A True English Bloodletting

by Dr Stephen Curtis

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Phlebotomy (or blood-letting) is perhaps the most infamous of all early-modern medical interventions. Synonymous with an outmoded view of the body and generally accompanied by lurid descriptions of bloodthirsty doctors cutting and cupping indiscriminately, the truth is actually that there was a whole wealth of knowledge and instructive material on how it should be carried out safely and correctly.

In particular, there were two vernacular treatises on phlebotomy published at the cusp of the seventeenth-century. The decision to publish such manuals in English was a strong signal of intent by the two authors, Nicholas Gyer and Simon Harward, as can be seen by their chosen titles. Gyer’s book, The English Phlebotomy: Or, Method and way of healing by letting of blood (London, 1592), refers to the language in which it was written, but also hints at a process of naturalisation for the medical technique itself. The later treatise, Harward’s Phlebotomy: Or, a Treatise of letting of Bloud (London, 1601), is even more striking in its title, with the author seemingly taking ownership of the very act of Phlebotomy. Both works, moreover, position themselves against perceived charlatans carrying out improper procedures and causing more harm than good to their unwitting patients. Gyer, addressing Sir Reginald Scot, famous anti-witchhunter and grower of hops, makes his targets clear:

These men [witchfinders], in mine opinion, should farre better please God, and much better deserve, of the Christian commonwealth, if they would speedily turne from this their heathenish Infidelity, extream folly, & barbarous cruelty, & seek rather by due execution of lawe & justice the blood of these bloodsuckers indeed, who for want of skil in this profitable practise of blood letting, in every corner of the country without controlment, either presently kyl, or at leastwise accelerate the immature deaths of dyvers faithful Christians to God, and good subjects to their Soveraigne.1

So what was bloodletting? Harward provides a clear definition:

Phlebotomy is the letting out of bloud by the opening of a vayne, for the preventing or curing of some griefe or infirmitie. I take in this place bloud, not as it is simple and pure of itself, but as it is mingled with other humours, to wit, fleame, choler, melancholy […] which all (as Fernelius sheweth) as they are contained together in the vaynes, are by one word usually called by the name of blood.2

Gyer highlights the skill required to let blood correctly, and in doing so outlines several of the diagnostic stages of the phlebotomist’s art: ‘I call it an artificiall incision, because it must not want art and judgement: For in it, consideration must be had of the inflicted wound: of the quantitie of the bloud: of choosing the aptest vaine: either to pull backe bloud, or to evacuate it quite: or to make it onely lesse in quantitie’.

This skill was not restricted to the dexterity required to carry out the incision itself though, as diagnosis involved both sight and, potentially, taste. The sample would be examined visually, with any imbalance being manifest, but there are also clear references to the tasting of blood as a way of judging its particular properties. Nicholas Gyer is squeamish about the use of such a diagnostic approach but is instructive about how one would interpret its results:

No man doth willingly tast detracted bloud, but if by chaunce it come into the mouth, and doo tast sweet, it is according to nature, good, and of perfect concoction. If it bee bitter in tast, it sheweth aboundance of choller: if it be sowre, sharpe, and restringent, it denotateth aboundance of melancoly: if unsavery, aboundance of flegme: if salt, the bloud is mixt with salt flegme.3

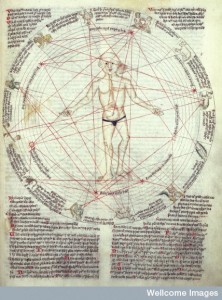

Phlebotomy was a complex business, both in its prescription and process. This complexity was exacerbated by the links between the body and the cosmos. Since phlebotomy was based so thoroughly on the cosmological aspects of humoralism the time and place of venesection were considered to be as important as the state and condition of the patient. The range of considerations can be seen in Gyer’s listing of the factors that would make phlebotomy particularly risky, merging as he does physical and environmental aspects:

Thou oughtest to beware of opening a veyne in a complexion too colde, in a Country too colde, in time of extreme paine in a member, after resolutive bathinges, after carnall copulation, in young age under fourteen, and in olde age, except thou have great confidence in the solidity of the Muscles, in the largenes and fulnes of the veynes, and rednes of the colour: such either young or olde, boldly may be let bloud.4

The influence of external effects on the appropriateness or efficacy of phlebotomy is perhaps best illustrated by Harward’s exhaustive commentary on the relationship between astrological sign and bloodletting:

The fittest time for letting bloud is when the signe (as we call it) or the moone is in Aries, Sagittarius, Cancer, Libra, Scorpio, Aquarius, or Pisces, unlesse in any of these signes the moone do predominate in that place that is to be let bloud, as in Aries the head, Taurus the neck, Gemini the shoulders and armes, Cancer the breast, stomack, and ribs, Leo the heart and back, Virgo the belly and bowels, Libra the raynes and loynes, Scorpio the secrets & bladder, Sagittarius the thigh, Capricornus the knees, Aquarius the legs, Pisces the feete.5

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Given the range of variables that had to be in alignment, it is remarkable that any actual bloodletting took place at all.

Phlebotomy could, of course, be a risky remedy. The potential for bloodletting to be taken to extremes was always present, hence the necessity for careful diagnosis and prescription. The loss of a patient was an occupational hazard however. Gyer’s warning against the effect this could have on a surgeon’s reputation concluded that it was better to leave the illness than risk losing the patient:

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

That practitioner which setteth by his credite, and will avoide ill speeches, must never through bleeding, bring his Patient to Syncope: because the same being, as it were, an image of death, terrifieth the standers by, and putteth the Patient in a great hazarde of his lyfe. Yea, and it is better to let the patient still remaine in griefe, than to take away with the disease, life it selfe.6

The focus here does appear to be the practitioner’s good name, however, with the wellbeing of the patient secondary to the potential for ‘ill speeches’.

Phlebotomy by itself was not a guaranteed panacea for the early modern ailments for which it was prescribed. It was only effective when combined with, and followed by, the kind of controlled intake discussed within the popular dietary regimens. Without such moderation, the bloodletting was in vain, hence Gyer’s warning that ‘there is such force in moderat diet, to eschew sicknes, that without observation thereof, Phlebotomy is to no purpose.’7 Bloodletting, therefore, was a medical practice of last resort, but one that has dominated the popular memories of early modern medicine for centuries.

Dr Stephen Curtis currently teaches at Lancaster University, where he carried out his PhD research entitled ‘An Anatomy of the Tragedy of Blood’. He specialises in early modern drama and the body. Although his research comes from a literary background, his head has been turned by the delights of the medical humanities. He is currently working on writing his thesis into a monograph, as well as carrying out research on other early modern bleeding and indulging in a fascination with chameleons in the period. He tweets from @earlymoderndude.

Dr Stephen Curtis currently teaches at Lancaster University, where he carried out his PhD research entitled ‘An Anatomy of the Tragedy of Blood’. He specialises in early modern drama and the body. Although his research comes from a literary background, his head has been turned by the delights of the medical humanities. He is currently working on writing his thesis into a monograph, as well as carrying out research on other early modern bleeding and indulging in a fascination with chameleons in the period. He tweets from @earlymoderndude.

_____________________

1 Harward, p.1.

2 Gyer, p.25.

3 Gyer, p.257.

4 Gyer, p.73.

5 Harward, pp.92-3.

6 Gyer, pp.148-9.

7 Gyer, p.263.

I’m assuming that the working classes would be saved of this practise by cost. Some plebs useds as guinea-pigs. I imagine a lot of fainting through depleted nutrition?