In her first book Sara Read explores the understanding of female bleeding in early modern England. Menstruation and the Female Body in Early Modern England brings together discussions of the key moments of bleeding in a woman’s life; menarche, menstruation, hymenal bleeding and bleeding in childbirth. Read uses both medical literature and personal writings to uncover how women themselves may have thought about this bleeding and in some cases dealt with it. For those unfamiliar with the subject, the book opens with a tour through the varied language used to describe menstruation and bleeding. One popular term in use at this time was the ‘flowers’, which, it has been suggested, was used because many believed that after flowers fruit would follow. This term was, then, related to the fertility of the female body. Another suggestion about this term was that it was adopted from the process of brewing, flowering was the fermenting of beer; however, Read is more sceptical about this particular connection.

In her first book Sara Read explores the understanding of female bleeding in early modern England. Menstruation and the Female Body in Early Modern England brings together discussions of the key moments of bleeding in a woman’s life; menarche, menstruation, hymenal bleeding and bleeding in childbirth. Read uses both medical literature and personal writings to uncover how women themselves may have thought about this bleeding and in some cases dealt with it. For those unfamiliar with the subject, the book opens with a tour through the varied language used to describe menstruation and bleeding. One popular term in use at this time was the ‘flowers’, which, it has been suggested, was used because many believed that after flowers fruit would follow. This term was, then, related to the fertility of the female body. Another suggestion about this term was that it was adopted from the process of brewing, flowering was the fermenting of beer; however, Read is more sceptical about this particular connection.

Having explored the language of bleeding, the book moves through a series of chapters that follow the chronology of female ageing from menarche (the first menstrual period) to menopause. These moments, Read argues, marked shifts in female status. The first, menarche, marked the transition from girl to woman. The young woman’s bodily readiness for marriage was demonstrated by the appearance of menstrual blood which signified fecundity. The second chapter examines the beliefs that surrounded early and delayed onset of menstrual bleeding. A girl’s body demonstrating this particular sign of sexual maturity before the age of 12 was considered to be possible but highly unusual. Of even more concern, Read shows, was late development. This caused the body to lapse into disease and ill-health, particularly ‘Greensickness’, also known as white fever and later known as chlorosis. Helen King has previously written about this but Menstruation and the Female Body contributes a rich layer of personal testimony to this discussion, showing that women themselves believed they had succumbed to such a disease. Interestingly, Read argues, that the discourse of greensickness in the early modern period was dominated by relationships between fathers and daughters, who struggled to negotiate the move of the female body into adult married life.

Once this difficult transitional stage had been navigated, many women experienced a menstrual cycle for many years, although this was not always regular. Chapters four and five consider how this bleeding was understood and dealt with. Read shows that it was perhaps normal for women to bleed into their clothes with the use of cloths and pads being reserved for those who experienced heavy bleeding. Importantly it is shown that several husbands recorded details of their wives cycles and were rather open in their discussion of menstrual bleeding. Conversely women made only veiled references to their ‘monthlies’, often in relation to potential pregnancy. This chapter also considers that for some women bleeding itself was not the only inconvenience; some experienced pain and other unpleasant side effects. Samuel Pepy’s wife, Elizabeth, suffered from painful menstruation and Pepy’s recorded in his diary leaving his wife ‘sick on her menses at home’ while he went to church (p.100).

The next transitional bleed experienced by the female body was hymenal bleeding, which marked the final step into womanhood and signified the moment from which a woman could potentially become a mother. Including this form of bleeding is a significant contribution to the literature in which this bodily function is rather neglected. This chapter explores the medical debate about where this blood came from and highlights that it was considered to be the same substance as menstrual blood. Seeing blood lost in this way fed into the suggestion that intercourse could promote menstruation and so provide a cure for greensickness. Medical writers explained that sex stretched the reproductive organs causing the veins and arteries in the vagina and ‘neck of the womb’ to dilate and burst releasing the pent-up menstrual flow. The chapter also explores the language of conquest and violence used to describe the blood lost by virgins and the eroticisation of this blood in literature.

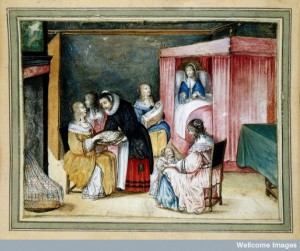

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Following this blood loss a woman was liable to fall pregnant and so the book moves on to look at lochial bleeding, the bleeding that follows childbirth. Medical treatises expressed a concern about how much blood should be lost at this time and there was some suggestion that it would be different depending on the sex of the child: male children were considered more perfect and hotter and so it was thought they would use up more of the blood provided in the womb for their nutrition. Read also shows that women themselves expressed concerns about excessive blood loss at this time and the weakened state it could leave them in. Finally the book turns to the loss of regular bleeding, menopause, and to the ways in which women were anxious about this moment because it signalled the end of their child-bearing years. This was potentially disruptive to a woman’s position in society, however, it would appear that most women who recorded their life events in one way or another were rather silent about this issue. When it was mentioned it was often in relation to ideas about aging to quickly or experiencing disease and disorders associated with the older body.

Menstruation and the Female Body weaves together medical and personal literature to uncover how women themselves may have thought about the moments in their lives when their bodies bled. The book demonstrates that in comparison to men women were rather secretive about these moments and used euphemism and veiled language to talk about these intimate bodily processes. Throughout Read highlights the difficulty this has left historians for accessing beliefs and practices connected to menstruation and menstrual blood. One area that is absent in this book is magic. On the continent menstrual blood was often associated with magical properties and love magic. This seems to be almost entirely absent in England and Read’s discussion highlights that these women never seemed to think about menstrual blood in this way. One difficulty with this discussion of menstruation, again perhaps caused by the nature of the sources, is the way in which medical theories are drawn upon. In places it is suggested that medical theories did not strongly influence everyday understanding of the body, in others, conversely, a strong connection is made between medical ideas and the beliefs of ordinary women. This may indeed have been the case, with religion or traditional beliefs being more influential for certain types of bleeding, however, this relationship is perhaps something scholars need to continue to probe and tease out. In bringing together the various moments when a woman’s body bled Menstruation and the Female Body adds much to the historiography and allows us to think beyond isolated incidents of menstrual bleeding to consider the importance of a woman’s body throughout her life.