Early modern medical treatises often included remedies for those who were finding themselves a little forgetful and for those who wanted to avoid having a muddled memory. This is something I could definitely use, I sometimes feel like my head is a colander with all the useful information trickling out and getting away from me. These remedies took numerous forms, not all of which make immediate sense.

Some remedies were rather straightforward, one offered in Peter Leven’s Pathway to Health (1596) was simply, ‘Take Mugwort, and lay it in white Wine, and then take it and distill it, and use to drinke of it fasting, and it shall preserve the memory’.1

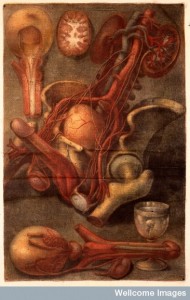

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

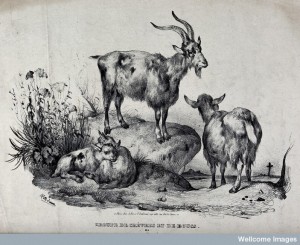

If drinking wine wasn’t appealing, Levens also offered remedies that were breathed in as fumes: ‘Take Rue, red Mints, Oyle olive, and with very strong Vineger let they nostrils be holden over the smoke therof. Also burne thine owne haire, and mingle it with vinegar and a little pitch, and apply it to thy nostrils, for it wonderfully stirreth and quickneth the persons diseased with forgetfulness.’2 A similar remedy involved inhaling the fumes of a young goat’s skin burnt – ‘the fume of a Kidds skin dooth quicken forgetfull persons’.3

Inhaling a range of smelly substances is perhaps not that difficult to understand for modern readers. After all a range of aromatherapy oils are advertised as able to help our mental state by relaxing or focusing our mind for academic activities. Smells in the early modern period were thought to exist in many different forms including smokes, fumes, balms, waters and powders.4 In terms of their medical properties, many early modern medical writers including Helkiah Crooke believed that smells were invisible particles that penetrated the organs in the nasal cavity and touched the brain.5 By touching the brain these substances transferred their humoural properties to the body; as material particles, smells contained the humoural properties of the substances from which they originated. Smells were then able to create change within the body by affecting the brain. Holly Dugan, in her book The Ephemeral History of Perfume, has explored the numerous ways in which these substances were used in early modern culture. Smells were widely utilised in medical treatments for a range of disorders and problems, including, as we can see here improving the mind and preventing forgetfulness.

Other remedies appear a bit more counter-intuitive, like this one to be applied to the soles of the feet: ‘Take and grind Musterseede with Vineger, and rubbe it mightily on the plants of the feet: and it doth quicken the memory of such persons as have been long time sicke, and will stir them up from all kind of forgetfulnesse of memory, and maketh them mindfull of such business that they take in hand.’6

Remedies for other illnesses were also applied to the feet, although it is not apparent why they were applied in this way. Walter Bruele’s book recommended applying oil of violets to the soles of the feet and the temples to cause sleep, while Oswold Croll’s medical text advised applying the fat of a pike-fish to the soles of child’s feet to cure a cough.7

It is not obvious in many of these remedies whether they were designed to treat mild feelings of confusion and, what we might call, everyday lapses in memory. In some cases authors suggested that these remedies were to prevent the deterioration of mental capacities associated with ageing. One was, for example, ‘to keep good memory’, or, as above, to help ‘the memory of such persons as have been long time sicke’. It seems though that medical writers offered remedies for either instance. Yet it is perhaps interesting that Levens offered one-off remedies, rather than a course of treatment, which would of course have required the patient to remember to take the medicine at regular intervals.

_______________________

1. Peter Levens, A Right profitable booke for all Diseases called, the Path-way to health … (London, 1632), p B2r

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid, p. 6.

4. Holly Dugan, The Ephemeral History of Perfume (Baltimore, 2011), p. 5.

5. Cited in Dugan, The Ephemeral History of Perfume, p. 12.

6. Peter Levens, A Right profitable booke for all Disesases, p. 4.

7. Walter Bruele, Praxis medicinae, or, the physicians practice (London, 1632), p.33. and Oswald Croll, Bazilica chymica, & Praxis chymiatricae, or, Royal and practical chymistry in three treatises (London, 1670), p. 61.