Abigail Harley and Brampton Bryan: Making a Medical Commonwealth

By Emma Marshall

How were illness and healthcare entangled with power in the past? Abigail Harley (c.1664-1726) of Brampton Bryan, Herefordshire, was part of a famously political family. As an unmarried, childless younger daughter with little obvious authority, she has often been overlooked. However, her healthcare activities made her a ‘powerful’ figure in her own right.

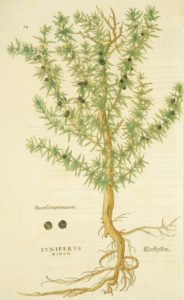

Title page of ‘The English Physitian: or an Astrologo-physical Discourse of the Vulgar Herbs of This Nation by Nicholas Culpeper’, 1652 (Wikipedia)

Medical texts, skills and knowledge were valued and shared across generations of the Harley family. Lady Brilliana sent advice and substances such as ‘juce of licorish’ and ‘a glass of eye water’ to her son Edward Harley when he was a student at Oxford in the 1630s.[1] Later letters from Edward to his wife Abigail Sr. mention multiple ‘folio receipt books’, homemade remedies stored at Brampton Bryan, and his sending of medicines such as ‘Gascoins powder’ and ‘Epidemic Water’ from London to Herefordshire.[2] In 1669, Abigail Sr. asked Edward to buy her Nicholas Culpeper’s popular herbal, ‘that we had here that was my brother Stephens’, as a New Year’s gift.[3] This gives some insight into the familial culture of interest and expertise in healthcare in which Edward and Abigail’s daughter, also Abigail, grew up.

Abigail Sr. died in 1688 and Edward was elected as MP for Herefordshire in 1693, spending much time in Westminster. Abigail Jr., aged in her twenties, took on her parents’ role and oversaw the health of her siblings, nieces and nephews, servants and neighbours, regularly reporting her medical activities to Edward in letters. She produced and administered treatments such as ‘a Lambative made up with woodlice’, ‘red balsame’, ‘a diet drink’, ‘the powders my mother used’ and ‘Lucatellas Balsam which a great many want’ to her household, often noting successful outcomes.[4] Medicine-making wasn’t her only task; Abigail also monitored quality of sleep, breathing, temperature and bodily excretions of sick household members. She expressed confidence in her own medical abilities but also anxiety for Edward’s assistance and approval, often requesting ‘advice’ and ‘direction’ and deferring to his judgement after providing relevant information.

In July 1696, Abigail reported the illnesses and treatments of Edward’s ‘old servants’ John Hagley and Hugh Rowland and asked his permission to send venison to Maurice Lloyd, rector of St. Barnabas church on the Harleys’ estate, when he was ‘very ill’.[5] Venison is an ancient and symbolic gift, traditionally given by elites to their dependents in local networks of reciprocity. She also gave Lloyd and Alexander Clogie, minister at another of the Harleys’ patronised churches in nearby Wigmore, ‘powders’, ‘medicine’ and ‘cypris wine’ during sickness. Abigail obtained these from her father in London, and conveyed the clergymen’s ‘humble service & thanks’ for the ‘great kindness’ back to Edward.[6] Other examples of her care for local subordinates include asking the family’s doctor to attend ‘J. Carter’, probably a servant or neighbour, during a serious illness in May 1694, and a few weeks later allowing one Mr Davis, ‘struck all one side wth ye Palsey’ whilst labouring, to borrow a coach to travel home in.[7]

Abigail’s medical assistance of her social inferiors was an important, empowering form of patronage. The early modern parish was a unit of hierarchy and order, and the Harleys exchanged medical goods and services in return for deference and loyalty, which contributed to social stability in Brampton Bryan. The family and parish’s recent history made Abigail’s activities in the 1690s particularly important. Royalist sieges during the Civil Wars had led to the ruin of Brampton Bryan’s castle and church, and the death of Abigail’s respected grandmother, Brilliana.[8] Local political support for Edward fluctuated wildly before his re-election as MP in 1693, and his position remained unstable; Abigail’s brother Robert was assaulted by enemies in New Radnor, close to Brampton Bryan, in 1693.[9] Additionally, Edward’s time in London strained the personal bonds with social inferiors which validated his status as lord of the manor.

Brampton Bryan Hall (Wikimedia Commons)

In this context, Abigail’s healthcare activities were not simple acts of love or charity, and their description in letters was more than the practical exchange of news. They were also ‘political’ strategies, structured by family power dynamics and local tensions. Abigail’s medical practices helped to negotiate her relationship with her father, to construct her identity as manager of his household in his absence, and to consolidate the Harleys’ fragile authority within their rural community. Her letters challenge our understanding of the connection between health and power. Identities and relationships within household and parochial ‘little commonwealths’ could be shaped through everyday healthcare practices.

Emma is a PhD student at the University of York’s History Department, where she is funded by the Wolfson Foundation and supervised by Dr Mark Jenner. She explores how sickness and healthcare intersected with power dynamics, identity, and ideas of order and authority within early modern elite households. Her primary sources are familial letters, alongside wills, household accounts, recipe books, and autobiographical writings. Her wider research interests include gender, domestic life, medicine and the body, and she has previously written dissertations on seventeenth-century women’s medical recipes and marital conflict in church courts.

- Letters of The Lady Brilliana Harley, Wife of Sir Robert Harley, of Brampton Bryan, Knight of the Bath, vol. 58 (London: Camden Society, 1853), p. 5 (Lady Brilliana Harley to her son Edward Harley, 13 Nov 1638) and pp.36-8 (Lady Brilliana Harley to her son Edward Harley, 29 Mar 1639).

- British Library (BL), Add. MS 70128 (Sir Edward Harley to his wife Lady Abigail Harley, 9 Nov 1680)

- BL, Add. MS 70115 (Lady Abigail Harley to her husband Sir Edward Harley, 30 Nov 1669)

- BL, Add. MS 70116 (Abigail Harley to her father Sir Edward Harley, 10 May 1692, 18 Jan 1693, & 24 April 1694); BL, Add. MS 70117 (Abigail Harley to her father Sir Edward Harley, 12 June 1697 & 6 July 1697)

- BL, Add. MS 70117, (Abigail Harley to her father Sir Edward Harley, 8 July 1696)

- BL, Add. MS 70117, (Abigail Harley to her father Sir Edward Harley, 25 May 1697)

- BL, Add. MS 70116, (Abigail Harley to her father Sir Edward Harley 1& 22 May 1694)

- https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/heref/vol3/pp19-21; https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/12334

- Edward Rowlands, ‘The Harleys and the Battle for Power in Post-Revolution Radnorshire’, Welsh History Review, Vol. 15, 1 (1990), 21, 26, 32.