by Amie Bolissian McRae

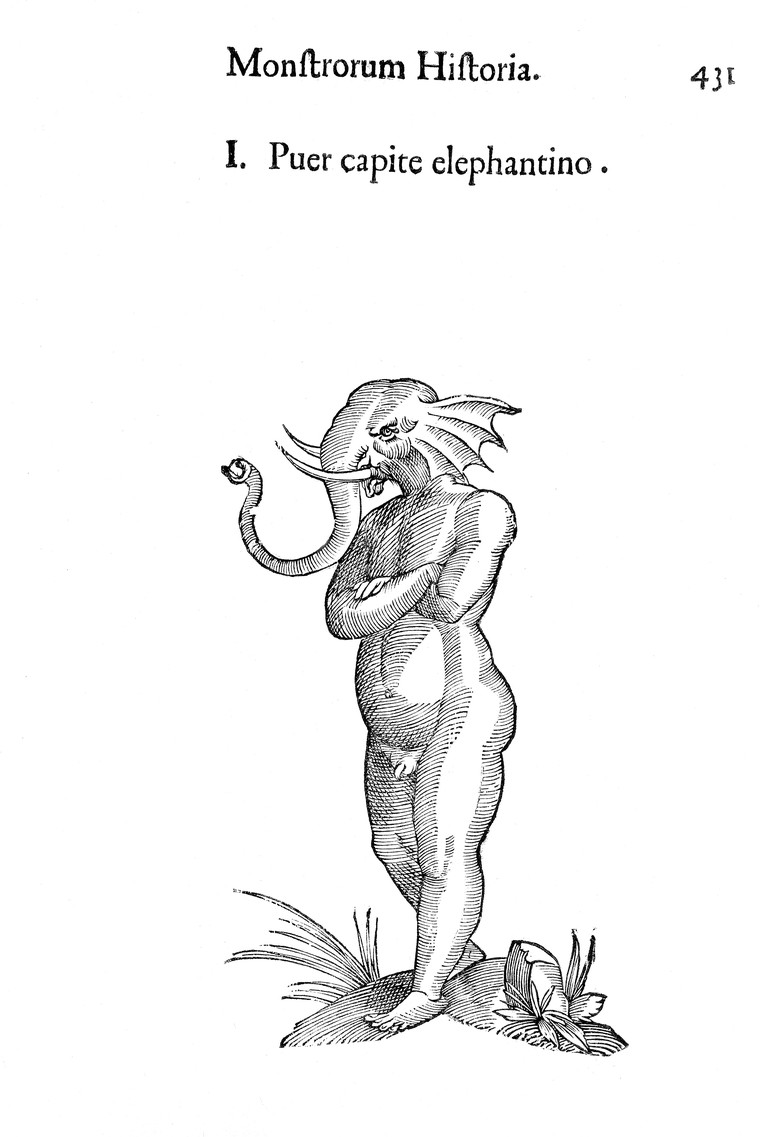

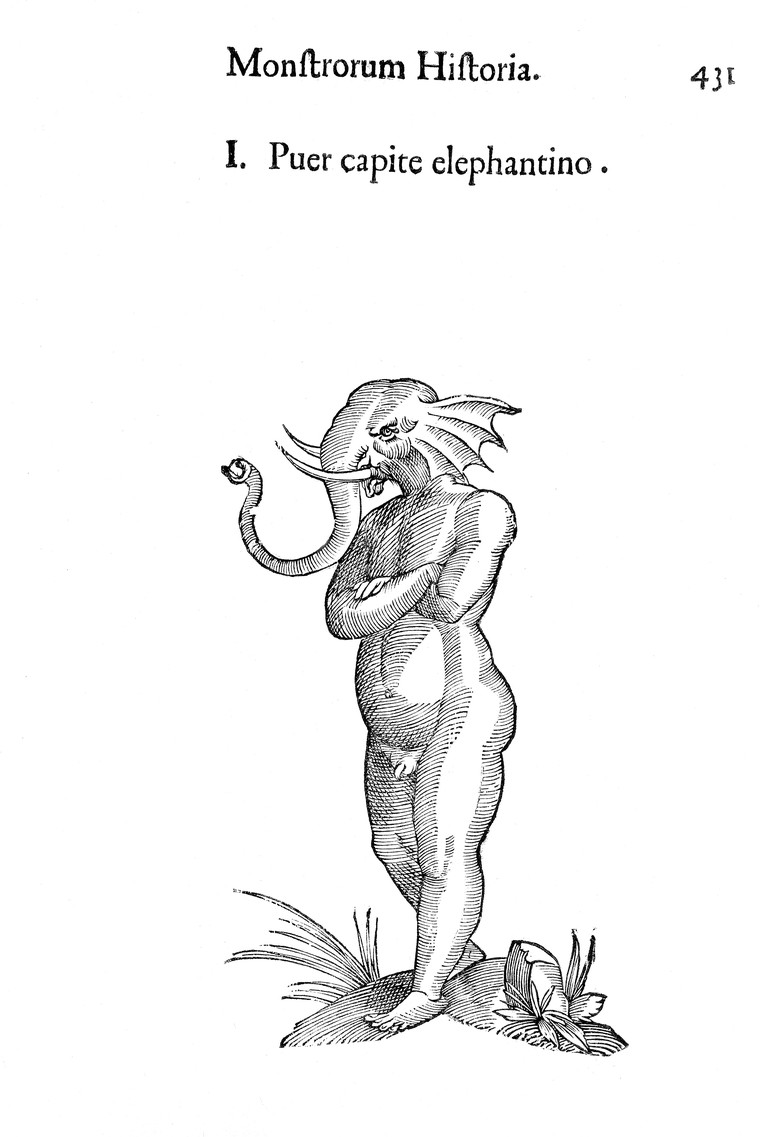

In sixteenth-century Leuven, a troubled man sent for a physician to help him with his unusually long nose. The man believed that his nose was of ‘such a prodigious length’, it resembled the ‘snoute’ of an elephant. It hindered him in everything he did, to the extent that sometimes it ‘lay in the dish’ where his supper was served. His physician, at this point, artfully and carefully, ‘conveighed a long pudding’ onto the nose of the desperate man, and then with a Barber’s razor ‘finely cut away’ the offending pudding nose while his patient was drowsy from a sleeping draft. The physician prescribed him a wholesome diet and sent the man away, relieved of his extraordinarily long nose, and the burden of ‘fear of harme and inconvenience’.[i]

This case history was described in the English translation of the medical treatise, The Touchstone of Complexions (1576) by the Dutch physician, Levinus Lemnius, as an example of ‘melancholicke’ fantasy. Instead of assuming the man was possessed by a malevolent spirit or demon (a possible diagnosis at this time),[ii] that he was a ‘lunatic’ and beyond treatment, or dismissing his delusion to his face, the sixteenth-century physician in the story entered into the world of the ‘phantasie’ to try and help his patient’s obvious distress.

We very rarely read histories of incidents from this period where physicians are concerned for the emotional and mental wellbeing of their patients to this degree. Usually the tendency has been to emphasize the ‘barbarous and debilitating’ treatments of early modern medicine – its bloodletting, purging, and surgery without anaesthetic, or to highlight the moralizing religious doctrine behind treatments of illnesses of the mind or ‘passions’.[iii] Yet, here was a doctor trying an imaginative solution to a problem he believed stemmed from an imbalance of the humour ‘melancholy’ in his patient’s body.

Further examples follow. One tells of a man whose ‘hartstryngs’ were ‘swolne with melancholie humour’ causing him to believe that he had live frogs and toads in his stomach, which ‘gnawed & eate asunder his Entrailes’. His physician, recognising that ‘Melancholike folkes will hardly be disswaded or brought from their opinions’, gave his patient a laxative and an enema, and arranged for some ‘crawling vermin’ to be put into the basin of the man’s ‘close stool’, or toilet cabinet. When the purgatives worked and the patient took a look at the squirming results, he ‘rested satisfied in minde’.

A third example described a man who firmly believed that his ‘Buttocks were made of glasse’, which prevented him from ever sitting for fear of shattering himself, and a fourth case described ‘a certaine Gentleman’ in a ‘fooles paradise’ who was so utterly convinced that he was dead that he refused to eat or drink. His ‘frends and ‘acquaintaunce’, after a week were worried that he might starve to death, so they arranged for some people dressed as shrouded corpses to eat in front of him, and persuade him to join them in their posthumous feast. The gentleman happily ate his fill and they managed to slip him a sleeping draft, the sleep being credited with his subsequent cure.[iv]

There could be a certain ‘absurd’ humour to these stories, which Lemnius himself admitted, but neither the patients’ healers, nor their friends, took the sufferers fears or danger lightly.[v] Lemnius presented these stories as real cases, that he witnessed or heard about, but even if they were invented or embellished to make his point, the serious proposition behind these case histories remains: a strong ‘phantasie’, diagnosed as brought on by physiological causes, should be treated cautiously, with understanding, imagination, and attention to the needs of the person. Diet and sleep was emphasised, a cleansing of corrupted humours, and a balancing of the temperature and moisture in the brain. And nobody was incarcerated for being a ‘doting fool’, or exorcised of any demons.

Amie Bolissian McRae is a Wellcome-funded doctoral researcher at the University of Reading, specialising in medicine and emotions in early modern England. Her PhD study, The Aged Patient in Early Modern England, investigates medical understandings and treatments of disease in old age, and explores the personal experiences and feelings of older patients, and those that cared for them, in England, c.1570-1730.

____________________________________

[i] Levinus Lemnius, The Touchstone of Complexions, (Series The Touchstone of Complexions, 1576), f.150v.

[ii] See: Andre Du Laurens, A Discourse of the Preservation of the Sight: Of Melancholike Diseases; of Rheumes, and of Old Age., (Series A Discourse of the Preservation of the Sight: Of Melancholike Diseases; of Rheumes, and of Old Age., 1599), p.100.

[iii] M. Macdonald, Mystical Bedlam: Madness, Anxiety and Healing in Seventeenth-Century England (Cambridge University Press, 1983), p.46.

[iv] Lemnius, Touchstone, f.151r.- f.152.r.

[v] Lemnius, Touchstone, f.150.v; f.151.v.

Ganesha!

Very interesting!