A guest blog post by Dr Shona McIntosh

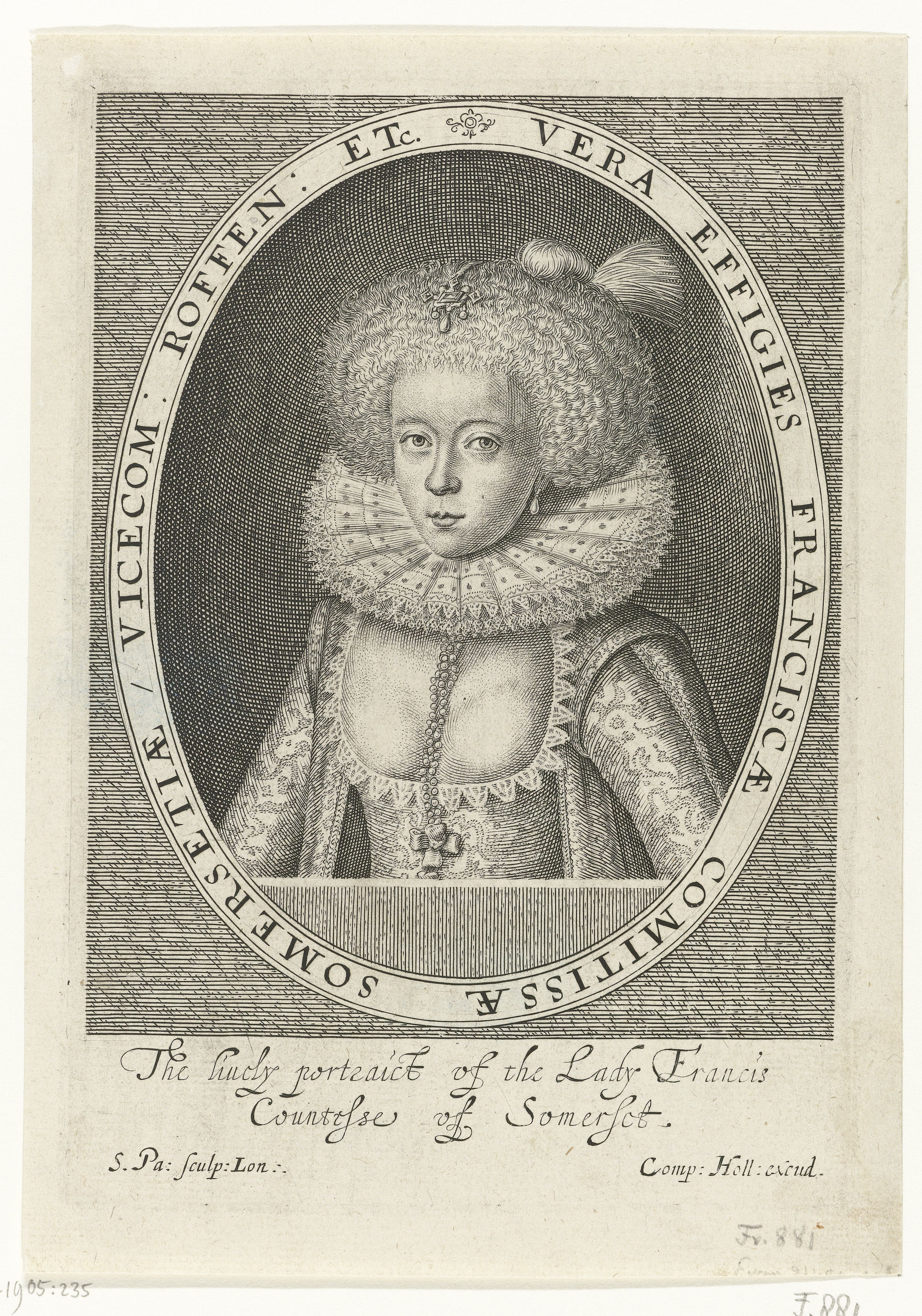

Frances Howard’s marriage to the Earl of Essex is one of the most famous instances of marital dysfunction in the early modern period. Ballad-makers enthusiastically commented on the ‘strange frigidity’ which was detailed in Frances’s petition for annulment in 1613. The judges also found the charge a somewhat ‘strange’ one: unlike either of the two legal precedents cited, the petition stated that the Earl was impotent only with his wife – impotentia versus hanc.1 No cause was officially suggested for this selective impediment, but the panel seems to have assumed it was witchcraft or maleficium.2

From the early days of divorce in canon law, Angus McLaren writes, ‘a long line of celibate church doctors found themselves debating the finer points of such subjects as erection, penetration, and emission in their efforts to spell out how to determine if consummation had occurred.’3 Archbishop Abbot, who led the commission, describes how they had attempted to clarify the mechanics of Essex’s condition in this way, but had received no satisfactory response: ‘which although they were then smiled at, and […] much sport had been made […], yet now our married men on all hands wish that punctually his lordship might have been held to give his answer unto them.’ Essex refused the judges’ requests that he appear in person, instead submitting a distinctly evasive document. In this, he states: ‘he never carnally knew [Frances], yet knew not any defect in himself, but was not able to penetrate into her womb and enjoy her. […] He believeth not that the said lady Frances is a woman fit and able for carnal copulation because he hath not found it.’

It seems to me that Essex suggests here that it is Frances, not himself, who is impotent. Female impotence, Pierre Darmon describes, was known to the French divorce courts, which saw a much larger volume of divorce cases in this period. Darmon describes the symptom of ‘arctitude’, or a vagina too narrow to penetrate, as well as membranes or other obstructions in the womb that might be classed as female impotence.4 An English pamphlet of 1678 also refers to ‘Impotency in the women, termed Arctitude in the Law.’5 By dodging the questions of erection, penetration, and emission which the judges wish him to answer, and suggesting instead that Frances’s body is obstructing his attempts, Essex in effect reverses the charge of impotence.

One of the initial questions the panel raised was ‘whether my lord of Essex would be inspected by physicians to certify the true cause and nature of the impediment.’ However, what then ensued was an inspection of Frances, to determine whether she was ‘fit and able for carnal copulation’ and ‘a virgin carnally unknown by any man.’ A bed-trick of sorts seems to have been played, the wife’s body substituted for the husband’s. David Lindley establishes that the reason the Earl was not inspected was that he would not agree to it 6, and Daniel Dunne, (one of the commissioners) wrote afterwards: It was desired by the counsel of the said lady that matrons should make an inspection of her body’.7 So it was Frances, or her lawyers, who moved to have her body inspected. The midwives and matrons duly found her ‘a virgin uncorrupted’ and ‘apt to have children’, with the State Trials stating coyly that their ‘secret reasons’ for this ‘were not fit to be inserted into the record.’ This effectively destroyed Essex’s accusation against her, throwing the panel back to his inability, and their speculation as to the real cause and nature of it. Was the information they currently possessed sufficient grounds for the annulment?

They could not agree. Abbot was particularly sceptical. He did not believe in maleficium, for one thing, calling it a ‘concomitant of darkness and popish superstition,’ and suggesting that the Earl’s answer only proved ‘lack of love and not want of ability’ towards his wife. He even continued to entertain some doubt as to whether Essex was impotent at all. In his later account of his scruples, he cites a rumour that Essex, ‘having five or six captains and gentlemen of worth in his chamber and speech being made of his inability, rose out of his bed and taking up his shirt did show to them all so able and extraordinarily sufficient matter, that they all cried shame on his lady.’ This is evocative of the sort of inspection that Darmon describes French courts ordering defendants accused of impotence to ‘present an erection in their [i.e., a court officer’s] presence, to judge in this manner any defect of the inner parts.’8 Although Essex refused a court-appointed inspection, Abbot seems to treat this story as a substitute.

Ultimately, Abbot’s continued objection to the nullity, if we take his own word for it, was due both to the lack of proof of the Earl’s impotence, and to his incredulity about maleficium as a purported cause. He describes how the Bishop of Winchester (who voted for the annulment) also ‘denied maleficium’, and when Abbot questioned him about how he could then account for the Earl’s selective condition, ‘that he held it a natural impotency which was before the marriage.’ It thus seems that for other commissioners, the witchcraft explanation was also unconvincing, but this did not fundamentally alter their opinion on the case.

Many readers will be familiar with the outcome of the suit: after the panel could not agree, James appointed two additional bishops and told them to break for the summer. On reconvening in September, Abbot and others were still keen to put the Earl to further questioning, but the king was by this point so impatient that the matter be resolved, that he refused to allow it. Abbot’s description of this part of the case also contains the fascinating admission that the panel discussed the possibility that ‘a time [should] be assigned by the judge whether they might carnally know one another’.9 As far as I know, trial by congress has never been used in England, and so the evidence here that it was seriously debated in this case is surely worthy of remark.

The case was eventually settled by a majority vote in Frances’s favour. Abbot and four other commissioners left the court before the verdict was read, in protest at the decision. The divisions between the commissioners, although they were undoubtedly influenced by the highly charged political atmosphere around the case, were in large part due to diverging opinions about what constituted impotence and what would provide a satisfactory proof of the condition.

Dr Shona McIntosh studied English Literature at the University of Glasgow, where she first discovered her affinity for all things early modern. She completed a PhD on the drama of George Chapman, and taught English at the Universities of Glasgow and Exeter. She now lives in Edinburgh and coordinates the University of Glasgow Summer School. She is writing a novel about Frances Howard.

Dr Shona McIntosh studied English Literature at the University of Glasgow, where she first discovered her affinity for all things early modern. She completed a PhD on the drama of George Chapman, and taught English at the Universities of Glasgow and Exeter. She now lives in Edinburgh and coordinates the University of Glasgow Summer School. She is writing a novel about Frances Howard.

________________

1 All quotes from the trial, and Archbishop Abbot’s account of it, are taken from Cobbett’s Complete Collection of State Trials, 1822, vol. 1, pp.785-862.

2 David Lindley, The Trials of Frances Howard, Routledge 1993, pp.97-102; Jennifer Evans, Aphrodisiacs, Fertility and Medicine in Early Modern England, Boydell & Brewer 2014, pp.152, 156-7.

3 Angus McLaren, Impotence: A Cultural History, Chicago UP 2007, p.31.

4 Pierre Darmon, Trial By Impotence, Chatto & Windus 1985, p.36.

5 John Godolphin, Repertorium Canonicum or an Abridgement of the Ecclesiastical law of the realm, consistent with the temporali, London: 1678, p.493. Early English Books online, accessed 26/10/15.

6 Lindley, p.100.

7 Anne Somerset, Unnatural Murder: Poison at the Court of James I, Weidenfield & Nicolson 1997, p.123.

8 Darmon,.p.175.

9 ST 824.

I worked on a similar topic in Chapter 1 of my book, “The Prince’s Body: Vincenzo Gonzaga and Renaissance Medicine” (Harvard UP, 2015). It involved the unconsummated marriage, due to the wife’s “impotence,” of Vincenzo Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua. Quite an interesting subject indeed!