Travelling and bathing

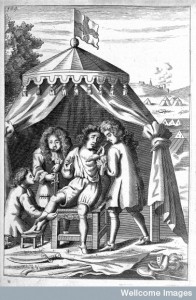

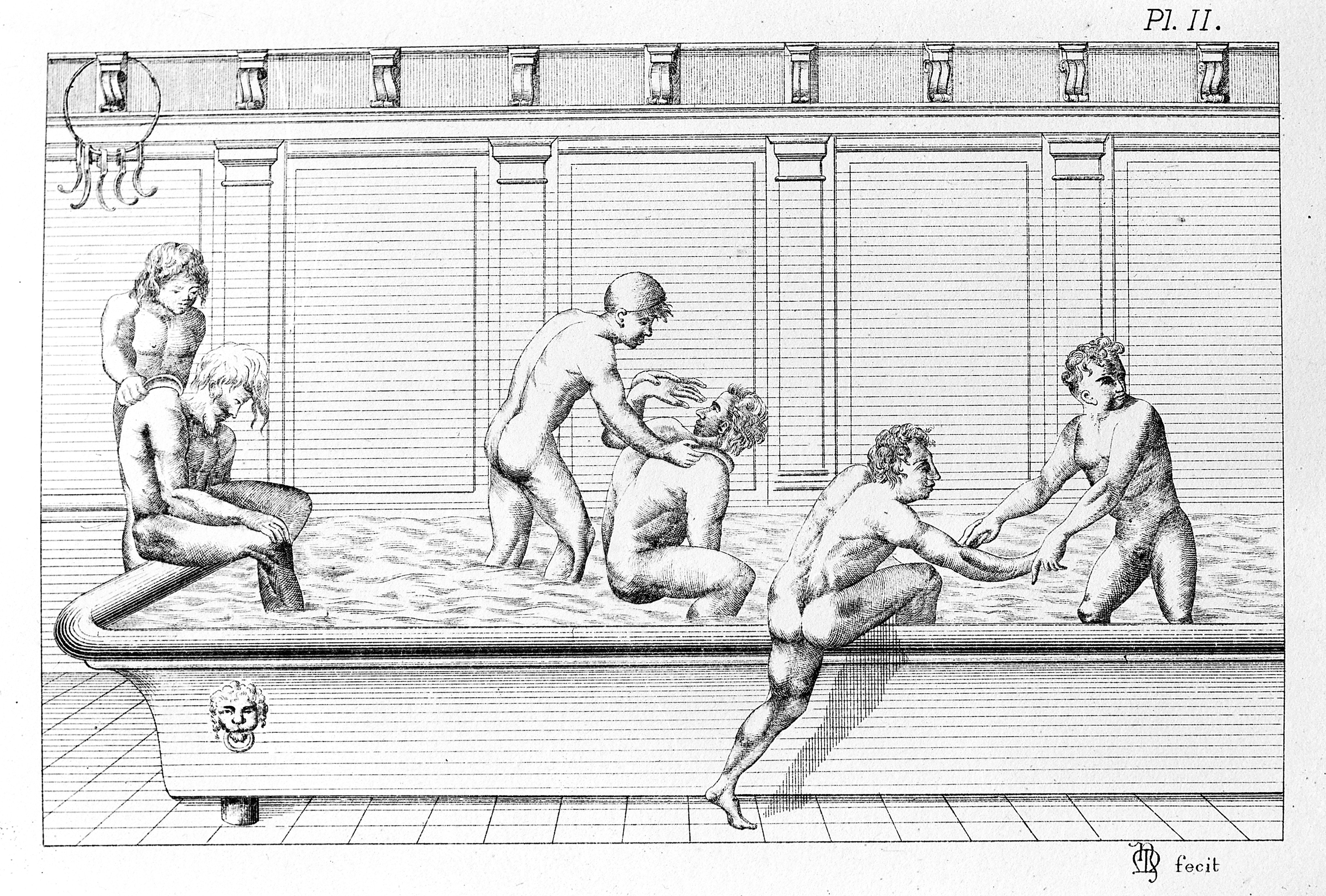

In June 1645 John Evelyn travelled from Rome to Venice. The journey left him extremely weary and so he decided to visit the ‘Bagnias’ to take a bath. He described the experience as follows:

[The bath] treat after the Eastern manner, washing one with hot & cold water, with oils, rubbing with a kind of Strigil [a curved blade to scrape away sweat], which a naked youth puts on his hand like a glove of seals Skin, or what ever it be, fetching off a world of dirt, & stretching out ones limbs, then claps on a depilatory made of a drug or earth they call Resina, that comes out of Turkey, which takes of all the hair of the body, as resin does a pig’s. I think there is orpiment & lime in it , for if it lie on to long it burns the flesh.

A risky business

This was clearly an intriguing experience for Evelyn and one that was beneficial in removing dirt from his travel stained body. However, bathing was a risky business. I have written before about how Evelyn often mentioned that cold deeply affected his body while on his travels through Europe. This moment of bathing was no different. Evelyn declared that he did not escape unscathed,

The curiosity of this Bath, did so open my pores that it cost me one of the greatest Colds & rheums that ever I had in my whole life, by reason of my coming out without that caution necessary of keeping my self warm for some time after.

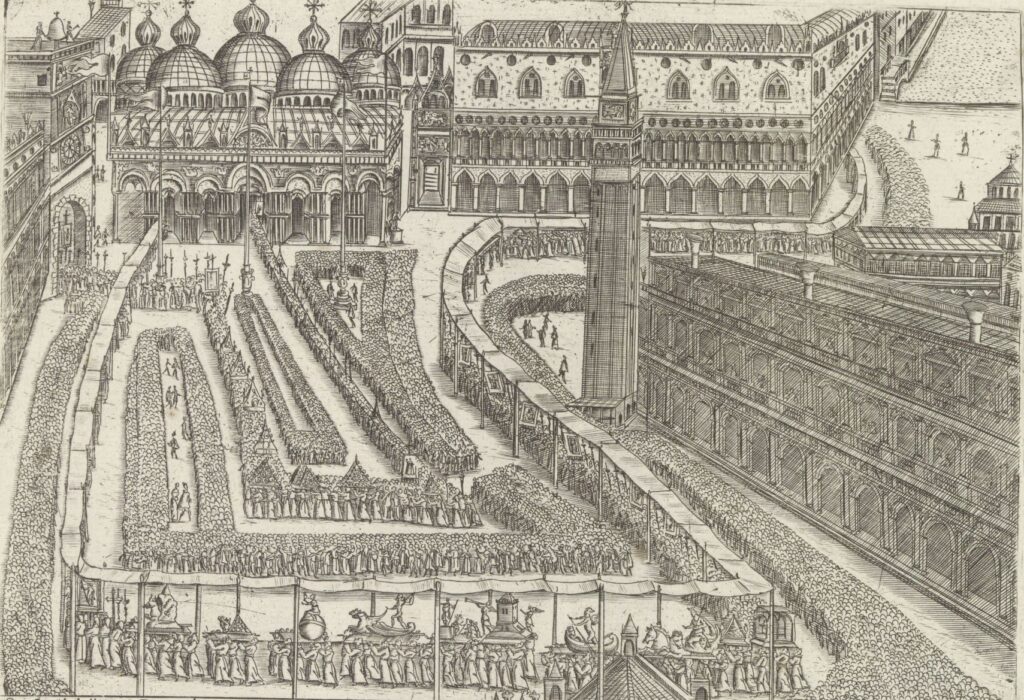

As Evelyn suggested here, most people believed that bathing opened the pores of the body making it permeable and porous and therefore susceptible to the threats of the outside world. It was important that those who bathed kept their bodies warm to stop the cold seeping in. Evelyn didn’t do this instead he ‘immediately began to visit famous Places of the City’. In running about the city to see the tourist hot spots Evelyn claimed that he was following the crowd who ‘do nothing else but run up & down to see sights’.

Procession across St. Mark’s Square in Venice, anonymous, 1610 (Rijksmuseum)

Remedying a rheum

Culpeper’s School of Physick (1659) described a ‘Rheum’ as a distillation of humors and excrements from the head or the brain into other parts of the body. These were often shed from the body by the mouth, but also by the nose, ears or eyes if they were too copious. Falling on the lungs a rheum caused hoarseness of breath, coughing and pain. The book explained that the condition was not serious if it affected the nose, but was more serious if it fell on the lungs. So perhaps, despite his claims, Evelyn’s condition was quite mild, albeit frustrating.1

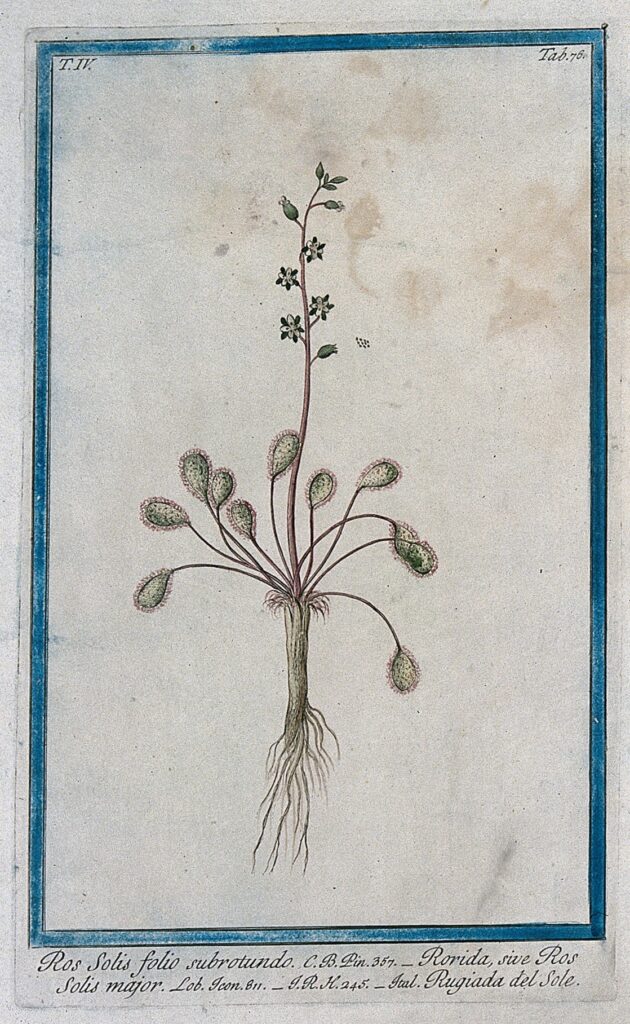

Evelyn doesn’t mention taking any specific remedy to ease his condition. But we might imagine that he took something to reduce his symptoms while he explored the city. He may have opted for Rosa Solis (also called Sun-dew). This plant was describe as growing in bogs and wet places, that retained moisture on its surface no matter how brightly the sun shone. An eighteenth-century edition of Culpeper’s English Physician declared that it was particularly good for those that had a ‘salt Rheum distilling on the Lungs’. He recommended that a distilled water of the plant would cure this as well as helping wheezing, shortness of breath, and a cough.2

We might rightly worry about Evelyn’s health since he claimed to have caught one of the worst colds of his life. But the lack of detail about any attempts to remedy his condition and his description of gallivanting around the city for several days without much mention of any symptoms suggests that despite his hyperbole he was perhaps more struck by the fact that he caught a cold bathing, than by his cold itself.

_________________________________________

- Culpeper’s school of physick, or, The experimental practice of the whole art (London, 1659), p. 389.

- The English Physician Englarged (London, 1759), pp. 282-3.