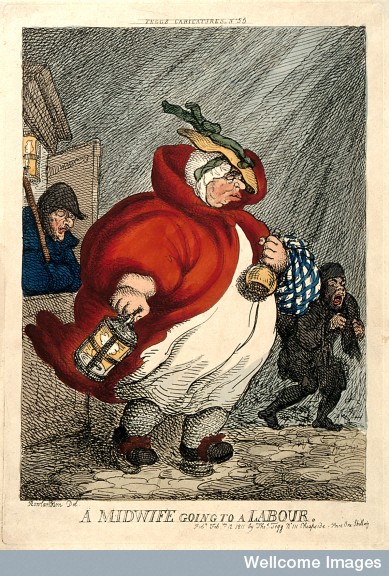

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

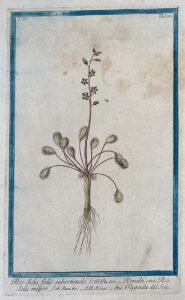

Midwives have been mentioned often on this blog. They were a central feature of many women’s birthing experiences in the early modern period. Their work, character and bodily condition have, at various points, all come under the scrutiny of their contemporaries and, later, historians. Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries some male commentators – physicians, man-midwives and others – complained that midwives were ignorant and unskilled practitioners who endangered the lives of women and their unborn babies. This was sometimes presented as a diatribe against all midwives or as subtle comments inserted into medical discussions of obstetrics. For example, John Hall’s Select Observations of English Bodies noted that the retention of the afterbirth (placenta) ‘happens very often through the unskilfulness of the Midwife, but always with great danger of the Mother.’1 Criticising others was one way to establish your own credentials and so criticisms also appeared in texts attributed to midwives themselves. Jane Sharp wrote disparagingly about the skills of some midwives: ‘I Have often sate down sad in the Consideration of the many Miseries Women endure in the Hands of unskilful Midwives; many professing the Art (without any skill in Anatomy, which is the Principal part effectually necessary for a Midwife) meerly for Lucres sake.‘2 These views were, of course, not universally held, or even consistently held, and many male medical practitioners and writers revealed that they valued the knowledge of midwives. For example, George Bate who recorded in his treatise a remedy for barrenness recommended by a midwife: ‘One Secret communicated to me by an ancient Midwife I think fit to disclose, viz. that it makes barren Women fruitful; and that she had given it to some Scores upon the account, and with the desired success’.3 Not only did he think this advice was good enough to repeat but he was sure to mention that the remedy was effective.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Women were for much of the period excluded from university education, and so had no access to the type of knowledge that some male writers suggested was necessary for medical practice. In response midwives sometimes argued that medical practitioners had no physical experience of the female body and so could not understand childbirth in the way that they did. They could feel and touch the female body and many had given birth themselves providing them with a form of experiential knowledge physicians could never hope to acquire. Many also learnt their trade through an apprenticeship and spent years accompanying an experienced midwife before striking out and going it alone.4

The potentially dangerous nature of a midwife was not only described in medical treatises and discussions between midwives and their rivals though. It also appeared in the popular ephemera of the seventeenth such as the ballad, The Mistaken Mid-wife. This song sheet dated by the Bodleian as being published in London between 1674 and 1678 presented the tale of an unfortunate midwife who fell into a life of deceit and crime.5 As mentioned above many midwives were themselves women who had born many children. In the Mistaken Midwife though the protagonist is denied this knowledge and has to live with the stigma of being barren:

‘A Midwife lately in this town,

by folly was misled,

Who many a woman had lain down,

and brought them unto Bed;

She to three husbands married was,

which made her almost wild,

Because in all that time~ alas,

she could not have a Child’

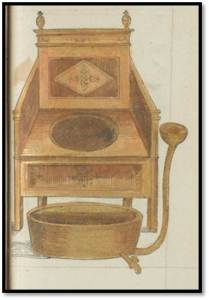

Having thus failed to conceive a child with her third husband and becoming desperate ‘to take off the scandal of Barreness’ she hatched a plan to deceive those around her and claim that she had conceived and carried to term a child of her own. The midwife’s plan moved from deceitful to sinister as the supposed pregnancy progressed:

‘A little Pillow she prepar’d.

which cunningly she plac’t,

And to the women then declar’d,

she should not be disgrac’t;

Quoth she my time of joy is come,

I now am big with child,

I feel the babe spring in my womb·

and thus she them beguil’d.

…

HEr simple Husband he poor man,

knew nothing of the Cheat,

But to provide what e’r he can,

of dainties for her Meat:

For fear she should her longing lose,

and what she went withal;

Thus did she lead him by the Nose,

and made him pay for all.

And now the time it did draw nigh,

she should be brought to bed,

Great preparations spèedily,

was ready furnished:

And all things put in order d![]() e,

e,

against the joyful hour;

With child-bed linnen fine and new,

according to her power.

And so this Wretch provided had,

to compass her own ends,

A child which had been buried,

and sent for none but friends:

Who privy were unto the Plot,

pretending suddain pains,

That she delivered was God wot,

but now the rest remains.

The midwife used the remains of a dead child and claimed it was her own. The ballad concluded with, as we would expect, the woman receiving her comeuppance – several women, who were suspicious all along, reported her crime and she was questioned by a jury of matrons (a groups of wise women called upon by the courts) about her so called pregnancy and discovered the truth of her actions. The midwife was sent to prison, where, according to the ballad, ‘she doth abide’ still.

This song focused on several issues central to early modern discussions of fertility, pregnancy and the practices of midwives: the ignominy of infertility, the ability of the female body and women to deceive those around them – particularly men, and the pain of childbirth. The final line of the ballad lingered on this particular point noting that

‘Thus did she strive for to obtain,

what nature did deny,

To blind the world it was in vain,

her fraud they did espy:

How’re it was a cunning slight,

as ever did befall:

To bring a Child into the World,

and feel no pain at all.’

Not only was this woman detestable because she had used her access to the stillborn children of others for her own ends, corrupting and tainting the practice of midwifery, but she had tried to claim motherhood without experiencing the physical changes and pain it entailed. To see the ballad in full please go to the fantastic Broadside Ballads Online site, by the Bodleian Library, Oxford. To read about the real case behind this musical retelling please visit Sarah Fox’s post at the Perceptions of Pregnancy Blog.

Broadside Ballads Online from the Bodleian Library Oxford.

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

_____

1. John Hall, Select observations on English bodies of eminent persons in desperate diseases first written in Latin by Mr. John Hall (London, 1679), pp. 197-8.

2. Jane Sharp, The Midwives Book (London, 1671), preface.

3. George Bate, Pharmacopoeia Bateana, or, Bate’s dispensatory translated from the second edition of the Latin copy, published by Mr. James Shipton (London, 1694), p.543

4. There is a wealth of scholarly literature on the training and learning of midwives and the encroachment of the man-midwife into the birthing room. It outlines the complex nature of these discussions better than I ever could in one blog post.

5. Anonymous, The Mistaken Mid-wife (London, 1674-1678).

3 thoughts on “The Mistaken Midwife”

Comments are closed.