Guest post by Elisabeth Brander

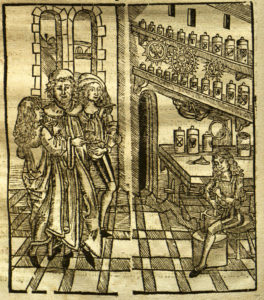

Antibiotic ointments, fungal creams, and soothing lotions are frequently found in modern medicine cabinets. These kinds of treatments were also a staple of early modern medicine. During the early modern period, the most common types of topical remedies were oils, ointments (unguents), and plasters (sometimes used interchangeably with cerats).

The key distinction between these different preparations was their consistency. Oils were the thinnest and still in a liquid state. Ointments were firmer, but still soft and spreadable. Plasters/cerats were the hardest, stickiest substances of all. Regardless of consistency, all of them were formulated with herbs, flowers, animal parts, and/or minerals (sometimes poisonous ones!) that provided the desired medicinal effect.

Oils were the most straightforward category. They were made either by expression, infusion, or by applying heat. There are numerous extant recipes for infused oils, which would have been easy to make at home. For example, the instructions given by the Scottish surgeon Peter Lowe for oil of anetide (dill) were straightforward and required no special equipment: macerate the herb in sweet oil and let it sit in the sun for five or six days (or boil it in a double vessel), then strain it. This simple remedy had the virtue to “heat, digest, and assuage the pain of the head, sinews, and procure sleep.”[1]

Both ointments and liniments used a base of wax, rosin, axungia (soft animal fat), mucilage (a gelatinous plant substance), turpentine, and/or butter to give them a thicker, spreadable texture. The difference between the two lay in the proportion and type of ingredients used. In his herbal Botanologia, the English empiricist William Salmon argued that liniments were essentially soft ointments simply made without wax – wax was therefore the distinguishing factor.[2]

This was a straightforward distinction in most cases, but not always. Ambroise Paré, one of the period’s most prominent barber surgeons, noted that, “there be some unguents which admit not any wax to be added, as Aegyptiacum, and all such as are used in gangrenes, and all sorts of putrid ulcers; because to these kinds of diseases all fatty things, as oils, fats, rosins, and wax, are enemies. Therefore we substitute in the place of them in Aegyptiacum, honey and verdigrease; for of these it hath his consistence, and his quality of cleaning.”[3]

The firmest topical remedies were cerats and emplasters. Like ointments and liniments, the difference between the two came down to the ingredients used. According to Paré, “The proper matter of Cerats is new Wax and Oils… Cerats which are made with Rosins, Gums, and Metals, do rather deserve the names of Emplasters than Cerats…An Emplaster is a composition which is made up of all kind of Medicins, especially of fat and dry things, agreeing in one gross, viscous, solid, and hard body, sticking to the fingers.” Salmon defined emplasters as substances made with a base of olive oil or lard combined with either beeswax, gum, or even (toxic) mineral powders such as red and white lead. Cerats, on the other hand, were “soft emplasters, which will spread without melting in a Pan, or the help of Fire; being for the most part made with Oil Olive, and in a much larger quantity.”[4]

Different consistencies meant different uses. Ointments and liniments could be easily spread onto the arms, legs, or torso; however, when the afflicted body part was crooked and narrow, like the inner passage of the ear, an oil-based liquid remedy was a better option. Furthermore, Paré drew a correlation between consistency and efficacy. He believed that while oils and liniments were fairly mild therapies, ointments were more forceful and could “overcome the contumacy of a stubborn evil by their firm and close sticking to.”[5] Plasters were even more potent: “We use Plasters when we would have the remedy stick longer and firmer to the part, and would not have the strength of the Medicament to flie away or exhale too suddenly.”[6]

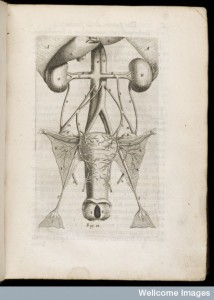

These remedies had a variety of different uses. Cerats and emplasters could be spread on a wound or an ulcer to keep them clean, or even used to treat skin cancers by causing tissue to die and slough off in what is known as an eschar. Ointments and liniments could be spread onto sore limbs and joints to relieve pain and inflammation, or to help treat minor wounds. Oils could also be rubbed directly onto the body, or put on cloths that were used as compresses.

Elisabeth Brander is the rare book librarian at the Bernard Becker Medical Library in St. Louis, Missouri. She enjoys the sense of wonder that working with rare books brings her. While her research interests vary, perennial favorites include the evolution of anatomical illustration, the development of print culture, and the connection between food and medicine.

__________________________

[1] Peter Lowe, A Discourse on the Whole Art of Chyrurgerie, 3rd edition (London: Printed by Thomas Purfoot, 1634): 441.

[2] William Salmon, Botanologia: The English Herbal or History of Plants (London: Printed for H. Rhodes & I. Taylor, 1710): xvi.

[3] Ambroise Paré, The Works of that Famous Chirurgeon Ambrose Parey, Translated out of Latin, and compared with the French, by Th. Johnson (London: Printed by Mary Clark, 1678): 645.

[4] Salmon, xvi.

[5] Paré, 647.

[6] Paré, 649.