Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

This week’s post discusses the case of 20-year-old Anne Taylor, who worked as a servant to a brewer named Sikes, in Romford, Essex. Anne was treated by chemical physician George Thompson (1619-1676) in February 1655. We last met Thompson in this post. Thompson added an appendix to his 1665 book Galeno-pale: A Chymical Trial of the Galenists describing her treatment and recovery. He subtitled the appendix ‘De Litho-Colo: or, An History of Three large STONES excluded the Colon by Chymical Remedies’ in a nod to ‘lithotomy’ or cutting for the stone operation that we have described in previous posts about Samuel Hartlib and watching surgery.

In appearance Anne was ‘of a florid ruddy colour, having a square Body, Vivacious and Active, but low in stature’. Her symptoms included a high temperature, stomach ache, and bloating along with many other things. The doctor concluded that these symptoms were originating from Anne’s spleen. Thompson prescribed medicines to help clear out Anne’s system by pushing the ‘matter most downward’ but this wasn’t successful and she kept being violently sick and in a lot of pain. Thompson treated her with an intensive regime of medications designed to clear her body and

Upon the sixth day after my first admission, coming to see her, I found her chearful, (the Pain of her Side and Feaver abated) with many hopeful signs of speedy recovery, onely she complained of a Weight of her left Side, tending downward toward the Kidneys, and a straitness of her Belly, but yet she thought a small matter more would perfectly cure her; so giving her precaution, I bad her go on to take what remained, charging her to give me notice if any thing fell out amiss.

A few days later, however, Anne’s friends called the doctor back as she was in terrible pain:

Now the first appearance of these was after a great Agony on Munday night, being the eleventh day; for the Sphincter of the Anus being notably dilated, a hard rough Body was discovered in the Fundament by a Midwife, or some of the officious Women there present, who by frequently assaying, and tender contrectation thereof, made shift to get out one of these deformed Stones (more friable then the other two) by fracture and piece-meal, and then forthwith sent to me to hasten to be a spectator of this monstrous Birth.

Despite the fact that these stones came out of her bottom, Thompson still likened them to a monstrous or deformed birth. The first stone was handed to him as he entered the house, and he looked on them with ‘just admiration’. The midwife and the assembled neighbours who had been tending Anne reported that what had come out so far was just a fraction of what remained inside and so Thompson

sent for a plain Barber Surgeon of the Town, Thomas Flemmin, since dead, whom I enjoyned to fetch me the strongest pair of Curling-Irons he had, which forthwith done, I directed him to insinuate and worm them in between the Sphincter and the Stone, to lay fast hold, and to try whether he could turn it about; which he did artificially, and setting a strong hand, pulled it out confidently in a trice. The other quickly followed, and the Patient was immediately freed from her dolorous condition, a large quantity of Urine issuing forth which had been stopped nigh forty eight hours.

Anne or ‘the miserable virgin’ as Thompson referred to her, made a full recovery and went on to marry and have children:

Ever since she hath enjoyed her health […] and since married an Innkeeper, Francis Chatterton, living now at Rumford at the Sign of the Dolphin, by whom she hath had two Children.

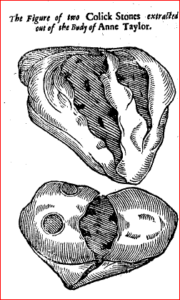

Thompson described the three stones in some detail, ‘Touching the first which the Midwife and some others brake out by their subtil working into it with their fingers […] , in my absence’ he said it seemed to be cylindrical in nature and as large as the later ones, but that he hadn’t seen it in detail, after his initial sighting, because the midwife had broken it up for people to keep as souvenirs. The last two he himself kept, the second of which was ‘Triangular, almost Equilateral, each side being about two inches three quarters in length, and near two in bredth’. Remarkably, Thompson ends his anecdote by announcing that anyone who was interested could come and see the two specimens in his house:

The Stones before spoken of are in the Authors keeping, at his Lodgings near to the Blue Boar Inne without Allgate; where any Ingenious Person that desires to be further satisfied concerning them, may be freely admitted to see them.

The book includes a drawing of the stones, presumably for those unable to visit his apartment in person.

Great story! And it interested me to see the midwife giving advice and assistance in a case which – despite the monstrous birth imagery – wasn’t about gynaecology or obstetrics. Nice praise of the midwife’s skills, too!

Yes, that struck me when I first read the story. I suppose that for a young woman with bad stomach ache the midwife was the first person everyone naturally thought to consult, presuming a gynaecological problem.