By Dr Sara Read

According to the case notes of Dr John Woodward (1665-1728), at around the age of fifteen a Mrs King (b. 1675) had a piece of wood fall on her which resulted in an open wound on her leg.[1] At the time, Mrs King was not long recovered from a catalogue of diseases ranging from a year-long cough, extreme constipation, to the measles. The wound became ulcerous from her knee to her ankle, which the doctor blamed on entrusting her case to a local woman, rather than calling in a surgeon. The surgeon, a Mr Knowles, managed to effect a cure of sorts. The remarkable thing about this case is that six months after the surgeon had begun to heal the wound it still bled on a monthly basis. The marginal notes to the publication of these case notes describe this monthly bleeding as a ‘Menstrual Haemorrhage at the Ulcer for Two Years’. The notes suggest the ulcer discharged a similar amount of blood as the woman could expect to void at a normal menstrual period. Three months after the surgeon managed to get the wound to heal properly, King’s periods began and continued regularly until after she was married and began to ‘breed’.

John Woodward’s case notes are extremely long-winded and even his eighteenth-century editor remarks that ‘he is sometimes tedious in his Narration, and the material Parts might have been contracted in a narrower Compass’ (p. iv). However, the pattern of Mrs King’s bouts of illness all result from the same cause which is her failure to void her excess humours.

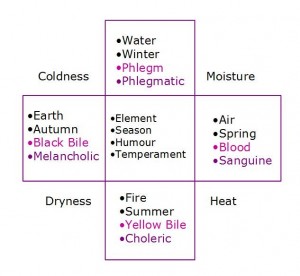

‘Humours’ was the name given to all bodily fluids at this time, and there were thought to be four main humours: blood, bile, phlegm, and melancholy (or black bile). Each humour was related to the seasons of the year and also to the four elements. The composition of male and female bodies was thought to be different in terms of humoral balance too. A disproportion of any one of these humours was thought to be the cause of bodily illness. The medical notes of Mrs King note that she is regularly constipated and doesn’t begin her periods until she is at least seventeen, if the case notes are accurate, since she bleeds at the leg ulcer for two years instead. It was normally expected that girls began to menstruate around the age of fourteen, so that she would have a build-up of excess blood that would find a passage out of the body in this way, if for any reason it couldn’t come from her womb, now that she was of age.

The medical notes of Mrs King note that she is regularly constipated and doesn’t begin her periods until she is at least seventeen, if the case notes are accurate, since she bleeds at the leg ulcer for two years instead. It was normally expected that girls began to menstruate around the age of fourteen, so that she would have a build-up of excess blood that would find a passage out of the body in this way, if for any reason it couldn’t come from her womb, now that she was of age.

This typifies the early-modern paradigms about health being controlled by a finely tuned humoral balance. Since Mrs King had a build up of humours which she seemed unable to void by conventional means, such as opening her bowels or menstruating, her excess, corrupt humours took the opportunity to egress from the easiest alternative means, in this case an open wound on her leg. This explanation entirely fits in with the early-modern medical models which claim that women’s bodies are colder and wetter and generally less efficient than the male equivalent and so need to bleed as they are unable to use up all their blood like more vital, active men were thought to do. However, vicarious menstruation wasn’t something which was thought to happen to women: ill men who had piles or regular nosebleeds were often described as having a ‘menstrual’ bleed.[2] These diagnoses emphasise that maintaining a balance in the body was thought not only the best way of curing most illnesses, but also what a body would be trying achieve for itself, by taking any opportunity to void excess blood which wasn’t used up in normal activity.

For another case of vicarious menstruation through an ulcer see Lisa Smith’s on a menstruating tongue ulcer discussed in the Sloane Letters. http://www.sloaneletters.com/unusual-case-of-menstruation/

Dr Sara Read is a teacher in the department of English and Drama at  Loughborough University, England. She currently holds a Post-doctoral Fellowship from the Society for Renaissance Studies. Sara is co-editor, along with two colleagues, Rachel Adcock and Anna Warzycha, of an anthology of seventeenth-century women’s writing which is being published by Manchester University Press in 2013. Sara has an article in Issue 2 of Discover Your Ancestors published in February 13 on the topic of using medical casebooks such as those of Dr Woodward as a genealogy aid.

Loughborough University, England. She currently holds a Post-doctoral Fellowship from the Society for Renaissance Studies. Sara is co-editor, along with two colleagues, Rachel Adcock and Anna Warzycha, of an anthology of seventeenth-century women’s writing which is being published by Manchester University Press in 2013. Sara has an article in Issue 2 of Discover Your Ancestors published in February 13 on the topic of using medical casebooks such as those of Dr Woodward as a genealogy aid.

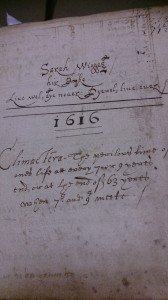

[1] John Woodward, Selected Cases in Physick, ed. by Peter Templeton (1757), p. 1.

[2] Gianna Pomata, ‘Menstruating Men: Similarity and Difference of the Sexes in Early Modern Medicine’, in Generation and Degeneration: Tropes of Reproduction in Literature and History from Antiquity through Early Modern Europe, ed. by Valeria Finucci and Kevin Brownlee (London: Duke University Press, 2001), pp. 109-52.

© Copyright Sara Read. All rights reserved.

5 thoughts on “Mrs King of Northfleet’s Menstruating Leg Ulcer.”

Comments are closed.