Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Nearly all of us have grown up hearing about the horrors of the plague. It is common knowledge that, as one early modern pamphlet recorded, ‘The surest token of all to know the infected of the plague, is, if there doe arise and engender botches behind the eares, or under the armeholes’.1 Most children also learn that people attempted to keep the plague (or pestilence) at bay by perfuming the air around them. The same treatise explained ‘It is very good when one goeth abroad, to have something in their hands to smell too, the better to aviode those noisome stinkes, and filthy savors which are in every corner, therefore it is very good to carry in the hand a branch of Rew, Rosemary, Roses, or Camphire’.2

However, there were numerous other remedies suggested for curing the plague. Some of them more interesting than others. Here are two of my favourites.

1. ‘TAke an Oinon [sic], and cut him overthwart, or asunder then make a little hole in each peece, the which ye shall fill with fine Treakle, and set the peeces together againe, then wrap them in a wet linen cloth, putting it as you would a warden, and so roaste him in the embers, seeing it be covered with embers, and when it is rosted enough, straine out all the juice thereof, and give the patient a spoonefull thereof to drinke, and it will heale him by the grace of God.’

Onion juice it would seem was a medical marvel, as we have already seen it was not only a cure for plague but also for male pattern baldness!

2. If there doe a botch appeare.

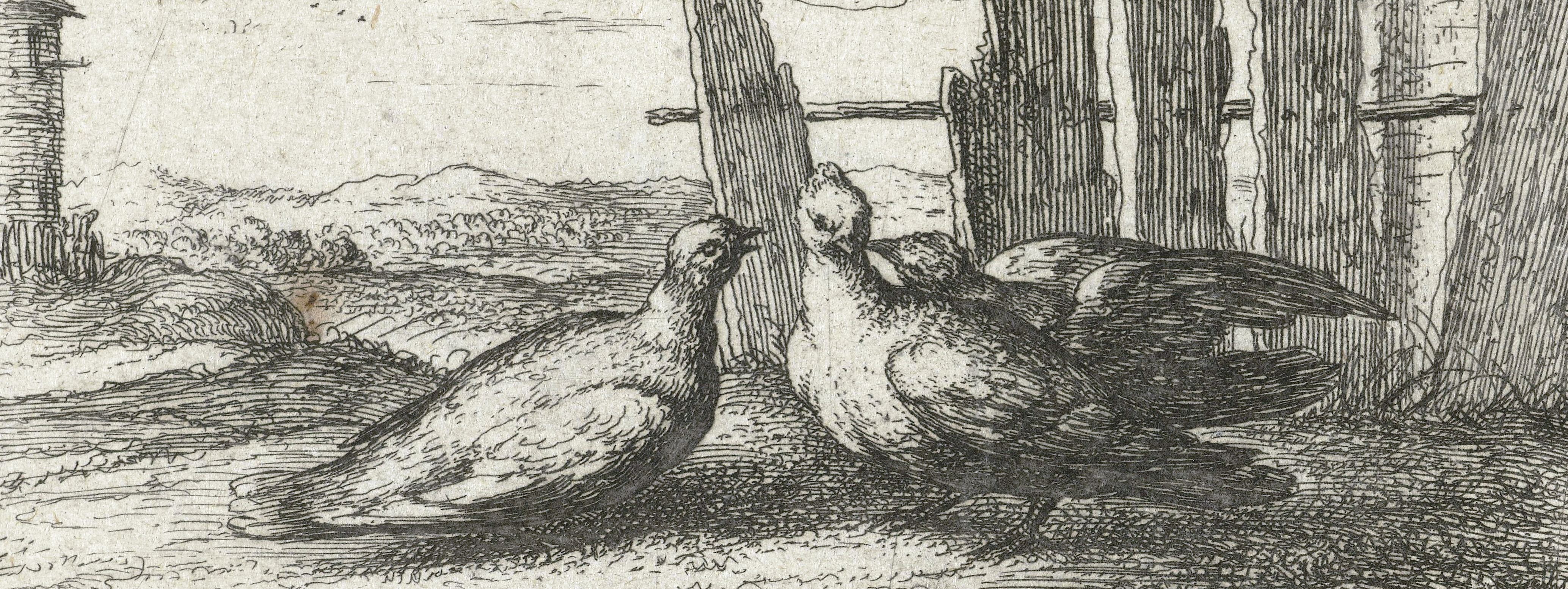

TAke a Pigeon, and plucke the feathers off her taile, very bare, and set her taile to the sore, and shee will draw out the venome till shee die; then take another and set too likewise, continuing so till all the venome be drawne out, which you shall see by the Pigeons, for they will die with the venome as long as there is any in it: also chicken or a henne is very good.

This method was believed to work through transference. The disease left the patient and moved into the body of the pigeon, when the pigeon died the disease was no longer a threat to the patient’s body.

This method was believed to work through transference. The disease left the patient and moved into the body of the pigeon, when the pigeon died the disease was no longer a threat to the patient’s body.

This is perhaps my favourite plague remedy because every time I read it, it conjures visions not only of a collection of sad-looking plague ridden pigeons, but of people trying to hold a half bare bird to their face.

UPDATE! After compiling this post I then read a wonderful article by Martha Baldwin on the use of toad amulets to treat the plague.3 Like the pigeons, toads, as well as their vomit, faeces and urine, were all worn on the body in various amulet forms to ward off and cure the plague. One medical writer Athanasius Kircher was an appropriate remedy because its tuberous skin resembled that of a plague victim who was covered in lesions, spots and buboes.4 Toads were also thought to be relevant because they ate a lot of worms which corresponded to the worms found in the bellies of plague victims.5 If this wasn’t enough Kircher also believed that the toad’s innate hatred (or according to other writers fear) caused the disease itself to hate (or fear) the body of man and so leave.6

UPDATE! After compiling this post I then read a wonderful article by Martha Baldwin on the use of toad amulets to treat the plague.3 Like the pigeons, toads, as well as their vomit, faeces and urine, were all worn on the body in various amulet forms to ward off and cure the plague. One medical writer Athanasius Kircher was an appropriate remedy because its tuberous skin resembled that of a plague victim who was covered in lesions, spots and buboes.4 Toads were also thought to be relevant because they ate a lot of worms which corresponded to the worms found in the bellies of plague victims.5 If this wasn’t enough Kircher also believed that the toad’s innate hatred (or according to other writers fear) caused the disease itself to hate (or fear) the body of man and so leave.6

So you could take you pick, pigeons or toads both very useful for warding off the pestilence!

_________

1. The Plagues Approved Physition (London, 1655).

2. Ibid.

3. Martha R. Baldwin, ‘Toads and Plague: Amulet Therapy in Seventeenth-century Medicine’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 67/2 (1993), 227-247.

4. Ibid, p.237.

5. Ibid, p. 237.

6. Ibid. p. 237.

© Copyright reserved

I have come across a similar recipe in the medical recipe manuscript book I am using for my thesis. I have not yet figured out the significance of the feather plucking. Any ideas?

I assumed it was to allow skin to skin contact to aid transference. But I don’t know for sure. I was reading a wonderful article on toad amulets for plague yesterday and that mentioned the similarities between toad skin and pestilential buboes

Jennifer–I would love to read that article on toad amulets if you wouldn’t mind sharing the reference. Thanks!

Dear Lori, of course the reference is in the footnotes provided

Best Jennifer