Many of us avoid going to the doctor and it is an often repeated stereotype that men in particular won’t get help for their illnesses unless absolutely necessary. But why is this? For some it is the worry that going to see a doctor will involve exposing the naked body to the gaze of a medical professional. Early modern men and women, it would appear, were no different. So in this post I am asking how did men feel about consulting a medical practitioner for a sexual health problem in the early modern period, knowing that this might mean exposing their genitalia to others?

Nakedness in the early modern period was a rare occurrence with men and women only being truly naked at birth and death. Sarah Toulalan has shown that even during intimate moments couples were rarely completely undressed. Seventeenth-century erotic literature shows images of men and women with their clothes is a state of disarray rather than completely removed.i Nakedness was also typically loaded with negative connotations. Particularly in the seventeenth century nakedness was associated with dangerous religious radicals who indulged in illicit sexual practices. Given the way men and women understood nakedness how did early modern patients respond to the necessity to remove their clothes either fully or partially? More importantly, can we suppose that a patient whose torso remained clothed felt little shame because his clothing was only disordered?

Scholars of medical history have often noted that patients were not required to remove their clothing during an initial consultation with a physici an. (As can be seen in the image below) Instead physicians would rely upon the patient explaining their symptoms, would take the pulse and would perhaps examine a flask of urine to make a diagnosis. Historians discussing this issue have often focused on the treatment of women by male practitioners. Early modern society prized female modest and chastity, and was cautious about the access that men should have, even during a medical consultation, to the female sexed body. This concern was voiced by those who, in the 1670s, criticised ‘groaping’ doctors, men who claimed that they could not assess women’s menstrual complaints without viewing and touching their reproductive organs.ii Some man-midwives had also developed dubious reputations connected to immodest sexual behaviour, not all of which were unfounded.iii

an. (As can be seen in the image below) Instead physicians would rely upon the patient explaining their symptoms, would take the pulse and would perhaps examine a flask of urine to make a diagnosis. Historians discussing this issue have often focused on the treatment of women by male practitioners. Early modern society prized female modest and chastity, and was cautious about the access that men should have, even during a medical consultation, to the female sexed body. This concern was voiced by those who, in the 1670s, criticised ‘groaping’ doctors, men who claimed that they could not assess women’s menstrual complaints without viewing and touching their reproductive organs.ii Some man-midwives had also developed dubious reputations connected to immodest sexual behaviour, not all of which were unfounded.iii

However, scholars are yet to fully consider these same issues for men. It would seem that men were not explicitly concerned about the potential for illicit or unsolicited sexual contact with medical practitioners. Yet the removing of clothes could potentially have been shameful, particularly when the disorder required the exposure of the genitals. Treatises produced by seventeenth-century surgeons suggest that they did indeed view the affected part of the body as a part of diagnosis, even in cases of sexual health problems. To diagnose a hydrocele, a watery swelling of the testicles, the Scottish surgeon Peter Lowe wrote that amongst several signs, including heaviness and a lack of pain, it ‘is knowne beholding the Cod betweene your eye and the candle’.iv

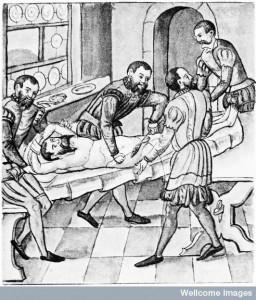

In addition to the exposure of their bodies during the diagnosis, patients could also be required to be unclothed during operations, particularly those to remove hernias. In this situation however, men, may have felt more shame. At this point it would have been established that the male patient had a disorder affecting his reproductive organs. Sexual health problems had the potential to damage manliness. As Anthony Fletcher and Alexandra Shepard have described, manhood in early modern England required men to display vigorous virility; men needed to be potent and able to produce children.v Many medical texts discussed the appropriate number and form of testicles a man required to be potent: In The Anatomy of the Body of Man (1653) Johann Vesling reassured his readers that ‘the Divine Creator hath formed two of them, that so the work might be done by the other when the one languisheth, or is deficient.’vi Thus a hernia that damaged, or resulted in the removal of, a testicle could threaten manliness and manhood. In addition to this shame, the male patient then had to expose his damaged genitalia to an audience. As one treatise suggested hernia surgery required the patient to be partially ‘naked’ in front of the surgeon and at least one assistant: ‘to which purpose the Patient is to be laid upon his Back, with his Buttocks somewhat high; then the Skin being grip’d a-cross the Tumour, the Surgeon holds it on one side, and the Assistant on the other, till he makes an Incision, following the Folds or Wrinkles of the Groin’.vii

However, as this image of hernia surgery from 1559 shows, there could be considerably  more people present and the patient could be required to be completely naked. It is not made explicit in any of the texts I have read that men felt shame about this process. We can perhaps only speculate on how they felt and whether they were ashamed of their vulnerable nakedness. Some case histories recorded by surgeons suggest that men were very lax about seeking treatment for disorders that affected their reproductive organs, including hernias, which could have severe consequences: one surgeon recalled that,

more people present and the patient could be required to be completely naked. It is not made explicit in any of the texts I have read that men felt shame about this process. We can perhaps only speculate on how they felt and whether they were ashamed of their vulnerable nakedness. Some case histories recorded by surgeons suggest that men were very lax about seeking treatment for disorders that affected their reproductive organs, including hernias, which could have severe consequences: one surgeon recalled that,

‘a certain Gentleman named Daniel de Chalou, who for several Years had been afflicted with an Enterocele, chanced to use some violent Exercise, upon which the Gut fell into the Scrotum, whence came great pain in his Belly, continual Vomiting, great Restlesses, and a Retention of the Urine and Excrements. Having neglected to take any care for remedying this, all the Symptoms encreased, by reason of the violent pain in the Belly’.viii

One possible reason for this neglect was the patient’s concern about exposing his genitalia to other men, even a surgeon. Although we cannot be sure from notes such as this one, as this project continues it will hopefully be possible to make some more confident assertions about how men felt about consulting a medical practitioner with a sexual health problem and how they felt about the necessity of removing their clothes in order to be treated.

i Sarah Toulalan, Imagining Sex: Pornography and Bodies in Seventeenth-century England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), P. 233.

ii Patricia Crawford, Blood, Bodies and Families in Early Modern England (Harlow: Pearson Education Limited, 2004), p. 34.

iii Hilary Marland, The Art of Midwifery: Early Modern Midwives in Europe (London: Routledge, 1993), p. 39.

iv Peter Lowe, A Discourse of the whole art of Chyrurgerie: Wherein is exactly set downe the Definition, Causes, Accidents, Prognostications, and Cures of all sort of Diseases both in generall and particular, which at any time heretofore have beene practised by any Chyrurgion … 3rd Edition corrected and much amended (London, 1634), 252

v Alexandra Shepard, Meanings of Manhood in Early Modern England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003); Anthony Fletcher, ‘Manhood, the Male Body, Courtship and the Household in Early Modern England’, History, 84/275, (1999), 419-36

vi Johann Vesling, The Anatomy of the Body of Man: Wherein is Exactly Described Every Part Thereof in the Same Manner as it is Commonly Shewed in Public Anatomies…Translated by Nicholas Culpeper (London, 1677), p. 23.

vii M. le Cler, The Compleat Surgeon: Or, The Whole Art of Surgery explain’d in a most familiar Method. Containing An exact Account of its Principles and Several Parts … Written in French by M. le Cler, Physician in Ordinary, and Privy-Counsellor to the French King; and faithfully translated into English. (London, 1696), p. 236.

viii M. de La Vauguion, A Compleat Body of Chirurgical Operations, Containing The Whole Practice of Surgery. With Observations and Remarks on Each Case. Amongst which are inserted, the several ways of Delivering Women in Natural and Unnatural Labours (London, 1699), p. 44.

© Copyright Jennifer Evans. All rights reserved.

A hernia occurs when an organ or fatty tissue squeezes through a weak spot in a surrounding muscle or connective tissue called fascia. The most common types of hernia are inguinal (inner groin), incisional (resulting from an incision), femoral (outer groin), umbilical (belly button), and hiatal (upper stomach).`..^^