In recent years we have been repeatedly told that modern media culture, with its air-brushed images of perfect bodies, has created generations of young people overly concerned with their body image. More than this we are told that the attempts to attain such beautiful bodies, through fad-diets and plastic surgery etc., are causing a variety of health problems. We are also bombarded with the idea that unhealthy bodies, and in particular overweight bodies, are unattractive. Body types and deformities caused by a range of diseases are seen as a source of fascination, and sometimes entertainment, and are displayed as different in television documentaries. But the importance of a beautiful body and its relationship to health is not something unique to modern culture; early modern men and women also lived in a world where body image was important and where their body’s appearance was linked to both their attractiveness and their health. This can be seen in a variety of ways, one of the most basic is that printed medical texts, and hand written collections of medical remedies, often contained not only recipes for medicines but also cosmetics. Many included methods for removing unwanted hair or for clearing the complexion and removing freckles.

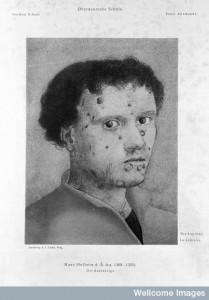

The connection between health and attractiveness could be very obvious, especially in relation to sexual health problems like venereal disease. The pustles, pox marks and facial deformities caused by syphilis not only made a person  physically unattractive but also morally unattractive; the marks upon their bodies showed the world that they had indulged in sinful behaviours. When medical writers wrote about the types of people that caught venereal diseases, they were not described as unfortunate or unlucky, instead they were tarred with a range of negative labels which implied that they, unlike the rest of society, were not able to control their sexual desires and so indulged to freely or for the wrong reasons (for many early modern men and women the only reason to have sex was to conceive a child). John Hester described the beginnings of venereal disease as ‘a fit sawce for that sweet sinne of Lecherie.’[i] This was a relatively mild, if condescending remark, compared to those like John Harris who listed the many symptoms of syphilis and declared that these were,

physically unattractive but also morally unattractive; the marks upon their bodies showed the world that they had indulged in sinful behaviours. When medical writers wrote about the types of people that caught venereal diseases, they were not described as unfortunate or unlucky, instead they were tarred with a range of negative labels which implied that they, unlike the rest of society, were not able to control their sexual desires and so indulged to freely or for the wrong reasons (for many early modern men and women the only reason to have sex was to conceive a child). John Hester described the beginnings of venereal disease as ‘a fit sawce for that sweet sinne of Lecherie.’[i] This was a relatively mild, if condescending remark, compared to those like John Harris who listed the many symptoms of syphilis and declared that these were,

‘the effects of that detestable sin, when it meets with that detestable disease, the Venereal Pox, which by God’s just judgment hath assailed Mankind, not only in France, but in most parts of the World, as a scourge or punishment, to restrain the too wanton and lascivious lusts of impure Persons, causing them to receive in themselves that recompence of their errour’.[ii]

As well as the symptoms of certain diseases, it is clear that some medical writers also viewed a range of bodily deformities as straddling the line between medical problem and aesthetics. In particular we can see this if we look at just one seventeenth-century medical text, A Golden Practice of Physick. This book was originally writt![V0004693 Felix Plater [Platter]. Line engraving, 1688.](https://earlymodernmedicine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/platter-168x300.jpg) en by Felix Platter a successful Swiss physician whose patients included German princes and the nobility. It was published in English in 1662 by Abdiah Cole and Nicholas Culpeper, both of whom were also medical practitioners. One the chapters included in the book is ‘Of Deformity’ , in which Platter, Cole and Culpeper list at length a range of bodily problems and how to cure them, including extra digits, a lack of teeth, crooked legs, and goggle eyes.[iii] In many cases the authors focused on the medical nature of these problems and offered remedies to cure them, but in several cases they were not above commenting on the unattractiveness of these bodies. The swelling of a limb through ‘the aboundance of flesh or fat’ was considered by them to look ‘unseemly’, as were women whose breasts had sagged: ‘the thinness of Womens breasts which is a Deformity, not when they are little, for that is accounted an ornament, but when they are lank and hang down in young Women especially is accounted unseemly.’ [iv]

en by Felix Platter a successful Swiss physician whose patients included German princes and the nobility. It was published in English in 1662 by Abdiah Cole and Nicholas Culpeper, both of whom were also medical practitioners. One the chapters included in the book is ‘Of Deformity’ , in which Platter, Cole and Culpeper list at length a range of bodily problems and how to cure them, including extra digits, a lack of teeth, crooked legs, and goggle eyes.[iii] In many cases the authors focused on the medical nature of these problems and offered remedies to cure them, but in several cases they were not above commenting on the unattractiveness of these bodies. The swelling of a limb through ‘the aboundance of flesh or fat’ was considered by them to look ‘unseemly’, as were women whose breasts had sagged: ‘the thinness of Womens breasts which is a Deformity, not when they are little, for that is accounted an ornament, but when they are lank and hang down in young Women especially is accounted unseemly.’ [iv]

Some of these problems were hazardous for men’s masculinity. For example, the authors note some men were born with three testicles, although they explain that the third testicle was often just an insensible growth.[v] They also included in their list of deformities obesity and a body image issue that we perhaps think of as very modern ‘man boobs’: ‘when the Papps are too large, and cover the whol[e] Breast and would go farther if not restrained, and hinder breathing by their weight: such are those fat Men who have great breasts’.[vi] They also described Alopecia, hair loss, as a deformity and explained that ‘The same happens to the Beard, the hair falls off inordinately and leave it thin or the Chin bare’.[vii] This in particular may have been troubling for men as the beard was a very important means of asserting manhood. [viii] The growth of a beard was related to the heat and potency of the male body and was a sign of full adult virility. Indeed the authors went on to explain that those whose beards grew too slowly were deformed: ‘as the chin where mans beard should grow hair come forth slowly and make them who are men seem still Children’. [ix] Finally they stated that men who never grew a beard and ‘remain beardless, it is uncomely and makes them wrinkled in the face as years increase, and as the Comaedian saith look like old Women.’ [x] In this case something we today think of as merely a style choice was an important marker of bodily health and male potency, men without beards were not men at all they were like children or old women.

[i] John Hester, The pearle of Practice, or Practisers pearle, for phisicke and chirurgie. Found out by I. H. (a spagericke or distiller) amongst the learned observations and proved practises of many expert men in both faculties. Since his death it is garnished and brought into some method by a welwiller of his (London, 1594), p.59.

[ii] John Harris, The divine physician, prescribing rules for the prevention, and cure of most diseases, as well of the body, as the soul demonstrating by natural reason, and also divine and humane testimony (London, 1676), p.34.

[iii] Felix Platter, Abdiah Cole, Nicholas Culpeper, A Golden Practice of Physick. In Five Books, and Three Tomes. … (London, 1662), pp. 500- 502.

[iv] Felix Platter, Abdiah Cole, Nicholas Culpeper, A Golden Practice of Physick, pp. 500- 502.

[ix] Will Fisher, ‘The Renaissance Beard: Masculinity in Early Modern England’ Renaissance Quarterly Vol 54/1 (2001) 155-87

[x] Felix Platter, Abdiah Cole, Nicholas Culpeper, A Golden Practice of Physick, p. 501

[vii] Felix Platter, Abdiah Cole, Nicholas Culpeper, A Golden Practice of Physick, p. 501.

© Copyright Jennifer Evans. All rights reserved.