In a previous post I wrote about the ways in which early modern medical texts discussed miscarriage and the remedies they suggested in order to prevent this from happening. But as I hinted at, one of the issues with miscarriage was that, potentially, once it had been identified it was too late to prevent it from occurring. In this post I want to consider miscarriage a little more and think about what happened when this sad and incommodious event happened.

To do this I am going to discuss a letter housed in the Somerset Heritage Centre, written by Bernard Smith addressed to Edward Clarke, about his wife Mary’s miscarriage.1 The letter read as follows,

Sir

Monday last I gave you an account how I found your Lady, and accordingly as I wrote it happened, for before midnight she had miscarried, after which she did always vomit all she did take ; and had a great paine at her stomack. Soo I gave her powders to sweeten the humours together with pearle cordials which did much abate the vomiting, but the paine is not which is the only thing she complains of. The last night Dr Musgrove came by the orders of some friend or other, whom I know not who hath directed some more of the powders and Cordialls to Sweeten the aforesaid humours in her stomack, which I hope will all doe well, which is all I can say at present only this ther was no [child] but a false conception which much of [noisily] came off. S[i]r I for no reason but all will be well which is the hearty desires of

Sr your most humble servant Ber: Smith

Madam …. sends her service to you and desires your pardon for not writing.

[1695} Chiply Saturday sept 14.95

This letter is fascinating for several reasons. Firstly it is a letter about a rather intimate and personal female health issue between two men. Much of the scholarship on reproductive medicine focuses on the ways in which these issues were the province of women. Yet here we can see that this was not simply an issue for the woman herself (or an all female group of midwives and female friends). Bernard Smith was an apothecary in Taunton, and eventually became mayor.2 As an apothecary Bernard was perhaps not the type of practitioner we would expect to find assisting in this particular instance – he was not a midwife, man-midwife or surgeon. Yet here he confidently asserted his own medical knowledge and experience to Edward, and assured him that he did indeed know best. He described the medicine he used and the miscarriage itself in detail, perhaps suggesting that he expected Edward to understand the physiology of miscarriage and the medical responses required.

Secondly, this letter touches upon an issue that is usually considered in relation to illegitimate births and single women. In her seminal article on ‘Secret Births and Infanticide’ Laura Gowing explains how some single women faced with possible legal ramifications for still birth or infanticide attempted to deny their pregnancies by affirming that although something had happened to their bodies what had passed from them was not a child.3 Gowing cites the example of Anne Peace who claimed that she had crouched down to urinate ‘And then and there did pass from her body a thing like a gristle.’4 It would appear from this letter, however, that it was not only single women that sought to deny the eventual viability of a lost pregnancy. In this case a married woman, who had every right to be pregnant, is described as having not miscarried a viable foetus but a false conception. False conceptions were described in most medical texts that dealt with generation as masses of one form or another. Jane Sharp’s The Midwives Book described false conceptions (also known as mola/moles) as,

‘The true Mole is a mishapen piece of flesh without figure or order, it is full of Veins and Vessels with discoloured veins or membranes of almost all colours, without any entrails or bones, or motion; it is bred in the wombs hollowness, and cleaves fast to the sides of it but takes no substance from it, sometimes it hath a skin to cover it and is empty within, sometimes it is long or round.5

It is not entirely clear what the motivation for describing the miscarriage in these terms is. We can perhaps speculate that using this language may have diminished the sense of loss felt by the mother and father; they had in fact not lost a potential child and heir, only an un-formed mass of no value. This may also have served to transform this event from a ‘sad and incommodious’ happening into more normal instance of ill-health.

This brings me to the final way in which this letter is fascinating (or maybe it is only fascinating to me), which is how this medical problem was dealt with. It would appear from the letter that Smith was most concerned about the pain and vomiting Mary Clarke was experiencing and used his own recipe of ‘pearle cordial’ in order to ease these symptoms and restore her health. Nicholas Culpeper’s translation of the Royal College of Physicians Dispensatory described pearls as ‘wonderful strengthener to the heart, encrease milk in nurses and amend it being naught, they restore such as are in consumptions, both they and red Correl preserve the body in health an resist fevears.’6 Thus it would appear that Smith picked a medicine that would have been considered useful in this situation strengthening the patient and preventing consumption and fever. In Smith’s opinion this was successful in abating the vomiting, although it did not lessen the pain Mary was in. However, he complains that other friends who he didn’t know called for the assistance of a doctor, perhaps they were not so eager to believe in the efficacy of the pearl cordial and powders. Yet this only serves to emphasise that Mary was closely attended by an apothecary,, several friends and a physician, who each tried to help her recover.

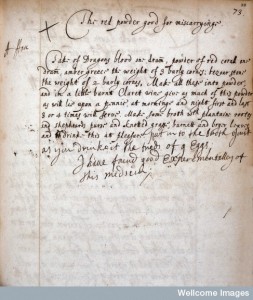

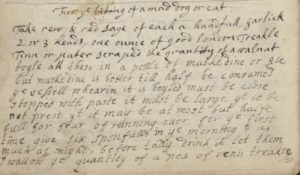

The treatment Smith chose does not bear much resemblance to those suggested in manuscript recipe collections. It is rare to find recipes explicitly described as being for women who had suffered a miscarriage, as opposed to those who were likely to suffer a miscarriage but some examples do exist. It would seem that in most of these cases the authors worried about haemorrhaging after a miscarriage: both Elizabeth Okeover’s book and an anonymous seventeenth-century book included a remedy for this:

The treatment Smith chose does not bear much resemblance to those suggested in manuscript recipe collections. It is rare to find recipes explicitly described as being for women who had suffered a miscarriage, as opposed to those who were likely to suffer a miscarriage but some examples do exist. It would seem that in most of these cases the authors worried about haemorrhaging after a miscarriage: both Elizabeth Okeover’s book and an anonymous seventeenth-century book included a remedy for this:

First take pigge dunge not, and apply it hot in a cloath to the part, then take a spoonefull of her owne M.P. that flowes, and give it her to drinke in a little posit drinke or Aleberry it will turne the course of the blood by occationing vomitting or wretchinge.7

The anonymous collection also contained a ‘drinke prescribed my Sister in her violent Flux after her Miscarriage.’ This was a long regimen that included drinking plantane water and red rose water and eating dates roasted in red wine, amongst other things.8 Nowhere in this regimen was there any mention of pearl. Interestingly the first of these remedies was also intended to cause vomiting in order to stay bleeding and so was clearly designed for a different purpose to Smith’s cordial. As with all other areas of medical treatment in this era then it would seem that recipes were adapted to suit particular circumstances and were designed to do different things based on the needs of a specific patient.

Although pig dung and menstrual blood might not be the most appealing of medicines it is clear from this letter and the evidence of other medical texts that in the unfortunate event that a woman did miscarry friends, doctors and spouses were anxious to restore the mother to health and prevent her own death or lingering illness. In particular they strived to ease pain, vomiting and haemorrhaging.

_____________________________

1. Taunton, Somerset Heritage Centre, DD/SF/2/42/11, File of deeds includes letter to Edward Clarke from Ber. Smith about Mary Clarke’s miscarriage and subsequent illness

2. I am grateful to Professor Jonathan Barry for helping me identify Ber: Smith.

3.Laura Gowing, ‘Secret Births and Infanticide in Seventeenth-Century England’, in Past & Present, Vol. 156, 87-115.

4 Ibid, p. 98.

5. Jane Sharp, The Midwives Book … (London, 1671), p.106.

6. Nicholas Culpeper, A Physicall Directory, or, A Translation of the London Dispensatory made by the Colledge of Physicians in London … (London, 1649), p.73.

7. London, Wellcome Library, MS 7391, English Recipe Book, 17th Century, p.126; London Wellcome Library, MS 3712, Elizabeth Okeover, p.192.

8. Ibid, pp.141-2.

© Copyright Jennifer Evans, all rights reserved.

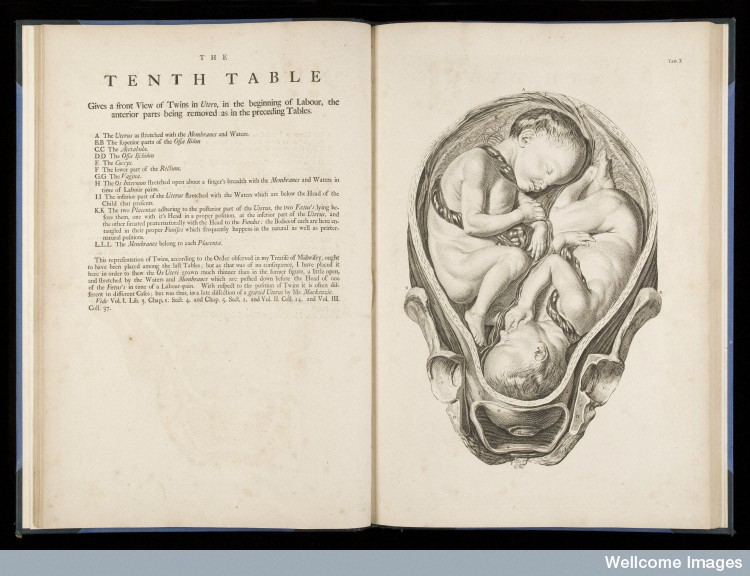

Great post, Jen! I really enjoyed it and very interesting. Was just wondering where the fabulous image of the twins in the womb comes from? Leah