer of 2016 and includes a range of short article about pregnancy, maternity clothes and fatherhood.

If you are interested you can find more information and pre-order the book here.

Finishing the proofs got me thinking about all the blog posts I had written for about childbirth and pregnancy. So I thought I would see what the 5 most popular posts related to this theme have been.

5) Scraping into the top five is Ashleigh Blackwood’s illuminating post on the development m aternity clothes. Ashleigh revealed that the challenges of ‘dressing a bump’ are nothing new. Early modern women had to adapt their existing clothing as they became ‘prodigeous big’, letting out their stays and adding extra panels to their garments. Not everyone though was eager to accommodate a growing waistline and some women attempted to use their clothes to conceal their pregnancy for as long as possible. This did not always work as Elisabeth Charlotte, Duchesse D’Oleans noted wearing a particularly type of dress designed to conceal pregnancy could signal loudly to all around that the wearer was in fact pregnant.

aternity clothes. Ashleigh revealed that the challenges of ‘dressing a bump’ are nothing new. Early modern women had to adapt their existing clothing as they became ‘prodigeous big’, letting out their stays and adding extra panels to their garments. Not everyone though was eager to accommodate a growing waistline and some women attempted to use their clothes to conceal their pregnancy for as long as possible. This did not always work as Elisabeth Charlotte, Duchesse D’Oleans noted wearing a particularly type of dress designed to conceal pregnancy could signal loudly to all around that the wearer was in fact pregnant.

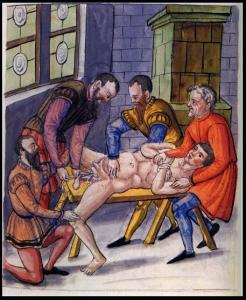

4) Making it safely onto the list is my recent post about the occupational health of seventeenth century midwives. The postures they stood in for hours on end during labour were thought to cause back ache and other problems, while the potential for poisonous, sometimes pox-riddled, blood to fall upon their hands left them open to being ‘ inflam’d and ulcerated by the sharp corrosive Matter’ or worse contracting syphilis. Medical rhetoric from the era normally focused on women’s knowledge and skill (or their lack of it if written by certain disapproving male authors), rarely does it mention the physical strength and dexterity that would have been required.

3) In third place is Victoria Sparey’s post about maternal identity and breast milk in Shakespeare’s plays. She shows that milk-orientated imagery is rife in the bard’s plays and that this in part is to do with the ways in which early modern audience’s understood that milk shaped the physicality and mentality of the suckling child. As the writer of a sixteenth century midwifery text Thomas Raynalde observed, ‘affections and qualities [of the nurse] passeth forth through the milke into the child, making the child of like condition and manners.’ Therefore in Shakespeare’s plays breast milk could powerfully connect nurses and mothers to the children they fed.

3) In third place is Victoria Sparey’s post about maternal identity and breast milk in Shakespeare’s plays. She shows that milk-orientated imagery is rife in the bard’s plays and that this in part is to do with the ways in which early modern audience’s understood that milk shaped the physicality and mentality of the suckling child. As the writer of a sixteenth century midwifery text Thomas Raynalde observed, ‘affections and qualities [of the nurse] passeth forth through the milke into the child, making the child of like condition and manners.’ Therefore in Shakespeare’s plays breast milk could powerfully connect nurses and mothers to the children they fed.

2) Coming in a close second place is Sara Read’s explanation of why prostitutes were thought to rarely get pregnant. There slippery wombs, made that way by excessive sexual activity, were unable to hold onto a conception. Sara shows that in erotic literature this trope was mostly played upon in terms of the potential for a baby to hinder a working woman’s trade. However, occasionally the trope was inverted when a client wanted to have a baby with his harlot. In one such case The London Jilt (1683) the protagonist Cornelia has to fake a pregnancy to retain her lover’s affections.

1) The most popular is …………. (insert drumroll) …….. Chris Langley’s discussion of birth, midwifery and infanticide in early modern Scotland. In this post Chris took us into the world of the Church courts and the efforts taken to identify whether a child had been still-born or whether a mother had committed infanticide. The post revealed that midwives were called upon to examine closely the bodies of these children to decide whether they had been fully formed and developed at birth. In one case Local midwife Janet Henrison visited the child a little after the birth, ‘and sawe ye bairne that it hade soft naills lyke other bairnes bot … [it] lookit not up whereby she thought the bairne was not borne to the full tyme’.