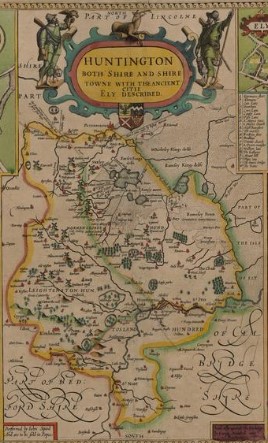

On 28 July 1716 the Huntingdon assizes condemned Mary Hicks for witchcraft. According to the published narrative of her case, Mary lived in Huntingdon with her husband Edward and their 9-year-old daughter Elizabeth. Elizabeth was apparently the ‘Aple of his Eye’.

This picture of domestic happiness shattered when Mary became a witch. She made an ‘impious and wicked’ pact with the Devil, sealing the bond with ‘her own Blood’. Like most witches in the early modern period, Mary used her newfound powers to inflict ‘Torment’ and illness on her neighbours. They began to suffer from fits, ‘strange Pains and Tortures’. Several neighbours were also made to ‘Vomit Pins and Needles’.

In particular, Mary turned her attention to Mr. Adams a neighbour with whom she had quarreled. According to the description published in London that year, she ‘made an Image like him of Wax, which putting on a Spit and roasting before a Fire, as that melted away, so did the Neighbour suddenly waste away by degrees and in 24 Hours died in the greatest Pain imaginable.’

There is nothing particularly unusual in Mary Hicks’ story thus far: a woman was accused of inflicting illness and sickness of her neighbours using diabolical powers gained from the devil. In many early modern discussions of witchcraft people attributed illnesses that were difficult to understand or ascribe to a particular cause – like sudden fits, or apparently fast acting consumption – to witches.

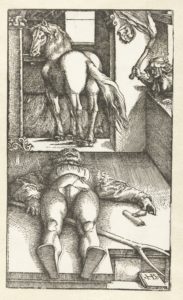

Like other stories of witchcraft, Mary’s used her powers on local livestock as well as her human neighbours. She apparently made ‘Horses Lame, Oxen Sick, Crows bleed to Death at the Fundament [anus], Calves and Sheep Bling, Hogs run Mad’. The author of the pamphlet which tells this tale said these acts were ‘notorious and mischevious Pranks’. The Flowers family who bewitched the Earl of Rutland and his wife in c. 1618 likewise harmed and killed cattle before inflicting infertility and illness on the Earl’s family.

Mary may have continued her wicked ways had she not convinced her daughter to sell her soul to the devil also. Having acquired her powers, one day while watching a ship at sea from a window with her father, the girl demonstrated that she could cause a storm and wreck the ship. She later destroyed an entire field of corn. Edward duly questioned his daughter about where she had gained such abilities. Elisabeth replied that her mother had taught her. Edward sadly then turned over both his wife and his daughter to the Justice of the Peace, and watched as they were hanged for their crimes.

Mary Hicks, like many other women prosecuted for witchcraft in the early modern period, was accused on the basis of a range of medical symptoms appearing in her local community. In this her story is unremarkable, but it is unusual because of when these events supposedly happened. By the early eighteenth century many people questioned the reality of witchcraft. Even the author of this pamphlet acknowledged that many people no longer believed that witches were real.

One of the last women condemned to death for witchcraft was Jane Wenham who was tried in Hertfordshire in 1712. Mary and her daughter, if we are to believe this pamphlet, were convicted and executed four years later. That the author chose to tell her tale suggests that despite scepticism among scholars and some members of the wider populace, there was an audience for this type of narrative, and thus that many people were still convinced that unexplained and sudden illnesses were the result of witches machinations.

_________________________

The Whole Trial and Examination of Mrs Mary Hicks and her Daughter Elizabeth (London, 1716).