I have recently been working on the physical recovery of early modern women who suffered a miscarriage. This has taken me back to reading midwifery case notes and letters describing women’s experiences in birth. What has struck me again, as it does on every reading, is the extreme physical trauma some early modern women experienced as part of their birthing stories.

Reading Thomas Chamberlayne’s 1656 publication, The Compleat Midwifes Practice that shared the knowledge and case notes of Louise Bourgeois, a French Royal midwife, there are numerous cases of women experiencing physical problems related to birth. One of these cases reveals that the problems women faced were not always the result of the birth process itself, but complications created by past physical trauma and in particular by domestic violence. More information on early modern domestic violence can be found in Joanne Begiato’s work.

Jennine Hurl-Eamon has shown in her work that women prosecuted men in the Westminster courts whose violence and physical assaults caused them to suffer a miscarriage. She has shown that women did this to reinforce notions of patriarchy that expected men to protect pregnant women. They emphasised their own loss and trauma to show how ‘good men’ should behave. It is not clear whether Thomas Chamberlayne or Louise Bourgeois intended to do the same thing with their publications, but it is clear that readers were shown the dangerous consequences of men’s violence.

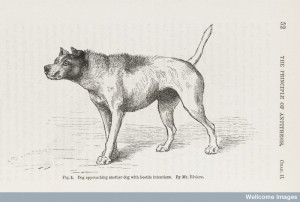

The text includes one case of a young woman whose ‘ill Husband’ had ‘given her a blow upon the belly with his foot, and had broken the Peritoneum‘ (the lining of the cavity supports many of the abdominal organs). The consequence of this injury was that the womans ‘guts hung down’ inside the body. Whenever she was pregnant her womb prolapsed or ‘jutted out’ so that the ‘Infant had not liberty to turn it self’ for birth. The midwife afraid of losing the woman had called in a surgeon for the previous two births. Louise exclaimed that he had ‘already killed two of her children’.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

images@wellcome.ac.uk

To remedy the situation Louise recommended that the woman use an adapted swathing band. These were lengths of fabric used by pregnant women to help support their expanding bellies. An example can be seen in this image of a woman who supposedly gave birth to twenty children. In the case of the young woman Louise was treating the band had to be adapted and worn like a hernia truss:

I caused her to wear it as they that are burst do wear, half slopps, lying smooth with cushions within, and never to rise without this whether bigg [pregnant] or no; which she did, and stil does, and bears as fine children, and lies in as wel as any other woman.

This simple accessory counteracted the injuries from the initial attack and, apparently, allowed the woman to carry and give birth to live children, giving the story a happy conclusion. This was a conclusion, of course, that emphasised that Louise’s skills were superior to the other midwife and the other surgeon involved.

The story though, beneath the surface, is about more than a midwife’s skill. It served as a reminder to readers at the time that violent actions could have serious consequences for childbearing women and that pregnancy was something to be protected. Moreover, it serves as a reminder to modern readers of the significant physical difficulties child bearing women faced in the seventeenth century.

Help and support for those experiencing domestic violence can be found here: Women’s Aid and Refuge.