I have often mentioned that early modern men and women liked to exchange useful advice on medical treatments. We have seen that Samuel Hartlib sought out advice from his friends and that his friends were eager to help him find a remedy to prevent bladder stones. Manuscript recipe books are filled with notations that show where a remedy had come from and who else had tried it. The book attributed to Anne Brumwich for example included ‘a very good receipt for sore eyes commended by Mrs Worsley’, ‘a drink for an Ague w[hi]ch hath cured some that hath had it 2 years together’ and a sovereign powder to cure the stone, ‘approved by ye Lady Diby who could never find ease by noe meanes that docters could use & this hath freed her from all her terible fits’.1 Indeed it is likely that recipes became a form of social currency, something that could be given and exchanged and that created ties of friendship and bonds of reciprocity.

But it would seem that not everyone was always so happy to receive a flood of advice from every man and his dog.

In 1699 V. Ferguson wrote a letter to Hans Sloane outlining the sneaky manoeuvres he had used to avoid his friend’s advice. Apparently letting people believe his condition was serious (if not terminal) was preferable to hearing and trying to follow the medical advice of doctors, friends and family. Ignoring everyone, importantly, allowed him to follow what he thought was the best plan without adapting it to suit anyone else. The letter read as follows:

Sr I had the favor of your [letter on the] 31 [?] last post, and perceivd I omitted aquainting you I took vomits with utmost caution this being so Rationall and obvious a medicines

Im now to aquant you that all my friends both physicians in Dublin and here did so importune me to use many things were indeed Rationall, but many very diagreable to me on tryall, and my Relations did so press me to reiterated tryalls of those Recepts that was much against my pain I was overpressed with too much advise, and too many medicins and dayly declined till all men concluded me hopele ss; tho in truth I never thought myselfe past cure: when I had thus some respite from inportunings & looked upon as a gone man: having my bead still Rigtht and my judgment clear: I considered what bore (and what did not) with me, and layd down the best methode I could think on, both die-tetick and medicinall and had entred into it some few days ere I write to you resolving to lay aside all others and to live or dye by it: by which means God has allready so restored me that my stomach is almost at perfect ease and I mend to the wonder of all men, and by chrismas thinks to go ab[r]oard’2

ss; tho in truth I never thought myselfe past cure: when I had thus some respite from inportunings & looked upon as a gone man: having my bead still Rigtht and my judgment clear: I considered what bore (and what did not) with me, and layd down the best methode I could think on, both die-tetick and medicinall and had entred into it some few days ere I write to you resolving to lay aside all others and to live or dye by it: by which means God has allready so restored me that my stomach is almost at perfect ease and I mend to the wonder of all men, and by chrismas thinks to go ab[r]oard’2

V Ferguson.

The lucky outcome of this plan, according to Ferguson, was that his piles and the tumours in his stomach and anus had subsided enough to let him go on holiday for Christmas. Not everyone then was a willing or happy participant in the shared medical culture of early modern England, and not everyone was enthusiastic about trying numerous different remedies in order to satisfy the etiquette of helping friends and relatives in their time of need. It would be fascinating to see what Ferguson’s friends made of his ploy, here’s hoping there is another letter somewhere in the collection.

____________

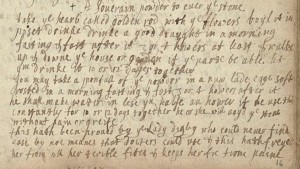

1. Wellcome Library, MS 160, pp. 7, 11, 27.

2. British Library, MS Sloane 4075, fol. 124.

© Copyright Jennifer Evans all rights reserved.

Those who are interested in receipes as social currency might like to have a look at Alisha Rankin, Panaceia’s Daughters: Noblewomen as Healers in Early Modern Germany (U of Chicago Press, 2013). She writes extensively about who gave recipes to whom, and what they hoped to gain.