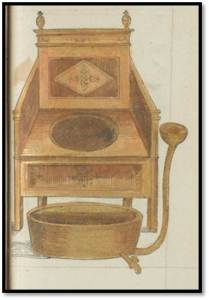

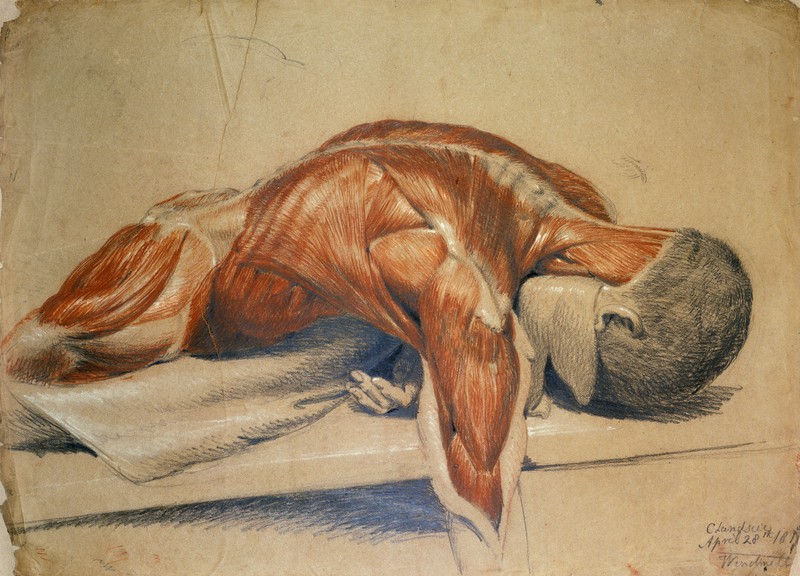

For centuries the need for the surgeon to learn more of the anatomy of the human body and to practice his art has required students of medicine to examine and dissect the bodies of the dead – obtained legally or otherwise – in private schools or, from the mid-eighteenth century, public hospitals. The work of Andreas Vesalius in Padua in the sixteenth century left a legacy of wonderful educational texts, beautifully illustrated.

For some, however, the horrors of the dissecting room disgusted and intrigued in equal measure, and the experience even now tests young stomachs.

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, when methods of preserving cadavers were basic and bodies often decomposing before they reached the dissecting room, it took great mental fortitude (and much dark humour) to sustain a man until the initial horror wore off and the identification of a body part with a living person ceased to terrify him. For many, however, that loss of a natural response to death was one that awakened in them the sense that they were about to lose something precious, which they resisted, and which persuaded them medicine was not for them.

Death Disease & Dissection: The life of a surgeon-apothecary 1750-1850 (published by Pen & Sword and available in a bundle with Maladies & Medicine) was inspired by knowledge that a number of doctors in training during this period were very creative young men and indeed this was seen as the age of ‘Romantic’ medicine in the same way that it is synonymous with the ‘Romantic’ arts. How did they cope and what did the men (and it was only men who were allowed to pursue this career path in this period) take from their training as inspiration for use in other fields?

Hector Berlioz, the nineteenth century French composer, originally intended to be a doctor and was sent to study medicine in Paris in 1821. However, it was his first experience of the dissecting room that made his decision to pursue music as a career instead easy. He offers a graphic description of that moment…

When I entered that fearful human charnel house, littered with fragments of limbs, and saw the ghastly faces and cloven heads, the bloody cesspools in which we stood, with its reeking atmosphere, the swarms of sparrows fighting for scrapings and rats in the corners gnawing bleeding vertebrae, such a feeling of horror possessed me that I leapt out of the window, and fled home as though Death and all his hideous crew were at my heels.

He went on to write his masterpiece, Symphonie Fantastique, brim full of opium induced dreams and nightmares of death and execution.

A description of the dissecting rooms of St Thomas’s Hospital in London indicates that matters were no better in Britain (and possibly worse, as bodies were often fresher in France). Bits of body, previously dissected, would float in liquid, or if bone, be pinned down as if to prevent escape. There was a large sink for students to wash their hands, and the body parts they were currently working on, many of which would be maggot-ridden.

The uncle of the famous doctor William Osler describes the rest of the scene:

On entering the room, the stink was most abominable. About 20 chaps were at work, carving limbs and bodies, in all stages of putrefaction, and of all colours; black, green, yellow or blue, while the pupils carved them apparently, with as much pleasure, as they would carve their dinners. One was pouring Terebinth on his subject, and amused himself with striking with his scalpel at the maggots, as they issued from their retreats.

The maggot stabbing was dangerous – a slip of the scalpel and a cut to the finger could introduce a lethal infection from which students could, and did, die.

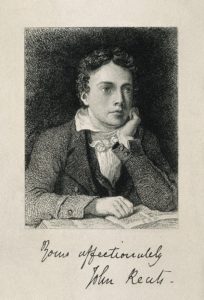

John Keats, the great Romantic poet, also trained as a surgeon-apothecary, at Guy’s Hospital and probably used that very dissecting room. Academics have identified a number of references in his poetry which can be traced to his time on the wards and at his anatomy studies, such as the change in Lamia from serpent to human form and the following chilling fragment.

This living hand, now warm and capable

Of earnest grasping, would, if it were cold

And in the icy silence of the tomb,

So haunt thy days and chill thy dreaming nights

That thou would wish thine own heart dry of blood

So in my veins red life might stream again,

And thou be conscience-calm’d–see here it is–

I hold it towards you.

Keats gave up medicine for poetry, with just weeks to full qualification as a surgeon, because he felt concerned that one slip of the scalpel could kill a live patient. His concern would have made him a better doctor, perhaps. Too many surgeons of the time had used the dissecting room to practice what we would consider butchery rather than surgery.

___________________________________________________________________

Death Disease & Dissection is available in a bundle with Maladies and Medicine from Pen and Sword at a combined cost of just £20.89

Suzie Grogan is a freelance writer with a particular interest in health (especially mental health) and in the poet John Keats. Find out more at www.suziegrogan.co.uk and on her blog www.nowrigglingout of writing.wordpress.com