A guest post by Jo Willett

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lady_Mary_Wortley_Montagu#/media/File:Liotard_Lady_Montagu.jpg

As the Coronavirus crisis continues, seemingly daily we get news of the scramble to find a vaccine and ineffective antibody tests. Today we have a guest blog by Jo Willet pointing out the parallels between the search for a vaccine for this new virus and the one pioneered in the eighteenth century to end the scourge of small pox.

Volunteers are the key to clinical trials and perhaps the most famous historical example is Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s decision to inoculate her own 3-year-old daughter, using a tiny amount of smallpox pus. The experiment took place in Twickenham in 1721, during a lock-down very like ours today.

Travels in Turkey

Lady Mary had observed inoculation when she was living in Turkey as wife to the British Ambassador. In March 1718, while her husband was absent, she had their only son inoculated. The previous ambassador had protected his sons in the same way, so in Turkey Lady Mary was just following a trend.

She wrote a detailed description of the process to her childhood friend, Sarah Chiswell, whom she’d failed to persuade to accompany her to Turkey. Doctors would resist introducing it back home in England, she predicted, and she anticipated she’d have to ‘war with ’em’.[2]

‘Every year thousands undergo this Operation […] I am very well satisfy’d of the safety of the Experiment since I intend to try it on my dear little Son. I am Patriot enough to take pains to bring this useful invention into fashion in England.’

(The Complete Letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, edited by Robert Halsband, (OUP, 1965), Vol 1, p. 339).

Lady Mary’s daughter was only a baby at that time. Her Armenian nurse had never had the disease. Mary concluded – correctly – that the un-inoculated nurse would be likely to catch it from her inoculated baby daughter: that inoculated smallpox was still contagious. So, she decided against having the procedure performed on the girl at that time.

Return to England

When Mary returned home to England, she found that the smallpox epidemics there were becoming more frequent and more severe. Unlike in Turkey, the virus was raging unchecked. During the outbreak of 1719 Mary kept quiet. She knew her unprotected daughter was vulnerable, but she didn’t dare take action.

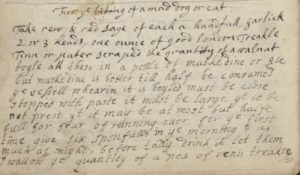

Copyright Hugh Matheson.

Trials during lock-down

But in 1721, shut up in her house in Twickenham during yet another outbreak, Lady Mary did decide to conduct her own version of a clinical trial.She summoned Dr Charles Maitland, a surgeon, who had accompanied her to Turkey. Maitland was nervous at the prospect, but eventually he bent to Lady Mary’s iron will.

He was sent out to collect smallpox pus from a neighbour suffering from the disease. Together Lady Mary and Maitland then pressed it into the wounds they had opened on the little girl’s wrists and ankles. Ten days later Mary’s daughter started to run a fever and a few spots broke out on her skin.

Lady Mary then arranged for a form of peer review consisting of ‘Several Ladies and Other Persons of Distinction’.[3] The mother stood protectively in the doorway while her guests examined her daughter’s spots, checking her forehead for a fever. One of these – a physician named Dr James Keith – asked that they inoculate his own, only- surviving son, Peter.

Lady Mary understood that there was no need to add to the treatment with medical procedures like bleeding and purging the patient. But the two doctors did bleed and purge young Peter Keith. He survived the ordeal and became the second successful example of inoculation in the West.

Amateur scientist, Lady Mary, had correctly worked out that the Turkish method could be used to mitigate the extensive outbreak of smallpox in England. She also understood that there was no need to medicalise the process more than necessary with extra interventions. Just as Lady Mary had predicted, the medical establishment initially resisted inoculation. Inevitably doctors only agreed to it, if they could bleed and purge as well. Lady Mary’s analysis was that this ensured they could continue to charge fees.

It was Edward Jenner’s bad experience of this process, which led him later in the century to take the intellectual leap to vaccination rather than inoculation as a cure for smallpox, using more controllable infected material from cows rather than humans.

Reception

As for Lady Mary, after her experiment she spent her time travelling between friends’ households, inoculating whoever asked for her help- masters and servants alike. Her daughter – who often travelled with her – remembered the ‘looks of dislike’ that often greeted them and the ‘significant shrugs’ from sceptical bystanders.[4]

However, Lady Mary admitted that nearly every day for the rest of her life she regretted putting the process in motion. As she put it: ‘what an arduous, what a fearful and, we may add, what a thankless enterprise it was.’[5] Her erstwhile friend, the poet Alexander Pope, vilified her in writing for her contribution, deliberately linking her not to ‘smallpox’ but to ‘pox’ – venereal disease.

As a footnote to the story it is perhaps worth noting that Lady Mary’s childhood friend Sarah Chiswell, who did not go on the Turkish travels, herself refused to be inoculated. She died from the disease in June 1726.

Jo’s biography The Pioneering Life of Mary Wortley Montagu: Scientist and Feminist is due for publication in April 2021 (the 300th anniversary of Mary’s inoculation experiment in Twickenham), published by Pen & Sword Books. Jo has been an award-winning tv drama and comedy producer all her working life. She studied English at Queens’ College Cambridge and has an MA in Arts Policy. Twitter @Willettjo

[1] Jenkins, Jean and Hubbard, Susan ‘History of Clinical Trials’ in Seminars in Oncology Nursing, Vol 7, Issue 4 (Elsevier, 1991).

[2] Halsband, Robert, (ed.), The Complete Letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, (OUP, 1965), Vol 1, p. 339.

[3] Maitland, Dr Charles, An Account of Inoculating the Smallpox (London, 1722), p. 10.

[4] Halsband, Robert & Grundy, Isobel (eds.), Essays and Poems and Simplicity a Comedy (Clarendon, Oxford, 1977), p. 36.

[5] Halsband, Robert & Grundy, Isobel (eds.), p. 35.