Today a whole range of sleep disorders are recognised by medical science; a brief glance at the NHS direct website shows a list including: insomnia, sleep apnoea, and sleep paralysis. It is likely that we have all felt the effects, to whatever degree, of disrupted sleep and recognise that if experienced regularly disrupted sleep can have a severe impact on our health. Our early modern forebears were similarly concerned about the impact sleep could have on their health and well-being.

Today a whole range of sleep disorders are recognised by medical science; a brief glance at the NHS direct website shows a list including: insomnia, sleep apnoea, and sleep paralysis. It is likely that we have all felt the effects, to whatever degree, of disrupted sleep and recognise that if experienced regularly disrupted sleep can have a severe impact on our health. Our early modern forebears were similarly concerned about the impact sleep could have on their health and well-being.

According to early modern medical doctrine the body could be kept in a state of health by regulating the six ‘non-naturals’: air, food and drink, sleep and waking, movement and rest, retention and evacuation (including sexual activity) and the passions of the soul (emotions).1 So early modern men and women, like us, acknowledged the importance of getting enough sleep and of not sleeping to much. Samuel Pepys noted in his diary when his sleep had been disturbed and shows us that then, as now, sleep could be disrupted by everyday and mundane things: Sunday 15th January 1659/60 ‘Having been exceedingly disturbed in the night with the barking of a dog of one of our neighbours that I could not sleep for an hour or two, I slept late, and then in the morning took physic, and so staid within all day.’

In addition the role sleep had in the non-naturals, sleep was also connected to the humoral temperament of the body. As regular readers will now be aware, the body was thought to be made up of a balance of the four humours; blood, yellow bile (choller), black bile (melancholy) and phlegm. The particular levels of these humours in each individual’s body resulted in their unique constitution. Each of these constitutions was thought to be pre-disposed to certain amounts of sleep and certain types of dreams. John Fage wrote of ‘flegmaticke’ men in The Sicke-Mens Glasse (1606) that they were ‘very dull, heavy, slouthfull sleepy, forgetful, cowardish, fearefull, covetous, self-lovers, slow of motion, shamfast & sober.’2 Following on from this Fage noted what each constitution would dream of, in many cases these reflected the elemental nature of the humour that dominated the body. So hot and dry choleric men were thought to ‘dreame of fire, fighting and anger, of lightening & dreadfull [burning] of ayre’.3 While sanguine-phlegmatic men would dream ‘of flying in the aire, and falling downe from some mountaine or high place into water or such like.’ 4 Fage included this information so that men, and women, would be able to identify their own constitution and order their regimen sufficiently to maintain health; dreams were thus one way in which men and women could attempt to know and understand their own bodies.

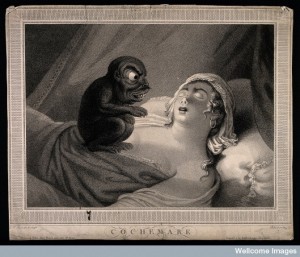

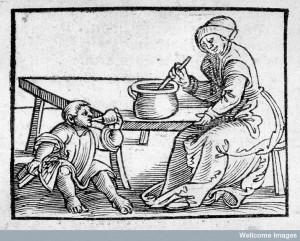

Dreaming and disturbed sleep were more than just signs of the constitution though. ‘Nightmares’ were accepted in medical treatises as a specific medical condition. The disorder referred to in these treatises as ‘Night-mare’ (although I am against retro-diagnosing) is remarkably similar to modern day sleep paralysis. According to the NHS direct website this is ‘a temporary inability to move or speak that happens when you are waking up or, less commonly, falling asleep’ that although harmless can be ‘very frightening’.5 Early modern descriptions of this disease were in some ways just the same as this. Philip Barrough in The Method of Physick explained that patients in this state felt themselves oppressed by a great weight in the night, and were unable to speak.6 This disease he revealed was caused by ‘excesse of drinking, and continuall rawnes of the stomake, from whence do ascend vapours grosse and cold, filling the ventricles of the brain, letting the faculties of the braine to be dispersed by the senewes.’ 7 Once these vapours were removed the disease would be cured.

Dreaming and disturbed sleep were more than just signs of the constitution though. ‘Nightmares’ were accepted in medical treatises as a specific medical condition. The disorder referred to in these treatises as ‘Night-mare’ (although I am against retro-diagnosing) is remarkably similar to modern day sleep paralysis. According to the NHS direct website this is ‘a temporary inability to move or speak that happens when you are waking up or, less commonly, falling asleep’ that although harmless can be ‘very frightening’.5 Early modern descriptions of this disease were in some ways just the same as this. Philip Barrough in The Method of Physick explained that patients in this state felt themselves oppressed by a great weight in the night, and were unable to speak.6 This disease he revealed was caused by ‘excesse of drinking, and continuall rawnes of the stomake, from whence do ascend vapours grosse and cold, filling the ventricles of the brain, letting the faculties of the braine to be dispersed by the senewes.’ 7 Once these vapours were removed the disease would be cured.

In these descriptions nightmares appear rather innocuous, but as several medical treatises show the descriptions could be more sinister. Robert Johnson’s description of the disease started as Barrough’s did noting that the patient felt oppressed by a weight and could not move or speak.8 But he continued to described in more detail how ‘When the fit is upon the sick, they do imagine that some Witch or Hag lieth hard on their Breast or Stomach, (from whence it hath also acquired that Name) in which they cannot stir, nor call for help, though they have a great desire, and do strive very much to cry out, but are possessed with a panick fear.’9 It was from this particular symptom, he noted, that the disease acquired its Latin name ‘Incubus’ (meaning an evil spirit or demon).10 Other texts also called this the Night-hag. In these descriptions the disease was not only characterised by a sense of helplessness but by the sensation of being maliciously threatened by a diabolical being.

In these descriptions nightmares appear rather innocuous, but as several medical treatises show the descriptions could be more sinister. Robert Johnson’s description of the disease started as Barrough’s did noting that the patient felt oppressed by a weight and could not move or speak.8 But he continued to described in more detail how ‘When the fit is upon the sick, they do imagine that some Witch or Hag lieth hard on their Breast or Stomach, (from whence it hath also acquired that Name) in which they cannot stir, nor call for help, though they have a great desire, and do strive very much to cry out, but are possessed with a panick fear.’9 It was from this particular symptom, he noted, that the disease acquired its Latin name ‘Incubus’ (meaning an evil spirit or demon).10 Other texts also called this the Night-hag. In these descriptions the disease was not only characterised by a sense of helplessness but by the sensation of being maliciously threatened by a diabolical being.

This terminology and understanding was not new to the early modern period, but does shed some light on the phrase ‘nightmare’ and show that originally this was a form of what we would perhaps call night paralysis involving vivid dreams of being strangled or oppressed by a witch or hag. It also shows us that for early modern men and women there was more to the stuff of dreams than mere imagination.

__________________________________________

1. Andrew Wear, Knowledge and Practice in English Medicine 1550-1680 (Cambridge, 2000) p.156.

2. John Fage, Speculum Ægrotorum. The Sicke-Mens Glasse: Or A Plaine Introduction whereby one may give a true, and infallible iudgement of the life or death of a sick bodie … (London, 1606), Sig. Ir

3. Ibid, Sig. H3r.

4. Ibid, Sig.Ir.

5. http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/sleep-paralysis/pages/introduction.aspx

6. Philip Barrough, The Method of Phisicke … (London, 1583), p.34.

7. Ibid.

8. Robert Johnson, Praxis Medicinae Reformata: Or, The Practice of Physick Reformed … (London, 1700), p. 35.

9. Ibid, p.36.

10. Ibid, p. 35.

© Copyright Jennifer Evans, all rights reserved.

I hesitate to think of witchcraft accusations and dreams in such terms, because of the danger of anachronism and retrospective diagnosis. However, I have found it useful to remember that hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations can readily seem very real, that they are not at all uncommon, and that the content of the hallucinations will be culturally specific, as will the interpretation, though I have problems with a full-blown culture-bound disease explication.

The night spectre of the accused witch is to be found widely in witchcraft cases, as corroborating evidence. I’ve seen it in the Yorkshire cases and it turns up at Salem. It can’t form the central accusation, unless the claimed harm was associated with such a visitation. In the European cases and debates, there was discussion about how the witch could be demonstrably at home in bed while seen elsewhere by a witness, inside a locked house, and the notion of a disembodied spectre was the response of the pro-prosecution side of the debate. For historians, this issue famously arose in the trials of the benandanti of Friuli, though those cases did not enter into contemporary debate. Disembodiment posed its own set of problems for early modern intellectuals, as it did with the physical acts attributed to demons and angels.

Beliefs about being ridden by the night hag, in which the sense of physical oppression has been “explained away” by the hallucinations, are prominent in the West of England during the early modern period and through into the 20th century in Newfoundland.

Thank you David, this is all really interesting.