Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

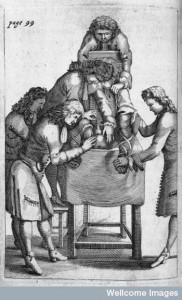

You may remember that some time ago I wrote a blog post about ‘the Stone’ (kidney stones or bladder stones). I looked at how remedies for the stone were described and discovered. The post also emphasised how painful this disease could be and how dangerous its cure was. Surgical operations to remove stones from the bladder, or to remove stones that had become lodged in the urethra or penis, could result in permanent damage or death. If you remember Samuel Pepys, the famous diarist, celebrated the anniversary of his survival of lithotomy (cutting for the stone).

Recently I have been working through the papers of Samuel Hartlib, available through a wonderful database created by the University of Sheffield. Samuel was a man of science who lived between approximately 1600 and 1662. He was part of an extensive circle of letter writers and was known for disseminating knowledge and books. He is associated with the publication of at least 65 pamphlets, on a range of topics including religion and chemistry. In 1642 though he began to suffer from the stone, and by 1656 his condition had confined him to his house.1

Many of his correspondents wrote to him about his troubles and he sought their help in finding treatments that would alleviate his pain and discomfort. It is not always clear whether his stones were lodged in the kidney or the bladder; in one letter Lady Ranalagh stated that she had found a French surgeon in Dublin who possessed a good remedy, which he would be happy to provide if Hartlib could confirm that his stones were in his kidneys.2 In a later letter, dated 1661, another friend though sent him a remedy specifically for stones in the bladder.3 It may be that Samuel was unable to identify the exact nature of his problem, or, as medical writers suggested could happen, his stones moved from the kidneys to the bladder. Either way it is apparent that he was keen to find relief from this problem and to avoid the surgeon’s scalpel. Those he spoke to sympathised with him and frequently recorded their hopes for his recovery, or temporary respite: Robert Wood, for example, noted that he ‘should much rejoice if God would to give you ease from your tormenting paines.’4

In his notes Samuel recorded numerous potential remedies. Of one he wrote, ‘A knight in Cheshire with many others have found a wonderful deale of good in the stone by using the powder once a weeke of dryed Haw’s drunke in white wine’. He also recorded at least two remedies made from goats blood.5

In his notes Samuel recorded numerous potential remedies. Of one he wrote, ‘A knight in Cheshire with many others have found a wonderful deale of good in the stone by using the powder once a weeke of dryed Haw’s drunke in white wine’. He also recorded at least two remedies made from goats blood.5

He also described medicines made from radish roots, the subject of my previous post: ‘Take 4, or 5. morning to gether fasting an ounce of sirripe of Radish, and after that to a little wine glase of ale putt to halfe an ounce of the said sirrip, drinking it a weeke toether or longer as you find ease’.6

Hartlib’s papers also suggest that he was very interested in the side effects of his disorder, it is likely he was suffering from a range of associated symptoms from which he also sought relief. One undated piece of paper records ‘Mr Boyles excellent Receipt against Ulcer in the bladder’, which was three ounces of the clarified juice of ribwort taken every morning.7

Just as troubling as ulcers in the bladder, a letter from Anthony Metcalfe described in detail that Hartlib was finding blood in his urine, although the letter also made it clear that this hadn’t caused any additional pain. Metcalfe showed great eagerness to offer his own lengthy advice on this matter. He wrote

‘I am sorry to heare of the infirmitie which hath lately seised on you … The infirmitie you complaine of, is a bloody urine in the beginning of this mallady, but now it is growen to be of a browenish but I feare of a blackish colour, made without paine onely a pricking and gripeing both in your back and bladder which you complained of longe before any blood appeared in your urine.’8

Hartlib was not though just the recipient of information about the stone, but was evidently looked to as source of information based on experience and great knowledge. Robert Wood wrote to Samuel in 1661 saying ‘I should be very glad to heare of any good effect upon your selfe of the Medicine you expected from Amsterdam & where of you sent me some account from Mr Dury in November last, which I having imparted to my Landlord Mr Bonnell a great Travellor & who is frequently troubled with the like distemper of the Stone as you, would be very glad if he heares that the Medicine succeed upon you’.9

Samuel’s stone-induced suffering was a key theme within the letters and notes of his circle of correspondence. Together they formed a network of medical enquiry and communication, that included men and women, sufferers and healers, all seeking tirelessly a remedy that would bring relief for a painful problem and its associated symptoms.

____________

1. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, www.oxforddnb.com, s.v. ‘Samuel Hartlib’, accessed 21.03.14.

2. Recipes for the stone, Hartlib & Scribe A, 14-20 February 1657, [60/4/13a -13b], Greengrass, M., Leslie, M. and Hannon, M. (2013). The Hartlib Papers. Published by HRI Online Publications, Sheffield [ available at:http://www.hrionline.ac.uk/hartlib ].

3. Letter, John Dury to Hartlib, 15 October 1661 [4/4/38A], Greengrass, M., Leslie, M. and Hannon, M. (2013). The Hartlib Papers. Published by HRI Online Publications, Sheffield [ available at:http://www.hrionline.ac.uk/hartlib ].

4.Letter, Robert Wood to Hartlib, 1 January 1661, [33/1/77A], Greengrass, M., Leslie, M. and Hannon, M. (2013). The Hartlib Papers. Published by HRI Online Publications, Sheffield [ available at:http://www.hrionline.ac.uk/hartlib ].

5. Ephemerides 1651 Part 2, Hartlib, [28/2/17A] and [29/7/3B], Greengrass, M., Leslie, M. and Hannon, M. (2013). The Hartlib Papers. Published by HRI Online Publications, Sheffield [ available at:http://www.hrionline.ac.uk/hartlib ].

6. Recipes for the stone, scribal hand & Hartlib [60/4/209a], Greengrass, M., Leslie, M. and Hannon, M. (2013). The Hartlib Papers. Published by HRI Online Publications, Sheffield [ available at:http://www.hrionline.ac.uk/hartlib ].

7. Boyle’s Recipe for Ulcer in the Bladder, [60/4/212A], Greengrass, M., Leslie, M. and Hannon, M. (2013). The Hartlib Papers. Published by HRI Online Publications, Sheffield [ available at:http://www.hrionline.ac.uk/hartlib ].

8. Letter, Anthony Metcalfe to Hartlib, undated [30.2.13a], Greengrass, M., Leslie, M. and Hannon, M. (2013). The Hartlib Papers. Published by HRI Online Publications, Sheffield [ available at:http://www.hrionline.ac.uk/hartlib ].

9. Letter, Robert Wood to Hartlib, 1 January 1661, [33/1/77A], Greengrass, M., Leslie, M. and Hannon, M. (2013). The Hartlib Papers. Published by HRI Online Publications, Sheffield [ available at:http://www.hrionline.ac.uk/hartlib ].

Good to see. Such material helps us to see the complexity of hierarchies of resort, the role of diagnostic and therapeutic differences within such hierarchies, and the relationship between professional care and communicated domestic remedies.

All too few sources are sufficiently detailed or comprehensive to allow us much insight. Of course, it’s a pity that Hartlib is so very unrepresentative but he’s only an extreme example of how lots of people dealt with painful of inconvenient chronic ailments that were curable, but only with risk or difficulty.