‘Sad and Incommodious things’: Miscarriage in Early Modern England.

‘Sad and Incommodious things’: Miscarriage in Early Modern England.

Before I started my current research project, I briefly explored how men and women in the early modern period responded to miscarriage. Perhaps unsurprisingly miscarriage could be a upsetting and scary prospect. One medical writer stated ‘Many Sad and incommodious things are wont to happen to women with child’.1 Angus McLaren in Reproductive Rituals has argued that the potential to miscarry was great at this time.2 So what if anything did early modern men and women think would prevent miscarriage, and importantly when was this intervention thought necessary (given that by the time a miscarriage was identified it would be difficult to prevent it)?

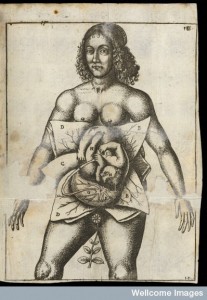

Miscarriage was thought to be the result of a range of hazards and dangers that faced the early modern pregnant woman. These could start at the moment of conception: Nicholas Culpeper explained that children conceived from weak seed, those that weren’t properly nourished in the womb and women who had overly straight wombs were all liable to suffer miscarriage, as were mothers who contracted fevers and inflammations or who suffered fainting, sneezing and coughing.3 A range of external factors were also thought to be dangerous including: cold air, malignant aspects of the stars, hemorrhoids, violent motions, carrying heavy burdens, blows to the belly or back and excessive passions such as anger, fear and sorrow.4 Midwifery manuals also warned people to be vigilant to the signs that warned of impending miscarriage: the breasts sagging, milk flowing from them, pain in the belly and back and shaking and trembling.

Although, these signs were included many midwifery treatises simply described their remedies for miscarriage for those who were liable to miscarry. This would suggest, perhaps, that only women who had been pregnant before would know to take these remedies – how can you know if you are likely to miscarry if it is your first pregnancy? Clare Hanson has suggested in A Cultural History of Pregnancy that the role of medical advisers during pregnancy was ‘providing reassurance’.5 Can we read the many remedies for preventing miscarriage, therefore, as a way of acknowledging the uncertainty women may have felt about the possibility of miscarriage and as a means to allay those fears. These remedies represent a means of active intervention and agency to try to prevent miscarriage and so may have given women a reassuring sense of control that the onset of an early stage abortion (abortion for early modern medical practitioners did not mean deliberately induced termination) did not inevitably lead to the loss of the foetus. Moreover by calming women’s fears these recipes may have removed some of the potential causes of miscarriage, fear and sorrow.

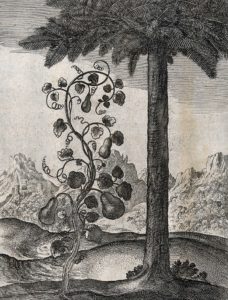

So what remedies were recommended to prevent miscarriage? There are many  different remedies suggested but a common theme in both the printed midwifery treatises and manuscript remedy collections kept was to lay a hot rag, poultice or piece of toast soaked in spices and wine to the belly. Jane Sharp’s midwifery treatise advised that to strengthen the child in the womb ‘Take two pound of the crumbs of the inward part of white Bread, Cammomile flowers one handful, Mastick two drams, Cloves half a dram, bruise them and mingle them well with some Maligo Wine and two ounces of rose Vinegar, boil them to a Pultiss and lay it on a double Cloth to the Os pubis‘ [the pubic bone].6 The recipe book of Elizabeth Okeover offered similar advice saying that a the woman should consume a particular remedy while ‘laying to her navell a Toste wett in Muskadine [wine].’7 The same recipe was also repeated in another un-named seventeenth century recipe book.8

different remedies suggested but a common theme in both the printed midwifery treatises and manuscript remedy collections kept was to lay a hot rag, poultice or piece of toast soaked in spices and wine to the belly. Jane Sharp’s midwifery treatise advised that to strengthen the child in the womb ‘Take two pound of the crumbs of the inward part of white Bread, Cammomile flowers one handful, Mastick two drams, Cloves half a dram, bruise them and mingle them well with some Maligo Wine and two ounces of rose Vinegar, boil them to a Pultiss and lay it on a double Cloth to the Os pubis‘ [the pubic bone].6 The recipe book of Elizabeth Okeover offered similar advice saying that a the woman should consume a particular remedy while ‘laying to her navell a Toste wett in Muskadine [wine].’7 The same recipe was also repeated in another un-named seventeenth century recipe book.8

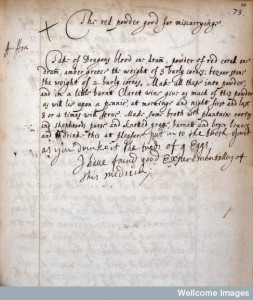

As seen in Sharp’s treatise and the recipe book image above, miscarriage remedies were often more complex than simply laying toast to the womb. They required time to produce and so it is worth thinking about when recipes were used; the recipe book of Madame Alice Cole may help us to do this. The recipes described above would perhaps have been applied when a pain was felt or the woman felt unwell, but Alice Cole’s book shows us that women did not simply wait for a danger to come upon them. Instead women would preempt potentially hazardous situations such as taking a long journey by horse or coach and would take particular remedies to counteract the danger they posed:

To prevent miscarrying or if one that is apt to miscarrie goe a journey let her take this powder morning and evening whilst shee journeys

Take of Dragons Blood the weight of 2 [ounces?] red corrall powdered one dram Ambergreece the weight of 2 barly corns, Besar [bezoar] ye weight of 3 barly corns, mix all these together and keep them close stoped in little vial glasse when you use take as much of it as lie upon a penny in a little clary water at nighte when you goe to bed, and in ye morning fasting and sleep after it to use it till you are out of [? &] safe of miscarrig[e].9

From these recipes then we can start to build a picture of women as attuned to both their bodies and the situations they were in during pregnancy. They would use remedies to help ensure that their child was carried to term if they feared that they were likely to miscarry, or had miscarried before, if they felt particular bodily symptoms and if they knowingly faced hazardous situations.

________________________

1. Anonymous, A RICH CLOSET OF PHYSICAL SECRETS, Collected by the Elaborate paines of four severall Students in Physick, And digested together; ViZ. The Child-bearers Cabinet (London, 1659?), p. 1.

2. Angus McLaren, Reproductive Rituals: The Perception of Fertility in England from the Sixteenth century to the Nineteenth Century (Methuen; London and New York, 1984), p. 47.

3. Nicholas Culpeper, Culpeper’s Directory for Midwives … (London, 1662), pp. 172-3.

4. Thomas Raynalde, The Byrth of Mankynde … (London, 1604), p.132.

5. Clare Hanson, A Cultural History of Pregnancy: Pregnancy, Medicine and Culture, 1750- 2000 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2004).

6. Elaine Hobby (ed.), The Midwives Book … (OUP; Oxford and New York, 1999), p.173.

7. Wellcome Library London, MS. 3712/52.

8. Wellcome Library London, MS. 7391/11.

9. Somerset Heritage Centre Taunton, DD/SF/9/4/6/.

© Copyright Jennifer Evans, all rights reserved.

The relative lack of attention to discussions of fertility, miscarriage, and perinatal mortality, compared with the attention given to contraception and abortion, is a classic case of our being misled by current interests.

Historians of medicine, and especially women historians, are likely to have between zero and two or three children. Having more would seem a misfortune to be avoided. Expressions of fear before childbirth are read as focused on maternal mortality. Why books by or for midwives should have begun with a discussion of male generative parts has been treated as mysterious or useless.

As in poor countries today, having many children might be regarded as insurance against early deaths. A late 17th-century preacher on the duty of maternal breastfeeding exempted the royal family, because of the need to produce Protestant heirs. It would be presumptuous to suggest that the failure of both Mary and Anne to be survived by the fruit of their wombs was a result of this exemption, but Queen Anne did her utmost to produce heirs. Similar considerations can be seen, throughout the social strata, concerning the need for children as heirs, as help, or as future caregivers. Repeated miscarriages or infant deaths were a source of intense concern.

Other considerations included the genuine love of children, an excess of which was a matter of concern for preachers. [see the death of Matthew Henry’s first son] There was the stain on a man’s virility that came from a lack of procreative success. There was also the inability of a man to perform his marital duty, used by women as grounds for separation or annulment.

The physiology of male generative parts was therefore a matter of inevitable concern for midwives. For most of their clients, fertility was more important than family limitation, at least until death rates declined. Only fornication and adultery made a decisive difference to priorities, for both men and women.

A careful reading of the expressions of fear might suggest that unbearable pain and perinatal mortality were the primary concerns of mothers-to-be. We have a few famous examples of women writing to their children or unborn children [see Elizabeth Jocelin] but diaries and letters do not bear out the overwhelming status of this particular fear. It is our concern about maternal mortality, rather than infant mortality, that shapes our attention. [The US rate of maternal mortality today, 50th in the world, is comparable to that of some of the better undeveloped countries, but the same is true of perinatal mortality.]

I think it is probably true that this field is shaped by modern concerns, whether this is conscious or not I wouldn’t like to say. I think the discussion of these issues is broadening out though. My doctoral research (Which will be out as a book soon) looked at the use of aphrodisiacs as an infertility medicine and considered both the male and female bodies. As part of this I wrote an article encouraging early modernists to re-assess the tendency to jump to the conclusion of ‘it was for abortion’ when considered the many drugs around for provoking menstruation. Fertility and infertility were immensely important at this time and I think there is still so much more we need to look at to consider this further. I am currently also part of a group of scholars writing a series of articles about infertility in the pre-modern world. My particular contribution is about male infertility -something which I feel is still woefully under-studied despite Berry and Foysters excellent work and call for a more inclusive history of fertility.

I did start a project on miscarriage – where the material for these blog posts has come from – however, it is a very difficult topic to access in the sources. But I would like to continue (and I am still gathering materials) looking at this in the future. It is interesting in the letter I used in the ‘Pain and Pearles’ post – I think- that he makes no mention of Mary’s fear/ emotional state/ greife but instead focuses on this as a medical episode to be recovered from.

There is a whole breadth of issues and topics related to childbirth/pregnancy/reproduction that still need more attention, but at least fertility/infertility are receiving much more scholarly attention at the moment.

Hi Jennifer,

I am commencing a 26 000 word thesis and my main area of interest is looking at the emotional aspects and responses to miscarriage in early modern England. I understand sources for this can be difficult to locate but I would appreciate any advice or recommendations!

Rachel

razrea2011@yahoo.com.au

Dear Rachel,

I would be happy to talk further about this by email. j.evans5 (at) herts.ac.uk Drop me a line