Writing in his autobiography Sir Simonds D’Ewes explains that on the 22 February 1631 his father, Paul Dewes a barrister and government official,

‘fell sick of a fever, joined with a pleurisy, of which disease he lingered three weeks before he deceased, during which time I had many sad and heavy journeys to him.’1

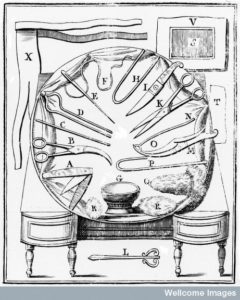

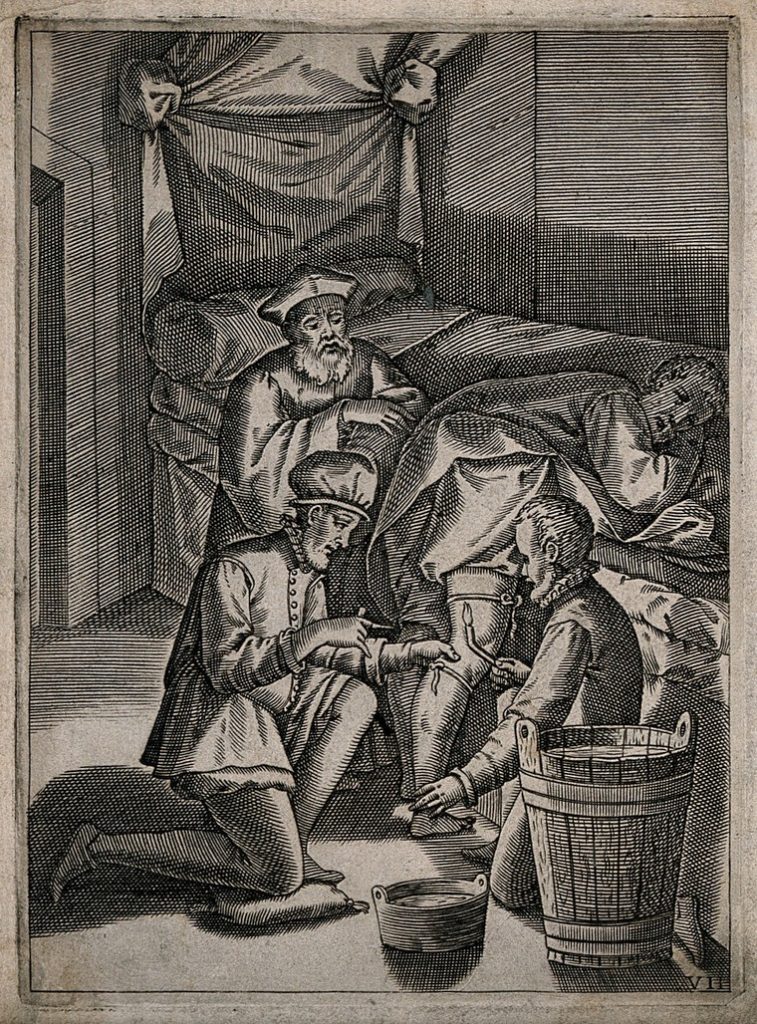

Simonds was a scholar interested in historical and legal antiquities, and a member of the Long Parliament looking to reform both Church and State. His description of his father’s decline and eventual death reveals the repeated use of bloodletting to try ease the condition. This is the only remedy that Simonds records in his narration of his father’s death. We have discussed bloodletting before on the blog (With Stephen Curtis exploring phlebotomy treatises and Sara describing the case of the Blundells preemptive purges) but this story again demonstrates the centrality of bloodletting to early modern medical practices.

Pleurisy

Walter Bruele, the German medic, explained in his book, published just one year after Paul’s death, that pleurisy was an inflammation of the ‘thinne & small skinne’ that enclosed the ribs. He described how the condition caused a continual fever, difficulty breathing, a vehement cough, and ‘a kind of pricking paine’. The cough, he said, started dry but would soon bring up spittle followed by ‘greater store’ of ‘red, and bloody, sometimes yellow’ matter.2 He also explained that pleurisy hurt more in the evenings. As the disease progressed the patient might seep corrupted blood from an imposthume (abscess) or they might spit corrupt blood. All the pre-existing symptoms would worsen and then a redness would break out on the face, accompanied by anxiety and thirst.

It was caused by the season of the year, age, and diet which caused the body to breed too much blood. This blood moved from its proper place in the hollow vein to affect the thin veins in the ribs. That the disease was seen in Autumn and in places with cold air revealed that it was often caused by ‘phlegmy blood’.3

Bruele recommended that pleurisy patients be fed meat of easy digestion including ‘Hens broth … and Almond milke’. At the start of the disease they could also eat raisins, almonds, sweet apples, and endive. He explained that ‘A veine must bee opened, and if necessity require, at midnight’. If the fever was acute and the patient was in extreme pain. When in better health blood was to be let from the Basilica vein (a large superficial vein in the upper arm).

Bloodletting

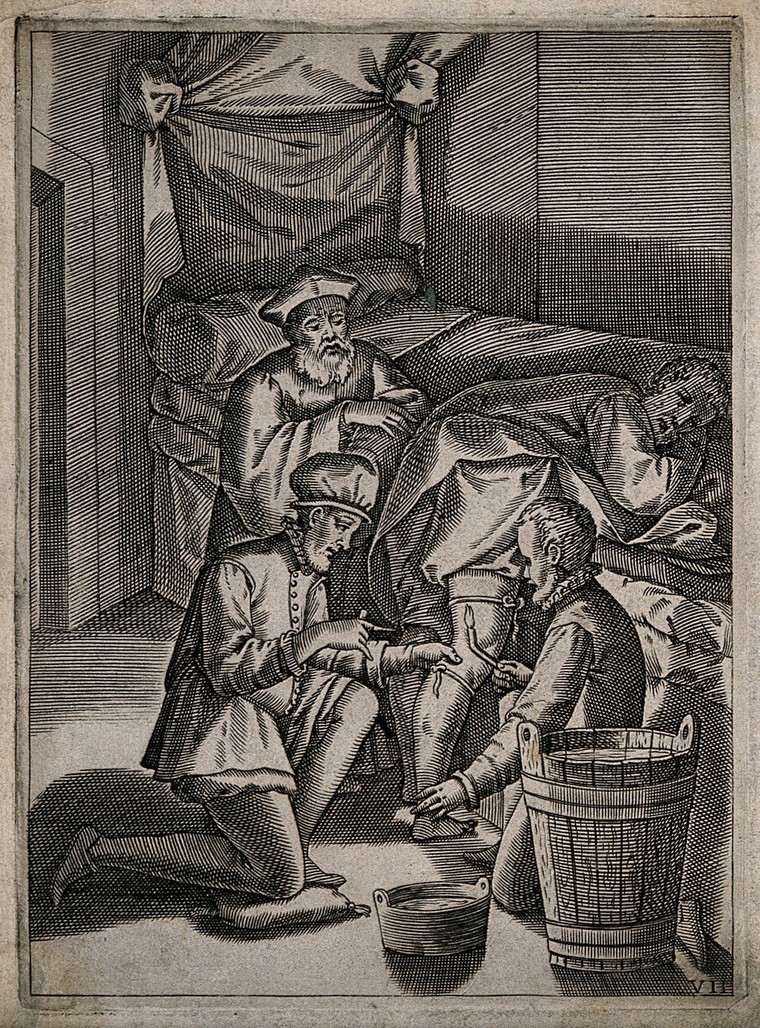

The physicians treating Simonds’ father followed similar advice. Dr Giffard and Dr Basherville visited Paul Dewes ‘twice each day he lay sick’. Between the 22nd and 26th of February he was let blood twice by which ‘he found some ease’. The physicians then ‘open[ed] a vein again on Saturday, the 26th of February, in the morning’. His health not recovering he was let blood again on the 1 March.

Simonds noted that after each bleeding his father felt better, and that he ‘never saw worse nor more infected blood come from any man, so as, had not that which remained been tainted likewise, we might have hoped the loss of so much corrupted blood would have made a way to his speedy recovery.’

Unfortunately for Paul, his case ‘grew more desperate’ and at this point his doctors did not dare to try and bleed him again. They feared he had already lost too much blood for a man of his age. At this point, Simonds recalls, his father developed a ‘most sharp and irksome soreness of his mouth’, which he noted was ‘the fatal forerunner of death many times’. Still his father’s cheery disposition and ease meant that they never dreamed that he would die.

It wasn’t only his father’s ease, that gave Simonds hope. He believed that his fathers good -temperate- diet and his, previously evident, strong constitution showed that he was strong enough to survive the condition. He noted that his father usually suffer two or three times a year with an ague or short fever and these posed him no difficulties.

For his father’s part, Simonds claimed that his father died a good death. He prepared his soul, particularly by amending his heart which had always before ‘been too much set upon the business and profits of this present life’.4 He was unafraid of death during his sickness and showed ‘admirable patience’ during bouts of pain. He developed a clear ‘inward comfort and resolution to die.’

A last bloodletting

Despite having stopped his bleeding treatments earlier, at this point Paul was bled again by the surgeon. Simonds wrote that the surgeon stopped sooner than explaining that he was ‘afraid to take too much blood’. Paul replied ‘Thou needest not’, ‘for what thou leavest will shortly be in the grave’. 5

Paul’s predictions were accurate. Simonds received word on the 14 March that his father was fading. He rushed to be by his side but found his ‘quick and bright black eye […] settled in his head, and all sense and understanding past and gone.’ He recorded that his father suffered terrible pains and sufferings between life and death.6 Paul’s suffering ended for good later that day with his death.

________________________

- The Autobiography and Correspondence of Sir Simonds D’Ewes, Bart. (1845), p. 5.

- Walter Bruele, Praxis medicinæ, or, the physicians practice (London, 1632), pp. 186-7.

- Ibid. p. 187.

- The Autobiography and Correspondence of Sir Simonds D’Ewes, Bart., (1845), p. 7.

- Ibid. p. 8.

- Ibid. p. 9.