Gender reveal parties, which started some time in the 2000s, have become increasingly elaborate and Instagram worthy. Some excessive stunts have even caused raging wildfires. When I was younger these parties weren’t around but I do remember old wives tales of practices that were supposed to reveal the gender of the still developing foetus. In particular I remember the idea of hanging a ring on a thread above the mother’s belly, if it swung in a circle then it was a boy, if moved back and forth it was a girl.

Without the aid of modern ultrasound equipment early modern men and women had no way of knowing if they were expecting a baby boy or a girl. Gender remained concealed rather than revealed. However, this didn’t stop various medical texts from encouraging practices to help expectant couples try to get what they wanted.

Seventeenth-century suggestions

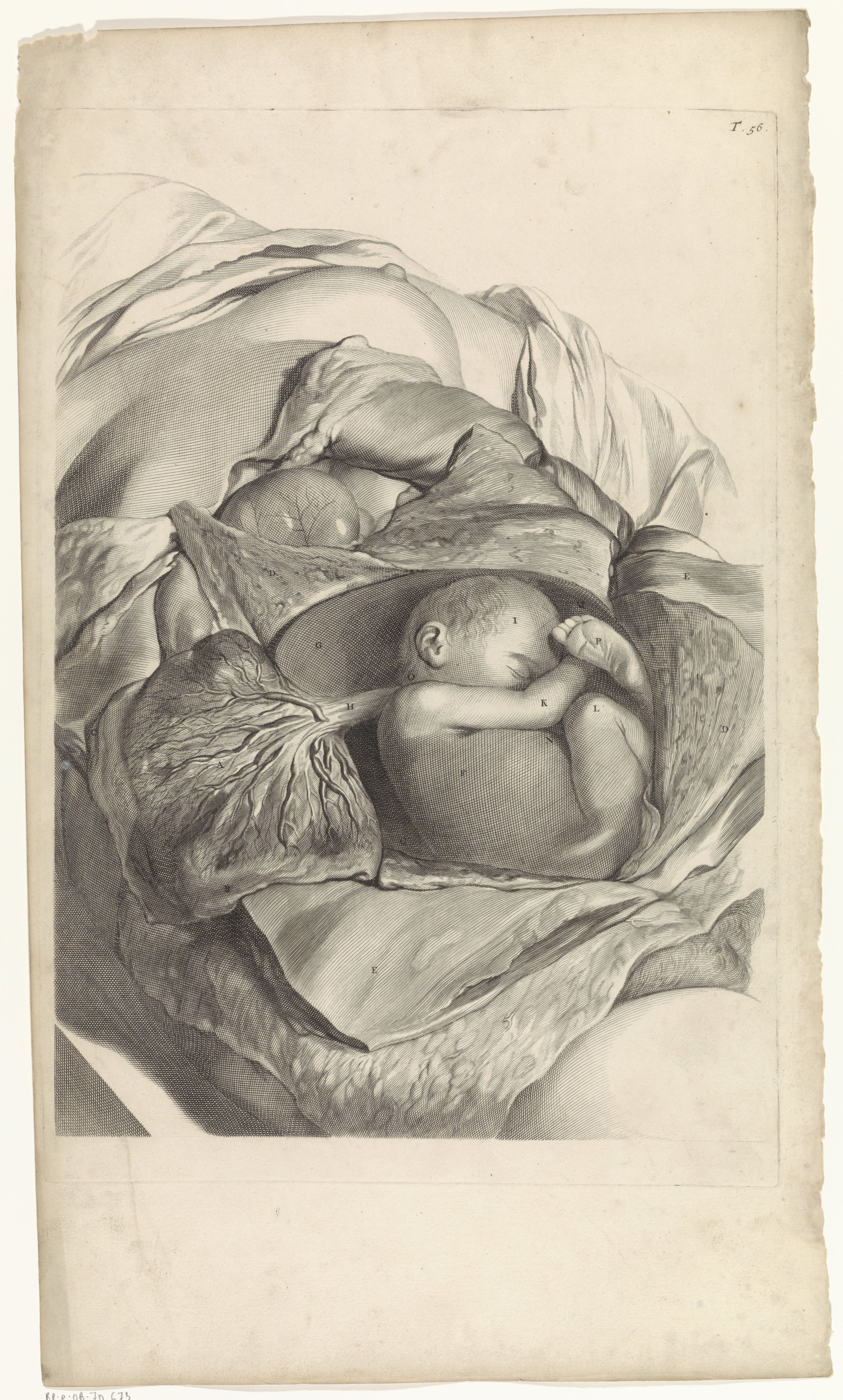

Anatomical Study of the Inside of the Uterus and a Fetus, Pieter van Gunst, after Gerard de Lairesse, 1685

Aristoteles Masterpiece, the widely read sexual manual of the late seventeenth century. Encourage women to lie down on their right side, so that the man’s seed (sperm) would fall into the right side of the womb. This would ensure the greatest amount of ‘generative heat’ which was crucial for creating a boy. To further improve these chances the woman should ‘keep themselves warm, and without much motion. This the author explained ‘rarely misses to answer the expectation’ of getting a boy.

The time of the year could also help if you were hoping to have a boy. Conceiving when the sun was in Leo, or in Virgo, Scorpio or Sagittarius would improve your chances. Early modern medical writers believed that the best time to conceive was just after menstruation, as this was the moment at which the womb was cleansed and ready for gestation. The author of Aristoteles Masterpiece therefore recommended that for a boy the couple should aim to conceive from the 1st to the 5th day after menstruation, between the 8th and the 12th days it was more likely a girl would be conceived.

Seventeenth-century signs

Jane Sharp’s The Midwives Book (1671) included a chapter devoted to the ‘signs that a woman is conceived with Child, and whether it be a son or a Daughter’. Sharp acknowledged that it was a difficult thing to establish but that with a boy the mother would be a better colour and her right breast would swell more than the left. Likewise if the child was a boy it would be felt to move on the right first.

Sharp also explained that if a woman standing up from a chair used her right foot first and leant on her right hand then she was carrying a boy. If interested parties wanted further evidence then some drops of breast milk should be placed in a basin of water. If the milk sank the woman was carrying a boy, if it floated it was a girl.

Eighteenth-century advice

In the early eighteenth century Nicholas Venette’s treatise Conjugal Love Reveal’d was translated into English, from the original French. The book, like Aristotle’s Masterpiece, provided information on ‘Whether there is an Art in getting Boys or Girls‘. Venette explained that some men had a great desire to perpetuate themselves and that the happiness of kingdoms and families sometimes depended upon the appearance of a male heir. Having hinted that there were ‘rules’ that could be established to help meet this desire, Venette pointed out that whether this art existed was the ‘most difficult in all Physick’.

Venette explained that women’s eggs were ball ‘as big as small Pease’. These were ‘impregnated by the Man’s seed’. Within this ball there was then its ‘liquors’ that formed the ‘Bud of an Infant’. Boys were made from those with ‘hot, dry and thick Matter, full of Fire and Spirits, with close pores and firm parts’. Girls were made of ‘less hot, moister, and more delicate’ matter.

He contradicted the author of Aristotle’s Masterpiece, noting that ‘`Tis not the Womb that is the principle cause of Males or Females’. The womb, he explained, was only a place in nature where children were formed. It only appeared to be hotter on the right because it was imparted with heat from the liver. Dissections, he claimed, had shown that male and female children were born on either side of the womb.

Rejecting accepted advice

He also contradicted other popular ideas. He explained that menstrual blood had no part in determining the sex of the child because by the time blood flowed to nourish the developing foetus it had already received its sex. However, he later listed as a ‘rule’ that women conceive boys more readily after moderate menstruation and girls after excessive menstruation. Heavy flow suggested that a woman had a moist constitution unsuitable for producing boys. So he was not entirely consistent in this regard.

He also argued against the idea that women’s imaginations were responsible. He questioned the logic of the idea, stating,

for how many Women are there that bear only Girls, and cannot have Boys, though their imagination runs perpetually, and is as if ’twere stuffed with the Idea’s of the latter’.

He likewise rejected the notion that astrological influence was involved. Having explained to his readers that the only influence on the sex of the foetus was the ‘matter’ it was made from. He proceeded to inform his readers of the best ways to make matter that would result in male children. The main way to achieve this was to eat and drink ‘jucy things, hot and full of Spirits’, as well as ‘the flesh of lascivious animals’. This food and drink would create warm blood that would then make strong and warm ‘seed’ or ‘matter’ for conception. Many of these foods were also used as aphrodisiacs as I have discussed before. However, it was important not to eat these foods to excess as this would cause slugging digestion and make matter and seed that was lacking in heat and spirits.

He also argued that too much love making would reduce the chances of conceiving a boy. This drained the body of its vital heat and caused the production of feeble seed. That this was true, he explained, was evident because newly married young couples who ‘Caress so desperately’ in the first days of marriage tended to produce only girls, meaning there were more first born girls than boys. Better, he said, was to only have sex three or four times a month.

Subtle signs

Venette suggested that there might be some tell-tale signs by which the mother, and other interested parties, could establish the gender of the child growing in the womb. He said that because the nature of men was hotter and drier – shown in men’s desire to take part in war and great affairs – women who were carrying a boy-child would be ‘for the most part fresh coloured’ and do ‘better’ in their pregnancy. This was because the heat of the developing boy offset and corrected the mother’s naturally cold disposition – that was inclined to fatigue. Carrying a girl meant a woman’s natural coldness was augmented by the chill of the female child and so she would be ‘sickly’ throughout her pregnancy.

It is apparent then that much thought was put into conceiving a boy or a girl in the early modern era. And despite the difficulties of knowing the sex of the growing foetus those like Venette were convinced that there was ‘an Art to get Boys or Girls’ and that if people diligently followed the rules then ‘they will sooner get a Boy than a Girl’.

Anonymous, Aristoteles Masterpiece (London, 1684)

Jane Sharp, The Midwives Book (London, 1671)

Nicholas Venette, Conjugal Love Reveal’d (London, 1720)

Interesting article and I loved the way you gave it a twenty-first century example.

Thanks Ursula!