The Therapies Series

In our therapies series we have looked at cupping, bloodletting, pessaries and trepanning. In this post we are going to take a look at another early modern therapeutic method – the use of fumes and smells.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Smells were very important in understandings of early modern health. Scent was connected to ideas of environment, which was one of the six non-naturals men and women regulated in order to maintain the balance of their humours and their health. Environments with clean fresh air were thought to be healthier than others. Fenland areas and areas of standing water and stagnant air, like the low-lying areas of Essex, were believed to pose a hazard to health because they were characterised by putrefaction. Moreover, the filth of towns and cities was thought to make these areas unhealthy.1 This knowledge was put to practical use by practitioners and patients. For example, Carole Rawcliffe has demonstrated how spaces – particularly gardens, orchards and parks – were a ‘major weapon in the relentless battle against disease’.2 In part this was related to ideas about the healthfulness of green and pleasant environments and in part to the health benefits of pleasant aromas produced by odoriferous plants.3

Smells, in addition to being present in an environment, could be manipulated and used as medical remedies. But smells were a complex entity and not one that was fully understood at this time. Richard Palmer has looked at this in detail and explains that most early modern medical writers subscribed to the theory that the two small porous membranes protruding from the brain into the naval cavity were the organs of smell.4 Despite this general agreement on the organ of smell, the way in which odours were perceived, and indeed what odours actually were, was much more uncertain. Many early modern medical writers, including Helkiah Crooke, believed that smells were invisible particles that penetrated the organs in the nasal cavity and touched the brain.5

Pungent aromas and fumes were used to ward off certain illness. They were thought to combat the corruption that miasmas (smells of putrefaction) could produce in the body. This was perhaps most famously used to ward of the plague. People burnt fires in their homes containing aromatic herbs, or carried posies with them. Holly Dugan has explained that rosemary was associated with rituals of betrothals, marriages and funerals, but during outbreaks of plague was used extensively giving it new connotations and meanings.6

Perhaps more surprisingly smells were also used to treat a range of uterine disorders, particularly the prolapses of the womb and ‘fits of the mother’. This was because many at the time believed that the womb was ‘similar’ to the brain – the primary organ of smell – and so was particularly prone to being affected by smells. Not everyone believed this though and some like Daniel Sennert tried to convince others that the womb was not an organ of scent:

it is probable to me that the womb is not delighted with Scents as Scents, for the Privities have no smelling, and the sense of smelling doth not reach so far; but the quality by which it is well or ill, is occult, and not to be explained, and not to be separated from the Odors.7

In the disease known as the suffocation of the mother, or the fits of the mother the womb was believed to rise towards the diaphragm inducing breathlessness. One cause of this and the means to treat the disorder was through the use of pungent smells. It was believed that the womb would be drawn towards sweet smells, so placing them at different points on the body would return the womb to its correct position. Nicholas Culpeper, for example, explained in the most basic terms that,

in the fits of the Mother, which is the Womb turned upwards, stinking things applied to the Nose, and sweet things to the Matrix, reduce it, but sweet things applyed to the Nose, and stinking things to the Matrixe produce it.8

The pungent pongy substances used in this disorder were quite diverse, including burnt partridge feathers, leather, asafoetida, galbanum, rue, civet, musk and cloves.

Similar remedies were used for uterine prolapses, again because it was believed that sweet-smelling substances placed under the nose would draw the womb up, while stinking and foul-smelling substances placed at the genitals would force the womb upwards, and back into its original position. The surgical treatise of Ambrose Paré recommended that ‘stinking fumigations must bee used unto the privie parts, and sweet things used to the mouth and nose’ if the womb had descended into ‘its own neck’ (the vagina but no further).9

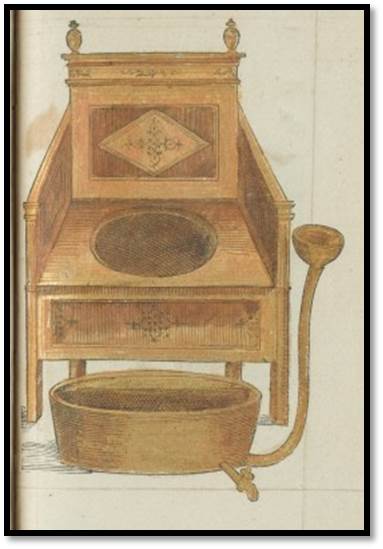

There were several methods recommended for directing fumes and smells into the womb. Firstly it was suggested that a woman could crouch over a small fire or other source, making sure that her skirts acted as an enclosure: ‘Put a Fume (Saith he) under the Coats of a woman, and let her be close clothed about‘.10 Secondly a ‘tunnel’ could be used: ‘let a fume be made underneath thorow a Tunnell’.11 Finally a special stool, with an appropriately placed hole, could be used: ‘put the pot under some stool, having a hole in the midst thereof: through which let the woman receive the fume up into her privy parts’.12

There were several methods recommended for directing fumes and smells into the womb. Firstly it was suggested that a woman could crouch over a small fire or other source, making sure that her skirts acted as an enclosure: ‘Put a Fume (Saith he) under the Coats of a woman, and let her be close clothed about‘.10 Secondly a ‘tunnel’ could be used: ‘let a fume be made underneath thorow a Tunnell’.11 Finally a special stool, with an appropriately placed hole, could be used: ‘put the pot under some stool, having a hole in the midst thereof: through which let the woman receive the fume up into her privy parts’.12

Smells were then powerful because they moved beyond the surface of the body in to its interior where they could affect and change the organs and bodily fluids to cause disease and importantly to improve health. They could be used in a range of conditions that are perhaps surprising to a modern reader.

To read more about the use of these smells for infertility you can read my article in Historical Research.

____________

1. Andrew Wear, Knowledge and Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680 (Cambridge, 2000), p. 189-91.

2. Carole Rawcliffe, ‘Delectable Sightes and Fragrant Smelles’: Gardens and Health in Late Medieval and Early Modern England, Garden History, 36/1 (2008), 3-21.

3. Ibid, p. 8.

4. R. Palmer, ‘In bad odor: smell and its significance in medicine from antiquity to the 17th century’, in Medicine and the Five Senses, ed. W. Bynum and R. Porter (Cambridge, 1993), pp. 61–8, 62.

5. Cited in Holly Dugan, Ephemeral History of Perfume, p. 12.

6. Ibid, p. 99.

7. D. Sennert, Practical Physick; The Fourth Book . . . By Daniel Sennertus, N. Culpeper, and Abdiah Cole . . . (London, 1664), p. 63.

8 Nicholas Culpeper, Select Aphorismes: Concerning the operation of Medicines according to place in the Body of fraile Man (London, 1655) p. 77.

9. Ambrise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion, (London, 1634), p. 935.

10. Sennert, Practical Physick, p. 136

11. Jakob Rueff, The Expert Midwife: Or, An Excellent and Most Necessary Treatise of the Generation and Birth of Man . . . (London, 1637), p. 53.

12. William Sermon, The Ladies Companion, Or, English Midwife Wherein is Demonstrated the Manner and Order of How Women Ought to Govern Themselves . . . (1671), p. 8.

© Copyright Jennifer Evans, all rights reserved

6 thoughts on “Fumigating for Health”

Comments are closed.