Much of my research is focused on infertility and the problems early modern men and women had trying to have children. But alongside barrenness, impotence, and unfruitfulness, early modern medical literature also expressed concerns that people could be exceptionally or super-fertile. In some early modern diaries there is evidence that people were concerned by their ability to bear lots of children, particularly when the number of children in the family became a financial burden. In 1667 after the birth of her eight child Alice Thornton, on finding herself pregnant again, wrote ‘if it had been good in the eyes of my God, I should much rather … not to have been in this condition.’1

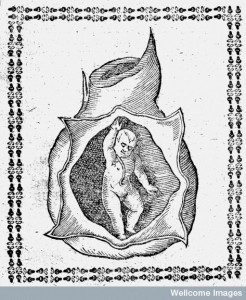

Yet the discussions in some medical literature go beyond the idea that a couple might have numerous children over the course of their child-bearing years. Rather they look at the apparent ability for woman to conceive and carry many foetuses at once. In part the idea that a woman could carry multiple children came from a theory that was being discussed, critiqued and slowly rejected across the period. This was that the womb was made up of seven segments and so a woman could carry seven children at one time – 3 girls (on the left), 3 boys (on the right) and 1 hermaphrodite (in the middle).

Yet the discussions in some medical literature go beyond the idea that a couple might have numerous children over the course of their child-bearing years. Rather they look at the apparent ability for woman to conceive and carry many foetuses at once. In part the idea that a woman could carry multiple children came from a theory that was being discussed, critiqued and slowly rejected across the period. This was that the womb was made up of seven segments and so a woman could carry seven children at one time – 3 girls (on the left), 3 boys (on the right) and 1 hermaphrodite (in the middle).

Jane sharp (1671) for example, told her readers that it had been ‘much and long disputed’ how many ‘cells’ were in the womb, ‘Mundinus and Galen say there are seven several Cells, and that a woman may, by reason of so many places distinct one from the other, have seven Children at a birth, and many midwives are of this opinion, but none that ever saw the womb can think so.’ Clearly, Sharp herself did not put much stock in this assumption, but she did imply that many other midwives thought that this was the case.

Sharp went on to tell her readers that ‘others say a woman can have but two Children at once because nature hath given her but two breasts’. She didn’t believe this either, arguing that a woman couldn’t only walk two miles because she had two legs and that it was not unusual for a woman to have triplets. To a modern reader these concerns do not necessarily seem to be about ‘exceptional’ fertility; we are aware that women can have sextuplets, septuplets and octuplets. But Sharp went on to say that ‘Aristotle tells us of one woman, that at four births brought forth twenty perfect living Children’. This is a great number, but not the most extreme example found in the medical literature.2

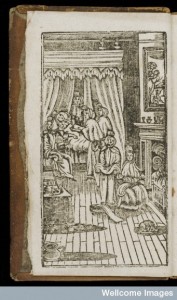

Ambrose Paré’s surgical treatise devoted a whole chapter to discussing ‘Of women bringing many children at one birth’. His chapter culminated in two stories: the first about the wife of a Polish Count who had thirty five live children on the 20th January 1296; and the second about an Italian woman named Dorothy who bore twenty children in two births (9 in the first and 11 in the second). He included this picture of her and stated that ‘she was so bigge, that she was forced to beare up her belly, which lay upon her knees, with a broad and large scarfe tyed about her necke.’ 3

Ambrose Paré’s surgical treatise devoted a whole chapter to discussing ‘Of women bringing many children at one birth’. His chapter culminated in two stories: the first about the wife of a Polish Count who had thirty five live children on the 20th January 1296; and the second about an Italian woman named Dorothy who bore twenty children in two births (9 in the first and 11 in the second). He included this picture of her and stated that ‘she was so bigge, that she was forced to beare up her belly, which lay upon her knees, with a broad and large scarfe tyed about her necke.’ 3

It was not only medical treatises that picked up on the concern over the potential for women to have numerous children at once, at least one early modern ballad also played upon the theme of barrenness and super-fecundity. Ballads were cheap printed song sheets often decorated with woodcut images and they give us some insight into the popular ideas of the period.

The Lamenting Lady told the story of a barren woman who grew jealous when she saw ‘beggers borne of low degree’ with many children. One day a beggar with ‘two sweet children in her armes’ came to the lady’s door and asked for help. Instead of offering assistance to the beggar-woman, the lady taunted her that she was a harlot: ‘Thou art some Strumpet sure I know/ and spend’st thy dayes in shame,/ And stained sure thy marriage bed/ with spots of black defame’. As a punishment for her uncharitable and ungodly behaviour the lady grew ill and her womb swelled so big that it appeared strange and monstrous. She then ‘delivered forth in feare/ As many children at one time/ as daies were in the yeare:/ In bignesse all like new bred mice’.

The Lamenting Lady told the story of a barren woman who grew jealous when she saw ‘beggers borne of low degree’ with many children. One day a beggar with ‘two sweet children in her armes’ came to the lady’s door and asked for help. Instead of offering assistance to the beggar-woman, the lady taunted her that she was a harlot: ‘Thou art some Strumpet sure I know/ and spend’st thy dayes in shame,/ And stained sure thy marriage bed/ with spots of black defame’. As a punishment for her uncharitable and ungodly behaviour the lady grew ill and her womb swelled so big that it appeared strange and monstrous. She then ‘delivered forth in feare/ As many children at one time/ as daies were in the yeare:/ In bignesse all like new bred mice’.

This idea that it was possibly for a woman to bear 365 small children in one labour (all of which subsequently died) was likely sensationalised in order to appear as a punishment from God.4 Nonetheless, it is evident that early modern medical writers and the wider populace were not clear about the limits and capacity of the womb, and were concerned that it was possible for women to conceive, carry and give birth to large numbers of children at one time.

__________________

1. Alan Macfarlane, Marriage and Love in England: Modes of Reproduction 1300-1840 (Oxford, 1986), p. 62.

2. Jane Sharp, The Midwives Book … (London, 1671), pp. 69-70.

3. Ambrose Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion … (London, 1634), p.971.

4. The Lamenting Lady… (1620?).

© Copyright Jennifer Evans all rights reserved.

Well spotted.

Consider the fecundity of rabbits, which can bear two litters at once. And Mary Tofts, at the same time.

Mary Toft is interesting because they very soon realise that she is faking the birth of ‘rabbits’- but it again plays on the idea that women could not just have abnormal but multiple births.

I have yet to figure out how many they thought was too many … although they do see to recognise that three or four at once (particularly in hotter countries where women are naturally more fertile) is okay.

Without looking at the texts, I would guess that such women would be hot and wet — sanguine — unlike the dominant English temperament of cold and wet — phlegmatic — for which tobacco was introduced as a remedy. Sadly, of course, this very hot and dry medication, when taken without medical supervision, could lead those of a melancholy constitution into the sad state of melancholia adusta — burnt melancholy.

Like that other new and dangerous medicinal substance, water, recreational tobacco was a sword in a madman’s hand.