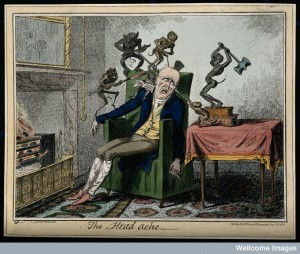

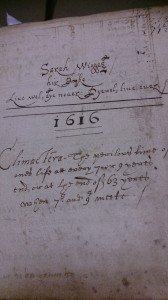

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Recently a friend asked me what early modern people did to combat migraines. From the seventeenth-century manuscript recipe books housed in the Wellcome Library it would appear that many early modern men and women afflicted with migraines, or ‘megrim’, favoured plasters and medicinal hats to relieve their pain.

Some of these plasters were relatively simple mixtures of herbs and ingredients spread over linen and applied to the forehead. One remedy in a book attributed to Elizabeth Okeover, for example, was made as follows,

‘take the juce of Betony & viniger with crums of browne bread make it into a plaster & lay to the forehead as hot as it can be endured: pro:’1

The final note here ‘pro’ is an abbreviation for probatum est (in Latin) or it is proven (in English), which suggests that at some point this remedy was made, used, and was believed to have had a beneficial effect.

Lady Ayscough’s recipe book dated to 1692 recommended making a medicinal cap to combat migraines:

‘For ye Megrim or giddiness of ye Head, Take Betty sweet majoram rosemary of each one handful dry them to powder putt to it white frankincense mastic cloves nutmeggs cinnamon of each half a spoonful cast ye powder upon ye skarlett flocks carded quit them in taffaty saunett make a capp & weare itt.’2

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Other remedies mixed herbs, spices and animal parts that may not have been so pleasant when applied to the head. Mrs Corlyon’s book included a remedy made from a handfull of wild daisies mixed with a ‘dozen great earth wormes’, this was mixed with an egg white and spread upon a forehead sized piece of linen, taking care that it reached the eye brows and the temples.3 The patient was then required to lye on their back for an hour with the medicine bound to their head with a handkerchief.

Another recipe in a book attributed to Sir Thomas Osborn used the ox gall as one of its constituent parts,

‘For the Megrame, Take of dragons blood one dragme and a nutmegg powder them & with the white of an egg & gaule of an oxe of each a litle mingle [mix] them togeither, spread this uppon the innermost parte of the oxe gaule in manor of a plaister and aplie it to thy forehead & temple’.4

I’m not sure my friend will be rushing out to test the effects of earthworms and ox gall, but perhaps lying still for an hour or so with something soothing applied to the head might be of help.

______

1. Wellcome Library, London, Elizabeth Okeover (& others), MS.3712/100.

2. Wellcome Library, London, Lady Ayscough, MS.1026/62.

3. Wellcome Library London, Mrs Corlyon 1606, MS.213/5.

4. Wellcome Library, London, Sir Thomas Osborne (1631-1712), MS.3724/49. See also Wellcome Library, London, Bridget Hyde, MS.2990/94.

Have you considered this one? Also Mrs Corlyon, and requires quite a complicated bit of manoeuvring …

“One of the principall causes whence many of the paines of the Heade do proceede is the opening of the heade, the wch doth happen comounly by one of these three meanes viz. By ouer much moisture beyng about the Braine: By a sodaine iumpe or fall: Or by vehement ryding or such like. The best meanes to know when your head is open is this. Bow downe the end of your thombe, and if you cannot receaue the space that is betwixt the two ioyntes betweene your teethe, the vpper ioynte beyng towardes your vpper teethe, and the lower ioynte to your lower teethe then your head is opened: If by the paine you haue and by this experiment you do find your heade to be open: then do this. Leane your selfe vppon your elboes with your heade somewhat lowe ouer a table, putting your face betwixt your handes setting your thombes vnder the greatt skull Bone, that is behinde your eares, your fingers reaching vpp towardes the mould of your heade. Gather your face into your handes leaninge somewhat harde and squeasing your face and the temples of your heade togeather, lett your fyngers meete about your heade and this continue for the space of halfe an hower att a tyme … You shall knowe when your heade is closed by your thombe as is aforesaid. And as you doe thus to cloose your heade. annoynte your temples about the eares and the Noddell of your heade and so downe to the nape of your neck with the Oyntement of Lauander … ”

Mrs Corlyon, A Book of divers medecines, 1606

That would indeed take some manoeuvring – part remedy, part distraction tactic?