Lichfield Garrick Theatre and Studio, Saturday 15 March 2014

Reviewed by Sara Read

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

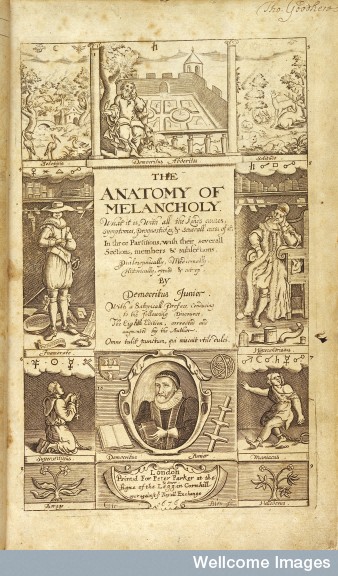

The decision to construct a stage performance from Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621) is certainly an innovative one. The wordy nature of the book, which started out at over 300, 000 words in 1621 and ended up at over half a million words by the time of the posthumous 1651 edition, isn’t one which immediately lends itself to such a task. The book aimed to bring together all the diverse writings on the topic of melancholy, a disease which closely identifies with our current diagnosis of depression, into one volume. The programme acknowledged the difficult task before the audience to concentrate on the readings in its invitation to them to tune in and out of the often long and dense content and let their mind wander before focussing in again.

Performed in a series of sections (see illustration below) using visual aids such as flipcharts to map the progress for the audience, the actors demonstrated phenomenal feats of memory. The care in planning and production showed too as the actor’s held up flash cards in place of the marginal notes which gloss which classical author the argument is being taken from. This method was employed too to offer translations of the Latin phrases with which Burton’s prose is interspersed. It was a surprise to see the reliance on paper props, and one wonders why modern technology wasn’t such a large screen wasn’t employed instead. However, the numerous pieces of paper and turning of the pages on the many flipcharts does serve as a nod to the number of pieces of paper, and the complicated ordering of pages and sections which must have taken place in the construction and printing of the original work.

Performed by a cast of four: Rochi Rampal, Gerard Bell, Craig Stephens, and Graeme Rose, the readings were broken up with occasional songs and dances, such as at the suggestion that drinking German beer might serve as a cure – in moderate quantity. The discussion of the problems with universities handing out worthless degrees to poor scholars based on minimal learning raised a laugh in the audience, showing that the problems with the ‘youth of the day’ are as old as time.

Image credit: http://www.stanscafe.co.uk/

Ultimately the show was more of a dramatic reading than a stage show as such. The appeal of this for a non-specialist audience is debatable. For anyone with an interest in seventeenth-century medicine and culture, however, the opportunity to listen to an extended reading of a seventeenth-century non-dramatic prose text is a rare treat. It serves to re-familiarise yourself with a text and draw out new aspects even if you know the text well.

The production attracted support from the Wellcome Trust, the Arts Council, and the Warwick Arts Centre. It is great to see innovative and experimental productions dealing with medical history such as this receiving this support.

_______

© Copyright Sara Read all rights reserved