Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

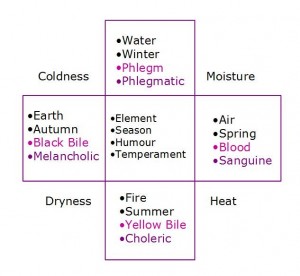

In the next part of our occasional series on early modern therapeutics, this week’s post looks at phlebotomy or bloodletting. As we’ve discussed before, blood was one of the four main bodily humours and early modern people saw keeping their blood levels stable as one of the most important ways of maintaining health.

Bloodletting was a process of draining blood from a vein by means of a specially designed knife and a small bowl to receive the blood.

Credit: Science Museum, London. Wellcome Images

It might seem a little extreme to us from a modern perspective but it was an extremely popular treatment in the early modern period, one which people sought out. Indeed bloodletting was so ingrained to people’s thinking that James I was able to use it in metaphor in his address to Parliament in 1610. James explained that the role of the king was like a paternal figure for the nation because this was the natural order of things. And just as the head of a body ‘hath the power of directing all the members of that body to that use which the judgement of the head thinks most convenient’ so too has the king the duty to care for his subjects. This care might include unpopular policies and decisions, or metaphorically, treatments such as ‘sharp cures or cut off corrupt members, let blood in what proportion it thinks fit and as the body may spare.’1

Sometimes the prescribing physician would carry out the bloodletting himself, but he would also often refer the patient to an apothecary or barber-surgeon for the treatment. The site on the body where the blood was taken from was dependant on the disease being treated. Men and women both were let blood for all manner of illnesses, from places including the tongue, arm, and leg. However, women’s assumed inability to burn off excess humours through an active lifestyle and warmer body meant that they had addition cause for phlebotomy if they had menstrual problems.

The diaries of many early modern people note when they have been let blood. Gentleman Nicholas Blundell (c1669-1737) of Little Crosby is no exception. Blundell made a note of when he, his wife and daughter were let blood, and by whom. The diary for the years 1702-28 cover his wife’s main childbearing years and so is a useful text to consult to show one family putting the therapeutic treatment into practice.2 Blundell was married on 17 June 1703 to Frances, the daughter of Marmaduke, the second Lord Langdale. On 23 January the diary records that ‘My Wife sent for Dr. Fabius, he said she was with child’.3 This is a remarkable entry because their first child was born exactly nine months later, on 22 Sept 1704, so even allowing for an overdue birth, this makes the diagnosis very early by early modern standards. Normally a pregnancy wasn’t confirmed until the baby ‘quickened’ or was felt to move in the womb. The daughter was named Mary after Blundell’s mother. Two years later a second daughter Frances was born, on 25 Sept 1706.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

The two daughters were the only children of the marriage, but the fact that the couple would have liked a larger family is indicated by the treatments including bloodletting that Frances underwent. On 23 June 1708 ‘Mrs Bootle blodyed my wife’.4 It might be the case that this treatment was advised my Dr Fabius, as the previous entry records that Blundell sent the doctor a present of ’22 Adders’ which may have been in lieu of payment. Both of the Blundells consult Mrs Bootle who lived in Peele on a number of occasions. A month after being let blood later Frances went drink spa water at Wigan.5 The next mention of Frances being let blood is on 1 May 1709 when ‘Duke Bluddyed my Wife, Nich: Johnson Wm Gray, I &c were present’.6 When she is let blood again on 30 March 1711, Blundell noted that ‘Rich: Cartwrit let my Wife blood in ye Foot’.7 This indicates that Frances might have been having problems with her menstrual cycle as the recommended treatment for bringing on a period was to let blood from the ankle. This had been the standard treatment from the time of Galen.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

However the opening of a wound to leg blood was clearly not a risk free treatment as Frances’ next visit to Mrs Bootle ‘to shew her a Soar place she has in her Legg’.8 This sore seems to have become a persistent complaint as the next year Blundell recorded that his wife had once again consulted Mrs Bootle on 23 May 1712 to show her foot that ‘was soar from being Bluddied’, and another year later (13 June 1713) she consulted a Mrs Maginis about the same problem.9 Indeed as late as 1725 the Blundells were consulting people about Frances’ sore leg.10

This injury didn’t put the Blundells off bloodletting and he himself records several occasions when he is let blood for all manner of ailments, including having a sore side after a coaching accident. Most tellingly in April 1724 the 19-year-old Mary, known as Mally, is let blood for an unspecified illness.11 Clearly the benefits were thought to outweigh the risks.

__________

1. James I speech to Parliament, 21 March 1610.

2. Nicholas Blundell, Blundell’s Diary – Comprising Selections from the Diary of Nicholas Blundell, Esq. from 1702-1728, ed. by Rev T. Ellison Gibson (Liverpool: Gilbert G. Walmsley, 1895).

3. Ibid. p. 19.

4. Ibid. p. 62.

5. In the eighteenth-century Wigan’s reputation as a spa town grew, and it even styled itself as the New Harrogate. Its waters were eventually polluted by the coal mining for which the town is most usually associated. See http://www.wingedwheels.info/WiganTownTrail.pdf

6. Blundell’s Diary, p. 74.

7. Ibid. p. 90.

8. Ibid. p. 93.

9. Ibid. p. 102 and 115.

10. Ibid. p. 208.

11. Ibid. p. 200.

© Copyright Sara Read, all rights reserved.

Long ago, I gave a paper at the Liverpool Medical History Society in which I discussed the wide range of medical practitioners whom the Blundells consulted, in Liverpool and elsewhere, and suggested reasons for their choices. I was vigorously attacked by doctors in the audience, as a vile advocate of quack “alternative” medicine.

Oh dear David, you’d have thought they’d have found the topic interesting.