Before Christmas Paul Middleton looked at the role of unicorn horn in combatting the effects of poisons and venoms. Today’s post is on a similar theme and looks at one very particular type of venomous bite – the bite of a mad dog. Ambrose Paré explained dogs were particularly prone to madness:

‘DOgges become mad sooner than other creatures, because naturally they enjoy that temper and condition of humours which hath an easie inclination to that kinde of disease, and as it were a certaine disposition, because they feed upon carrion and corrupt, putride and stinking things, and lap water of the like condition; besides the trouble and vexation of losing their masters, makes them to runne every way, painfully searching and smelling to every thing, and neglecting their meat. A heating of the bloud ensues upon this paines, and by this heate it is turned into a melancholy, whence they become madde’1

In complete contrast, Paré continued that dogs went mad,

‘by occasion of cold, that is, by con|trary causes, for they fall into this disease not onely in the dog-daies, but also in the depth of winter. For dogges abound with melancholike humouts, to wit, cold and drie. But such humours as in the summer through excesse of heate, so in the depth of winter by constipation and the suppression of fuliginous excrements, they easilie turn into melancholie. Hence followes a very burning and continuall feaver, which causeth or bringeth with it a madnesse.’2

These mad dogges were easily recognisable they ‘hath sparkling and fierie eies, with a fixed looke, cruell and a squint, hee carries his head heavily, hanging downe towards the ground, and somewhat on one side, hee gapes, and thrusts forth his tongue, which is livide and blackish; and being short breathed, casts forth much filth at his nose, and much foaming matter at his mouth’.3

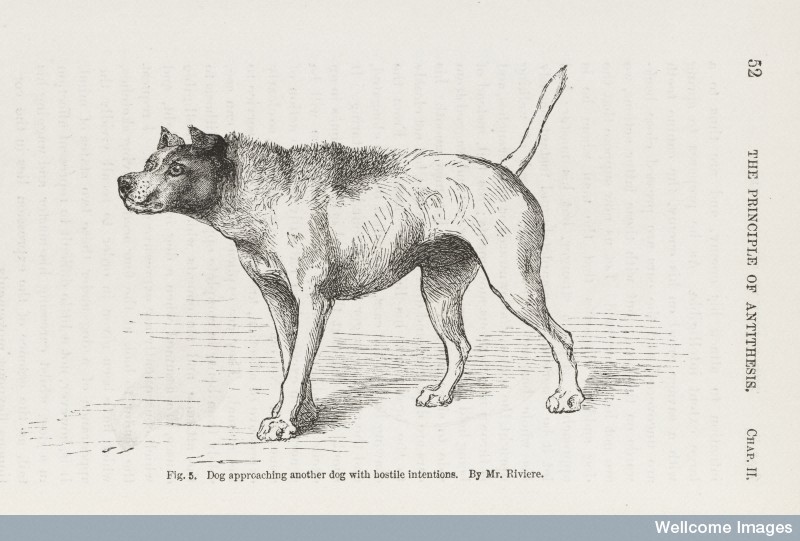

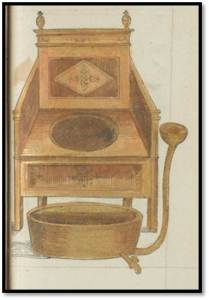

Bites from such animals were considered to be dangerous, however, Paré warned that it was not always easy to discern whether a man had been bitten by a mad dog because the wound causes no more pain that other wounds, and, unlike bites by other venomous creatures, did not swell.4 In order to establish definitively whether the bite was from a mad dog he suggested the following diagnostic test:

Credit: Wellcome Library, London

‘[put] a piece of bread into the quitture that comes from the wound. For if a hungry dog neglect, year more fly from it, and dare not so much as smell thereto, it is through to bee a certaine signe that the wound was inflicted by a madde dogge’.

Alternatively the bread could be fed to hens, who would presently die if the wound was infected.5 Paré dismissed this latter version of the test though, pointing out that it had failed when he had tried it. If these tests proved to be positive it did not bode well for the patient who was expected to suffer from the falling sickness (epilepsy) and eventually go mad themselves.6 Nicholas Culpeper’s School of Physick even suggest the expected timeline of this progression: ‘Observe this general rule, Creatures that are bitten with a mad Dog near the new Moon, fall mad at the full; and those that are bitten at full Moon, fall mad at the new.’7

It is perhaps little wonder then, given the severity of the outcome, that many recipe collectors included remedies for the bite of a mad dog in their recipe books:

This brief remedy from an anonymous seventeenth century collection suggested taking the blossoms of wild thistles, which had been drying in the shade, and beating them to a power to be drunk four times a day in white wine.

The recipe book attributed to Anne Brumwich suggested repeatedly applying a red-hot irons to the body as close a possible to the wound in order to draw the venom out of the wound, and cautioned that this would only work if done immediately after the patient had been bitten.

The recipe book of Johanna Saint John offered a slightly more complex recipe, which it was claimed never failed, containing rue, garlic, London treacle, pewter shavings and strong ale. The patient was to take 9 spoonful of this remedy were to be taken each day for approximately nine days, depending upon the age of the patient.

Another remedy in Elizabeth Godfrey’s book suggested placing walnuts, honey, onions and salt on the wound.8 Although each of these remedies was different, the prevalence of these cures in the recipe collections may suggest that this was an ailment people feared they would encounter and have to treat. It was, perhaps, the rather dire prognostications offered by writers such as Paré that encouraged men and women to seek out remedies of this kind and keep them on hand just in case they crossed paths with a dog ‘stumbling like one that is drunke’ who would ‘bites all he meets without any difference, not sparing his master, as who at this time hee knows not from a stranger or enemie.’9

For more on mad dogs and rabies please check out this post at the Sloane Letters Blog and this post by Alun Withey.

____________

1. Ambrose Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgeon … (London, 1634), 785.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid, 785-6.

4. Ibid, 786.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid, 787.

7. Nicholas Culpeper, Culpeper’s School of Physick (London, 1678),154-5.

8 Wellcome MS 2535/49.

9.Ambrose Paré, The Workes of the Famous Chirurgeon , 786.

© Copyright Jennifer Evans all rights reserved.

Here’s an interesting recipe for ‘horses, cows, dogs that are bitt by a mad dog.’ This calls for primrose roots and ‘star of the earth’ mixed with one ‘dry mouse ear’ and a second ‘green mouse ear’ boiled in milk along with ‘the black of one crabs claw’ [sic]. This was to be sweetened well with Venice or London treacle and then used as a drench three mornings in a row.

I found this in a manuscript dating from roughly 1675 – 1800 at the Wellcome Library in London and would be happy to share the reference if anyone is interested!

That is interesting, I wonder why they were particular about the two types of mouse ear? I didn’t really have space in this post to go into the treatment of animals for the same problem, may have to do another post in the future.

Some of my favourite MS recipes are ‘for the bite of a mad dog’… Along with Sally Osborn, who is working on recipes of this ilk in the 18th century, I am interested in these recipes as they seem to supersede recipes for the plague in 18th century MSS, as responses to one of the great ‘uncurables’… Mad dogs were the medical bogey’men’ of the period: fear of them far outstrips recorded incidences of human hydrophobia, as far as records show.

By the middle of the 18th century, several key ‘cures’ were circulating: the Calthorp Church recipe (so-called because it was to be found in Calthorp church); the Tonquin cure (so-called as it was supposedly brought back from Tonkin); and the Ormskirk cure (which was commercially produced in the Lancashire region, with Amanda Vickery’s ‘Gentleman’s Daughter’, Elizabeth Shackleton partly involved in the family business selling it). The circulation of these was aided by magazines like the Gentleman’s Magazine, and by ‘scare’ stories in newspapers.

I thoroughly recommend John Blaisdell’s articles on the the subject of ‘mad dogs’ and attitudes towards them in England, before the period covered by Mick Warboys’ book on rabies in 19th century England for more information!

Fantastic thank you, I will check out the readings – I would be very happy to post a blog on 18th century mad-dog cures if either you or Sally were interested? It was the frequency of them that struck me. They are not my main focus of research but they were hard to miss.