For those readers living in Britain stories of men and women faking illness or disability in order to receive benefits from the state welfare system will be familiar, recited in the tabloid newspapers and even on television. These stories often provoke anger and disgust as people rail against the unfairness of the system and empathise with those who really do need help and miss out.  The use of such tricks, however, is far from a modern invention.

The use of such tricks, however, is far from a modern invention.

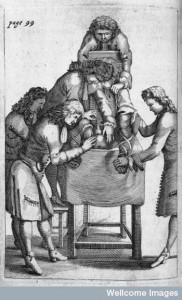

The 1634 edition of the French surgeon Ambrose Paré’s treatise (pictured here) included several rather gruesome stories of fakes and frauds who pretended to be suffering from terrible illnesses and disorders in order to beg for charity from passers-by. Paré introduced this topic by warning of the many ways in which men and women acted to deceive honest charitable people. He emphasised that these beggars were not desperate but were wholly villainous and that their initial behaviours could lead them to more criminal actions, such as child abduction:

‘Some there bee, who not content to have mangled, and filthily exulcerated their limbes with causticke herbs, and other cauteries; or to have made their bodies more swolne, or else leane, with medicated drinks; or to have deformed themselves some other way, but from good and honest Citizens, who have charitably relieved them, they have stollen children, have broken or dislocated their armes and legges, have cut out their tongues, have depressed the chest, or whole breast, that with these, as their owne children, begging up and downe the country, they may get the more reliefe, pitifully complaining that they came by this mischance by thunder, or lightning, or some other strange accident.’1

Paré continued by relating some particular examples of the deceits performed by women (warning these do not make for the most pleasant of reading). The first story explained how,

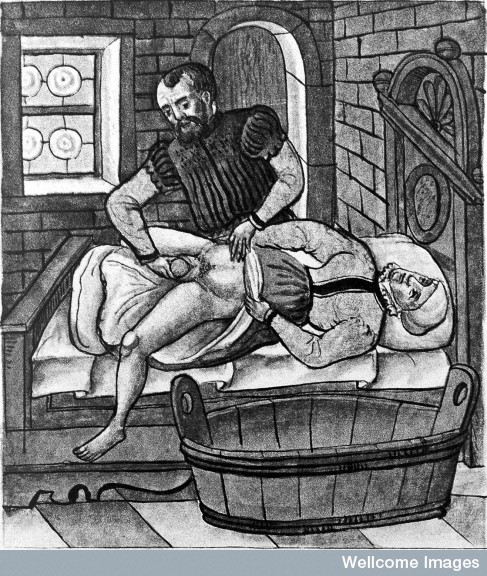

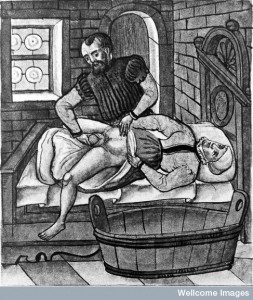

‘Dr. Flecelle, a Physitian of Paris, entreated me to beare him company to his country house at Champigny, foure miles from Paris. Where as soone as wee arrived, and were walking in the Court, there came presently to us a good lusty well flesht manly woman, begging almes for St. Fiacre sake, and taking up her coat and her smocke, she shewed a great gut hanging downe some halfe a foot, which seemed as if it had hanged out of her fundamnet [anus], whereout there dropped filth like unto pus, which had all stained her legges and smocke, most beastly and filthy to looke upon. Flecelle asked her how long she had beene troubled with this disease: she answered that it was foure yeeres since she first had it. Hence he easily gathered that she plaied the counterfeit: for it was not likely that such abundance of purulent matter came forth of the body of so well flesht and coloured a woman; for she would rather have been very leane and in a consumption. Wherefore provoked with just anger, by reason of the wickednesse of the deceit, he run upon her and threw her downe upon the ground, and trod her under his feet, and hit her divers blowes upon the belly, so that he made the gut which hung at her, to come away, and by threatning her with more grievous punishment, made her confesse the cozenage, and that it ws not her gut, but of an oxe, which being filled with blood and milke, and tyed at both ends, shee put the one of them into her fundament, and let the filth flow forth at very little holes.’2

A second similar story explained how,

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

‘Not very long agoe, a woman equally as shamelesse, offered herselfe to the overseers of the poore of Paris, entreating that she might be entred for one of their Pensiosers, for that her wombe was fallen downe by a dangerous and difficult birth, wherefore she was unable to worke for her living. Then they commanded that shee should be tryed and examined, according to the custome, by the Chirurgians which are therefore appointed. Who seeing how the whole business was carried, made report she was a counterfeit for she had thurst an oxes baldder, halfe blown and besmeared with beastly blood by the neck, whereto she had fastned a little spunge, into the necke of her wombe, for the spunge being filled and swollen up by the accustomed moisture of the wombe, so held up the oxes bladder that hanged thereat, that she might sagely goe without any feare of the falling of it out, neither could it be pulled forth but with good force. For this her device shee was put into Prison, and being first whipped , was after banished.’3

These stories reveal that men and women would go to quite bizarre lengths in order to beg for money more effectively. They also, however, emphasise the role physicians and surgeons were expected to play in revealing the truth of such cases. It was their knowledge of the body that allowed them to see through the rouse and discern the truth behind the lies.

They also highlight the more visible nature of early modern bodies – it was not, as far as this text makes out, unusual for the bodies of the poor, or even the fundament of sick person, to be open to the gaze of passers-by.

They also highlight the more visible nature of early modern bodies – it was not, as far as this text makes out, unusual for the bodies of the poor, or even the fundament of sick person, to be open to the gaze of passers-by.

Finally, these stories reveal that anger and frustration at those who lie and cheat in order to gain something for nothing is enduring. Dr Flecelle’s particularly violent reprisal of the Champigny woman is related without any sense that this was an excessive or unexpected response. Indeed Paré noted that his reprisal was provoked by ‘just anger’. Moreover, just like today, it was believed that people would be interested in reading about such cases – even if in this case it was a limited audience of medical readers.

To find out more about the idea of worthy and unworthy paupers in the early modern era read Brodie Waddell’s piece on Rich Beggars over at the Many Headed Monster.

______

1. Ambrose Paré, The Workes of that famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, Translated out of Latine and Compared with the French by Th[omas] Johnson (London, 1634), p. 994.

2. Ibid, p. 994-5.

3. Ibid, p. 995.

© Copyright Jennifer Evans, all rights reserved.

Monstrous humans and monstrous birth narratives were often highly fictionalized or mere legends, told for various reasons. However, other narratives, especially the broadsheets or first-hand accounts by doctors, often contain what look like reliable accounts of the family and their reasons for putting the infant (or themselves, if adult) on display. My own favourite is an elderly widow, of more than adequate means, who simply wanted to see London.

Those parents who put an infant or stillborn on display, at an inn, may well have been not far removed from the fake beggars, even though they were telling the truth. They would, however, need to be respectable, if they were not to be subjected to invidious interpretations of their misfortune, in terms of providential punishment, rather than the birth being a natural marvel or a sign to the nation as a whole.

Definitely, I find the historiography on the changing notions of ‘scientific’ (if we want to call it that) or ‘reliable’ reporting about these things and the relationship to changes going on at the Royal Society and the influence of Francis Bacon really interesting.