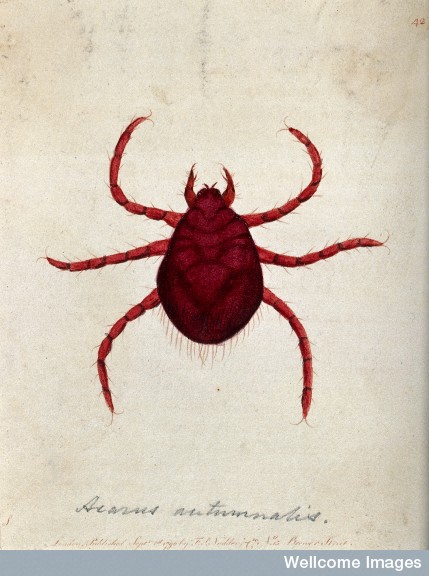

‘The Itch is a filthy Distemper infesting the External Parts of the Body universally, but more particularly the Joints, and between the Fingers’, wrote Thomas Spooner, author of a multi-edition treatise on the subject of ‘the itch’.1 Skin diseases and itchiness generally seem to be part and parcel of early modern life. Venereal diseases had reached almost epidemic proportions and syphilis manifests in skin lesions amongst its other symptoms, for example.2 Other things such as flea bites or the louse that Jen’s post the other week discussed could cause nasty itching. All manner of eczemas and other diseases also attacked the skin.  One highly contagious itchy disease was caused by the scabies or itch mite. This was generally referred to as having ‘the itch’ or ‘the scab’. Spooner explained that it didn’t matter where the itch started on your body first as it would soon spread and cover the entire body. Spooner cites seventeenth-century medic Thomas Willis who claimed that the itch was the most contagious of conditions after the plague. The itch spread by sharing beds, clothing and other linen, and medics knew that even after washing linen it could still cause re-infection. (Nowadays people are advised to boil-wash linen to kill the mites.) It was not understood to be caused by a mite, though, but instead scabies or ‘scabbiness’ was thought to follow on from a long-standing itch where the skin became infected or ulcerated, so while it arose from internal causes, it was still understood to be contagious.3 The itch was thought to be caused in the first place by an imbalance of humours in which a person had too much choler. Spooner described how people often didn’t seek out treatment promptly because they felt ashamed of having the itch or were worried it might be a symptom of something more serious. Scabies don’t discriminate by rank and clergyman Ralph Josselin noted having the scab five times in his diary. In March 1652 he noted how his children were suffering from the scab.4 Later, in February 1665 itchiness was getting Josselin down as he noted, ‘God good to me in manifold mercies, the scab a very great trouble to me, lord heal and help me, god good in his word, he essays to bring my heart to more inward seriousness with him, lord effect it, and let me live unto you’.5

One highly contagious itchy disease was caused by the scabies or itch mite. This was generally referred to as having ‘the itch’ or ‘the scab’. Spooner explained that it didn’t matter where the itch started on your body first as it would soon spread and cover the entire body. Spooner cites seventeenth-century medic Thomas Willis who claimed that the itch was the most contagious of conditions after the plague. The itch spread by sharing beds, clothing and other linen, and medics knew that even after washing linen it could still cause re-infection. (Nowadays people are advised to boil-wash linen to kill the mites.) It was not understood to be caused by a mite, though, but instead scabies or ‘scabbiness’ was thought to follow on from a long-standing itch where the skin became infected or ulcerated, so while it arose from internal causes, it was still understood to be contagious.3 The itch was thought to be caused in the first place by an imbalance of humours in which a person had too much choler. Spooner described how people often didn’t seek out treatment promptly because they felt ashamed of having the itch or were worried it might be a symptom of something more serious. Scabies don’t discriminate by rank and clergyman Ralph Josselin noted having the scab five times in his diary. In March 1652 he noted how his children were suffering from the scab.4 Later, in February 1665 itchiness was getting Josselin down as he noted, ‘God good to me in manifold mercies, the scab a very great trouble to me, lord heal and help me, god good in his word, he essays to bring my heart to more inward seriousness with him, lord effect it, and let me live unto you’.5

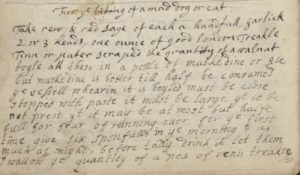

The Somerset Apothecary John Westover of Porch House, Wedmore sold medicated girdles for ‘the itch’.6 These products were his best-selling treatment and he charged 1 s 6 d for a girdle, but having bought one, you could return to have it re-medicated for a shilling, rather than buying a whole new one. In 1688 Joan Adams went to Westover for 2 girdles for the itch, but obviously didn’t have the money to pay for them at the time and so negotiated that she would pay Westover back at harvest time by labouring at haymaking on his land. Westover didn’t describe what he used in his girdle but Spooner explained that physicians prescribed girdles medicated with mercury (quicksilver) carried in an unguent. Rebalancing the humours was the standard early modern medical cure and so recommended for this disorder too, along with purging, sweating and washes made with tobacco or sulphur (brimstone). The wearing of a mercury girdle for a long time could cause side effects, and Thomas Spooner quotes at length from Francis Fuller’s Medicina Gymnasticia; or the Power of Exercise (1704), which he also appends to this volume of The Itch. Fuller described how after wearing a mercury girdle for several months for the itch which he had ‘accidentally’ caught. Fuller’s symptoms began a month after he discarded the girdle and included tingling fingers and generalised giddiness. The treatment might have been troublesome or even dangerous but it is clear that people were willing to try most things to be rid of debilitating itching. Spooner even gives an example from December 1717 in which of four apprentices who sought treatment from a local woman who gave each of them a tablet to cure the itch which killed them, much to the shock of the woman who hadn’t meant any harm!7 So while itching disorders were prevalent people did seek out methods to cure themselves, often with disastrous or ineffectual consequences.

_______________________________________

1 Thomas Spooner, A Short Account of the Itch (London, 1717), p. 1.

2 Linda E. Merions, ed., The Secret Malady: Venereal Disease in Eighteenth-century Britain and France (Lexington, KY: The University of Kentucky Press, 1997), p. 5.

3 Spooner, The Itch, p. 11.

4 Alan MacFarlane ed., Ralph Josselin, The Diary of Ralph Josselin, 1616-1683 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976), p. 274.

5 Josselin, The Diary, p. 515.

6 ‘The Casebook of John Westover of Wedmore, 1686-1700’, transcribed by William G. Hall

7 Spooner, The Itch, pp. 54-5.

© Copyright Sara Read, all rights reserved

First of all I would like to say superb blog! I had a quick question that I’d

like to ask if you don’t mind. I was interested to find out how

you center yourself and clear your thoughts prior to writing.

I have had a hard time clearing my thoughts in getting my thoughts out there.

I truly do take pleasure in writing but it just seems like

the first 10 to 15 minutes tend to be lost simply just trying to figure

out how to begin. Any ideas or tips? Kudos!

Thank you for your kind comment on the blog.

I think everyone is different when it comes to how and when they find it best to write. Some are better in the morning and some in the evening for instance. One tip I was told was to give yourself a time limit. Promise yourself that if you just do half an hour today then you can leave it and walk away until tomorrow. Often you find having given yourself permission to stop after a short time, you do just carry on. But knowing you don’t have to and that you have met your target can help.

All the best

Sara