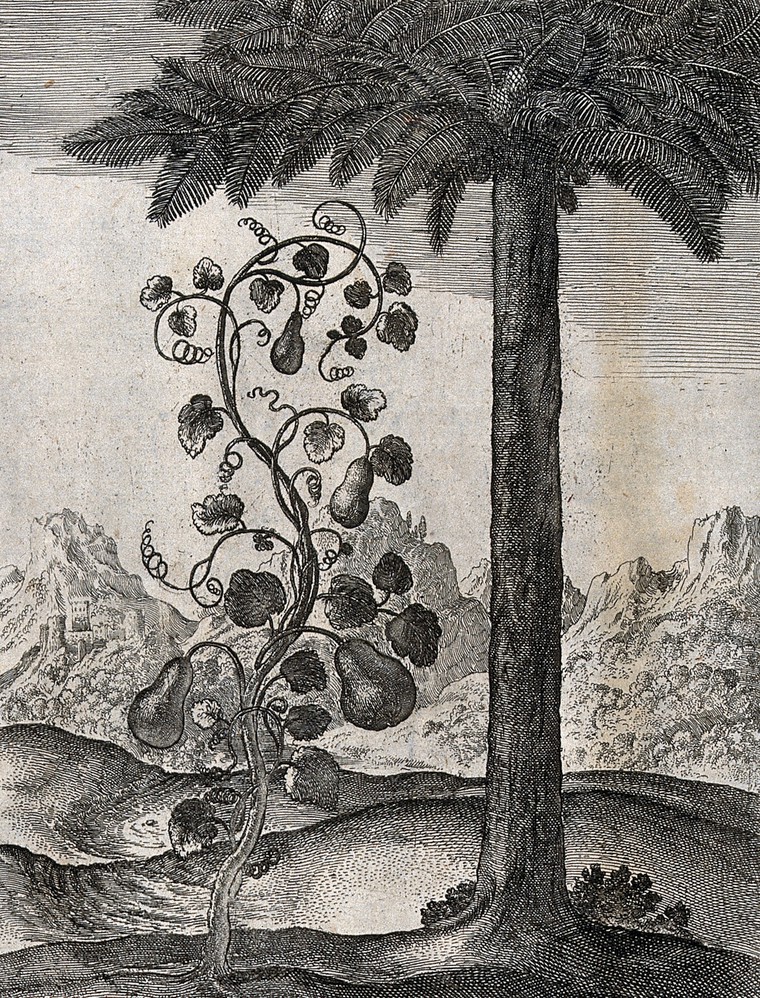

Being stuck inside the house on lock-down is certainly very challenging, but it has meant that I have had ample time to enjoy my rather petite pear tree explode into blossom.

Eating Fruit

Eating fruit in the early modern period was complicated in terms of health. David Gentilcore’s excellent book Food and Health in Early Modern Europe describes how fruit (and vegetables) were thought to be too cold and watery to be eaten regularly. Because of this, they offered little nourishment and produced thin, watery blood in the body. Even though fruit and vegetables were problematic, physicians didn’t condemn fruit eating. It could be useful for those whose bodies were too hot, and if they were cooked and spiced then they could be eaten more safely.1 In spite of these concerns fruit was eaten often across Europe and one medical saying went,

‘Raw pears a poison, baked a medicine be’.2

A controversial fruit

Despite this well-known saying medical authors were not all convinced that pears were medicinal. An early eighteenth-century copy of The Pharmacopoeia Londinesis, the catalogue of medicines for the Royal College of Physicians, explained that their were no medicinal virtues in the leaves of a wild pear tree.3 Likewise, A New English Dispensatory by James Alleyne stated bluntly that ‘Pears are never used in Medicine, that I know of’.4

Conversely, a translations of Rembert Dodoen’s A new herbal, or historie of plants explained that Pears eaten before meat were more nourishing than apples. They, he said, helped cure hot tumours and green wounds if laid on them when they first appeared. The leaves of the tree were also good for healing wounds.5 Similarly, an eighteenth-century reprint of John Pechey’s Compleat Herbal of Physical Plants agreed that pears were beneficial. Pechey said that ‘Pears are agreeable to the Stomach, and quench Thirst’. He emphasised though, like the saying claimed, that they were ‘best baked’. Dried Pears, it continued, helped stop fluxes of the belly (what we might call bouts of diarrhoea).6

Pears appear, then, to have had a rather contentious reputation. Unlike some foods and medicinal substances there was very little consensus about their virtues and uses.

______________________

- David Gentilcore, Food and Health in Early Modern Europe: Diet, Medicine and Society, 1450-1800, p.20.

- Ibid, p. 117.

- Pharmacopeia Londinensis: or, the London dispensatory furthhr [sic] adorned by the studies and collections of the fellows now living, of the said … (London, 1718), p. 50.

- James Alleyne, A new English dispensatory, in four parts. Containing, I. A more accurate account of the simple medicines, … IV. A rational account of the … (London, 1733), p.112.

- Rembert Dodoens, A nevv herbal, or historie of plants (London, 1619), p. 513.

- John Pechey, The compleat herbal of physical plants. Containing all such English and foreign herbs, shrubs and trees, as are used in physick and surgery. … (London, 1707), p. 182.

One thought on “Pear Power”

Comments are closed.