Medical texts in the early modern period included much material that modern readers may not consider medical. They often included remedies for making the skin clear and blemish free or for removing excess and unwanted facial and bodily hair. Peter Leven’s medical treatise also offered a range hair dyes. In particular he offered several recipes to make the hair ‘yellow’, or blonde.

The first was as follows,

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

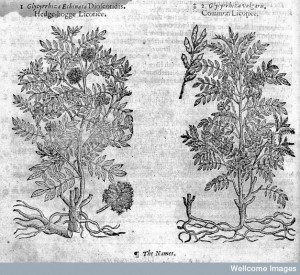

‘Take the best and the strongest lye that can be made, then take a good handful of red Fennell, of Margerum as much, of Sage a handful, Violets as much, of Damaske Roses a handful, of Red Roses as much, two Nutmegs, of Cloves & Mace one ounce of each, Enula Campana, as much, Drice powder, as much, Licorice two or three sticks sliced, a handful of Lavender spike, and let the lye stand nine dayes, and then straine it, and seeth it one wane, and scum it, then put al the hearbs and spices there in, and so occupie it when you thinke good, with a spunge wet your haire, and then let it dry in of it selfe: this will keepe your head from aking, and make your haire as yellowe as golde.’1

This was a dual remedy which prevented headache and made the hair the colour of gold. Now a modern reader might assume that these remedies were intended for a predominantly female audience. However, Levens included one recipe which he claimed to have used himself quite often:

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

‘Take the rinde or barke of Rubarbe, and take the scraping thereof, and steepe it in white wine, or cleere Lye, and after that you have washed your head therewith, you shal wet your haire with a Sponge, or some cloth kept for that purpose, then let your haire dry against the fire or sunne, and the oftner that you use it, the better it will prove, as I have often tried.’2

Hair colour was not simply a frivolous matter of fashion, though. Hair colour revealed something about the body to the outside world. Medical writers, like Isbrand van Diemerbroeck, explained that hair colour varied according to the humoural make up of the body. Cold phlegmatic people were thought to have white hair. If ‘Smoaky Vapors’ were mixed with this the hair would be black. Those who had hot constitutions that concocted their food well were also thought to have black hair. Bodies dominated by choler would be red haired.3

Diemerbroeck didn’t mention blonde hair specifically in his description, but did explain that hair colour, through the constitution, was also connected to national identity. He noted that, ‘the Egyptians, Arabians, Indians, Spaniards and Italians are generally black-hair’d; because they inhabit hot Countreys, and are us’d to strong Wines, and other hot Diets’.4 Thomas Bartholin agreed, and further noted that ‘They who dwell in cold and moist Coutnries, have their hairs not only soft and straight, but for the most part yellow or white, as the Inhabitants of Denmark, England, Swedland, Scythia, &c.’5 Temperate bodily heat, he suggested, made the hair yellow. This was perhaps then the most desired colour because it signified moderation of bodily heat.

The diversity of bodies thus allowed for a diversity of hair colours, but Bartholin was careful to note that these weren’t unlimited: ‘But no Hairs on the Body of Man are Naturally green, or blew, though there are both green and leek-colour’d Choler in Mans Body.’6

Hair colour then was more than just a fashion statement, it revealed to the world details about your bodily composition and humoural complexion. These in turn were connected to personality, so in some ways your hair could reveal who you were.

___________________

1. Peter Levens, A Right Profitable Booke for all Diseases called, The Path-way to Health. Wherein are to bee found most excellent and approved Medicines of Great Vertue … (London, 1632), Sig. A3V

2. Ibid. * Lye is described by the OED as Alkalized water, primarily that made by the lixiviation of vegetable ashes, but also applied (esp. with prefixed word as in soap-lye, soda-lye) to any strong alkaline solution, esp. one used for the purpose of washing, or more generally as detergent. In a secondary sense as a cosmetic for the hair.

3. Isbrand van Diemerbroeck, The anatomy of human bodies (London,1694), p.377.

4. Ibid.

5. Thomas Bartholin, The Bartholinus Anatomy, p.129.

6. Ibid.

© Copyright Jennifer Evans, All rights reserved.

This puts me in mind of the conversation between Celia and Rosalind in *As You Like It* 3.4, where they discuss Orlando’s hair colour.

Rosalind says he is untrustworthy because his ‘very hair is of the dissembling colour’. Celia replies that in fact it is ‘something browner that Judas’. This is because Judas was always depicted as having red hair and this hair colour attracted a lot of prejudice in early modern Europe. Rosalind is cheered up by Celia’s comments and replies ‘I’faith, his hair is of a good colour’. In fact as Celia points out his hair is the same colour as Rosalind’s which they decide is chestnut ‘your chestnut was the only colour’.

So the couple are well matched humorally as well as socially in rank, etc (even though they don’t know this yet). As you say, hair colour carried a whole world of significance at this time!

Sara

That depends, of course, on how one defines ‘medicine’ or ‘medical’. I’d argue that ‘medical history’ encompasses a vast range of issues relating to beliefs, practices and perceptions of ‘health’, illness or physical and/or mental wellbeing.

I would agree, but I think this is something that surprises those who have not looked at health and wellbeing in the past.