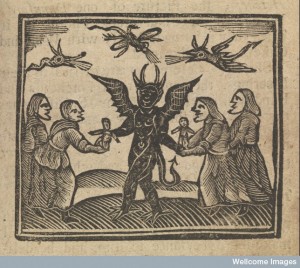

In The Witches of Huntingdon (1646) the author John Davenport salaciously outlined Elizabeth Weed’s involvement with three demons: he wrote that ‘the office of the man-like Spirit was to lye with her carnally’.1 This was not an isolated incident: the idea of witches copulating with the devil, or demons, was widely discussed in early modern Europe, and caused consternation and anxiety for writers at the time. This blog post will consider this phenomenon and show that medical understanding of sex and reproduction were central to these discussions. In particular demonology writers were concerned about whether sex with the devil could ever result in pregnancy and progeny.

Walter Stevens has investigated the many stories of demonic copulation from the early modern period in book Demon Lovers: Witchcraft, Sex and The Crisis of Belief.2 He stresses that from 1400 onwards there was a repetitive insistence by demonology writers that witchcraft consisted of maleficia and corporeal interaction with incarnate devils.3 This, he argues, was evidence of theologian’s anxieties about the ability of demons to be corporal beings on earth, which overcame the idea that demons and angels were purely spirit based beings.4 Sex thus provided valuable proof that the spirit world existed.

Walter Stevens has investigated the many stories of demonic copulation from the early modern period in book Demon Lovers: Witchcraft, Sex and The Crisis of Belief.2 He stresses that from 1400 onwards there was a repetitive insistence by demonology writers that witchcraft consisted of maleficia and corporeal interaction with incarnate devils.3 This, he argues, was evidence of theologian’s anxieties about the ability of demons to be corporal beings on earth, which overcame the idea that demons and angels were purely spirit based beings.4 Sex thus provided valuable proof that the spirit world existed.

Fertility and childbirth were also important contexts for understanding witchcraft accusations in the seventeenth century. Lyndal Roper’s work on European witchcraft has shown that many of these stories focused on motherhood, early infancy and the birthing chamber.5 Often the ‘witch’ was accused of causing death during childbirth or the death of a new-born infant. Magdalena Bollmann, for instance, attended the birth of several women in her village. Some of these women suffered terrible pain and illness, and others unfortunately lost their babies Bollmann was subsequently blamed for these misfortunes. Roper points out that in this case, as in many others, Bollmann was older than the women who testified against her and at the end of her childbearing years.6 In some cases, but not all, it was women who interfered with the natural maternal role and process that were likely to be classed as a witch.

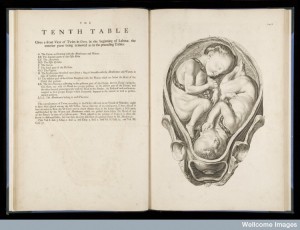

In early modern treatises having sex with the devil was unambiguously framed within the humoural understanding of the reproductive body and conception. Many theorists and writers discussed whether sex of this kind was reproductive. In particular they questioned whether and how the devil could convey seed into the womb, and whether the devil’s body was ‘hot’ enough to be potent. We can see these concerns in the printed trial records produced throughout the seventeenth century. In The Life and Conversation of Temperance Floyd; Mary Lloyd and Susanna Edwards (1687) it was stated that Temperance made a free confession ‘that the Devil assumeing [a] cold Body had frequent carnal knowledge of her’.7 Similarly in The Kingdom of Darkness (1688) it was noted in one case that the devil appeared to Rebecca West as she was going to bed ‘and said he would marry her, which she could not refuse, whereupon he kissed her but was as cold as clay’.8 Although these authors didn’t explain why the temperature of the devil’s body was important, the populace of early modern England would have understood that a cold body was not able to reproduce. The very presence of these statements therefore highlights how important it was for writers and readers of these texts to establish that the devil couldn’t have children. In demonological texts from the period much more detail was provided on this issue. Authors of these treatises described how the seed (or semen) of the devil lacked vital heat and so was too cold to be potent. The Daemonologie (1597) written by James I stated that whether the devil appeared in a spiritous form or had possessed the body of a dead person ‘whatsoever way he useth it, that sperme seemes intolerably cold to the person abused.’9

Other writers didn’t focus on the temperature of the seed, but argued more explicitly about whether sex with the devil was fertile. Reginald Scot’s Discovery of Witchcraft (1584) included the belief that ‘They [witches] use venery with a devil call’d Incubus, even when they ly in bed with their husbands, & have children by them, which become the best witches’.10 This idea that the devil could produce offspring was very alarming, it suggested that the devil could increase the number of his followers on earth; which put God fearing and innocent people at further risk from the malice of witches. Scot however explained that this was a very ridiculous assumption. James I’s Daemonologie also stressed that it was not possible for the devil to produce offspring: arguing that the devil could only create an illusion of pregnancy in a woman, ‘‘which he may doe, either by steering up her own humor, or by herbes, as we see beggars daily doe’.11

Other writers didn’t focus on the temperature of the seed, but argued more explicitly about whether sex with the devil was fertile. Reginald Scot’s Discovery of Witchcraft (1584) included the belief that ‘They [witches] use venery with a devil call’d Incubus, even when they ly in bed with their husbands, & have children by them, which become the best witches’.10 This idea that the devil could produce offspring was very alarming, it suggested that the devil could increase the number of his followers on earth; which put God fearing and innocent people at further risk from the malice of witches. Scot however explained that this was a very ridiculous assumption. James I’s Daemonologie also stressed that it was not possible for the devil to produce offspring: arguing that the devil could only create an illusion of pregnancy in a woman, ‘‘which he may doe, either by steering up her own humor, or by herbes, as we see beggars daily doe’.11

Some writers also discussed the fertility of the witches themselves.Reginald Scot also wrote about how the devil was motivated to try to conceive children and so wouldn’t waste seed when having sex with an old barren witch:

‘Either she is old and barren, or young and pregnant. If she be barren, then doth Incubus use her without decision of seed; because such seed should serve for no purpose. And the devill avoideth superfluity as much as he may; and yet for her pleasure and condemnation together, he goeth to worke with her…if she be not past children, then he stealeth [t]he seed away (as hath been said) from some wicked man being about that lecherous business, and therewith getteth young witches upon the old.’12

‘Either she is old and barren, or young and pregnant. If she be barren, then doth Incubus use her without decision of seed; because such seed should serve for no purpose. And the devill avoideth superfluity as much as he may; and yet for her pleasure and condemnation together, he goeth to worke with her…if she be not past children, then he stealeth [t]he seed away (as hath been said) from some wicked man being about that lecherous business, and therewith getteth young witches upon the old.’12

By asserting that sex with the devil was never procreative, writers were able to ease social anxieties about the potential for the devil to breed an army of Godless witches. However, this then raised another potential problem. If witches weren’t having sex in order to have children, then they must be being driven by rampant sexual desire and the pursuit of sexual pleasure. The moral and religious ideology of the early modern period argued that sex should was always to be undertaken with the aim of conceiving children. In The Witches of Huntingdon (1646) it was unambiguously stated that ‘the office of the man-like spirit was to lye with her [Elizabeth Weed] carnally, when and as often as she desired’.13 It was the witch who was responsible for these sinful acts, not the devil. Reginald Scot similarly asserted that it was ‘for her pleasure’ that the devil copulated with a witch.14 The idea that diabolical sex was liberated from the burden of conception and childbirth thus allowed for a group of women to be thought of as motivated solely by sexual pleasure and the pursuit of their own sexual gratification. This was deeply troubling as it played upon gendered ideas of the appropriate position of women in the sexual, and marital relationship, and on the notion that women were both inherently lusty and less capable of controlling their own desires.

___________________________________

1. John Davenport, The Witches of Huntingdon, Their Examination and Confessions; Exactly Taken by his Majesties Justices of the Peace for that County…The Reader May Make Use Hereof Against Hypocrisie, Anger, Malice, Swearing, Idolatry, Lust, Covetousnesse, and other Grievous Sins … (London, 1646). p. 2.

2. Walter Stevens, ‘Demon Lovers: Witchcraft, Sex and the Crisis of Belief.’, in Mary E. Weisner, (ed.) Problems in European Civilisation; Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe (Boston, New York, 2007), pp. 41-50. Stevens also explores these issues in his book Demon Lovers: Witchcraft, Sex and the Crisis of Belief (Chicago, London, 2002).

3. Ibid, p.41.

4.Ibid, p. 44-45.

5. Lyndal Roper, ‘Witchcraft, Nostalgia, and the Rural Idyll in Eighteenth Century Germany.’ Ruth Harris and Lyndal Roper (eds), The Act of Survival, Past and Present, Supplement 1, Vol. 1, January 2006, pp. 139-158.

6. Ibid, 141, 146-147.

7. Anonymous, The Life and Conversation of Temperance Floyd, Mary Lloyd; and Susanna Edwards Three Eminent Witches (London, 1687), p. 4.

8. R.B., The Kingdom of Darkness: Or, the History of Daemons, Spectres, Witches, Apparitions, Possessions, Disturbances, and other Wonderful and Supernatural Delusions, Mischievious Feats, and Malicious Impostures of the Devil (London, 1688), pp. 155-156.

9. James I, King of England, Daemonologie in forme of a Dialogue, Divided into Three Books (Edinburgh, 1597), p. 67.

10. Reginald Scot, Scot’s Discovery of Witchcraft: PROVING The Common Opinions of Witchces Contracting with Divels, Spirits, or Familiars; and Their Power to Kill, Torment, and Consume the Bodies of Men Women, and Children, or Other Creatures by Disease or Otherwise ….To Be But Imaginary Erroneous Conceptions and Novelties … (London, 1651), p. 26.

11. James I, Daemonologie, p. 68.

12. Reginald Scot, Scot’s Discovery of Witchcraft, p. 59.

13. John Davenport, The Witches of Huntingdon, p. 1-2.

14. Reginald Scot, Scot’s Discovery of Witchcraft, p. 59.

© Copyright Jennifer Evans all rights reserved.

This is so fascinating – thank you Jen. LOVE the woodcuts!

Just wondering if the association of witches with melancholy fitted in with this – for example, were there some of the women’s bodies in these witchcraft cases situated as cold and dry – and therefore barren? – not just older women, as cooling and drying was part of the aging process anyway, but younger women too.

I’m not sure about melancholy, but the most commonly discussed cause of barrenness was cold (and excessive moisture/ excessive dryness) so I’m not sure it would be possible to separate these from barrenness and age.