Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

As advent is underway I thought I would enjoy a brief excursion and write about something seasonal. Every year as the Christmas season approaches I look forward to making, baking and eating LOTS of mince pies. They are my favourite festive treat. Perhaps as expected, a mince pie was something a little bit different in the eighteenth century.

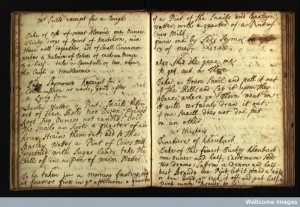

This recipe ‘To make mince pies’ appears on a loose sheet of paper, one of 50 loose sheets which were saved alongside, and many incorporated into, the manuscript recipe collection Wellcome MS 8468. This recipe collection was transcribed by several members of the Sheldon family, of Weston, Warwickshire, in the eighteenth century.

Take three Pounds of the inside of a Sirloin of Beef seven Pounds of Suet seven Pounds of Currens well washed two pounds of Raisins of the Sun Stones. three ounces of Cinnamon Cloves & mace, the paring of an Orange, & Lemon Sliced small & the juce Squeez’d six Pippins Chopped in half an ounce of Carraway Seeds Steeped all night in a pint of Sack Sweetened to your Palate, add what Sweetmeats Spice Brandy or wine which you please

It is best made of tongue in place of Beef.1

There was no suggestion from the title of this recipe that associated particularly with the festive season. But an edition of the Gentlman’s Magazine from December 1733 included an essay On Christmas Pye, which argued that ‘this Dish is most in Vogue at this Time of Year, some think is owing to the Barrenness of the Season, and the Scarcity of Fruit and Milk, to make Tarts, Custards, and other Desserts, this being a Compound that furnishes a Dessert itself.’2

The author went on to explain that he thought ‘it bears a religious kind of Relation to the Festivity from which it takes its Name’. This, he pointed out, was a contentious issue as it met with ‘Zealous Opposition’ ‘from the Quakers, who distinguish their Feasts by an heretical Sort of Pudding, known by their Names, and inveigh against Christmas Pye, as an Invention of the Scarlet Whore of Babylon, an Hodge-Podge of Superstition, Popery, the Devil and all his Works.’3

The author of this essay, who styled himself Philo-Clericus, was particularly upset by the claim that the Clergy should not indulge in mince pies and eloquently proclaimed why, contrary to these assertions, mince pies were the ideal food for clergymen:

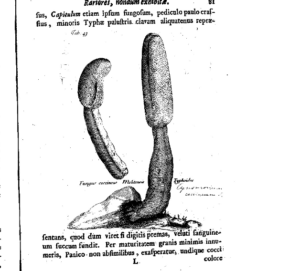

‘This must be allow’d unfair Treatment. But if in the Composition of Neat’ Tongue be used instead of the Sirloin; and if that Part of our Bodies receives a greater Proportion of the Nutriment, which answers to that Part of the Creature whereof we eat, then this Sort of Food is the properest in the World for the Clergy, as it must be a Strengthner of the great instrument of Speech, the Volubility of whose Motion is of the greatest Consequence both to themselves and the Publick; but when improved with Plumbs, &c. [etc.] it must sweeten the Speech into the most perswasive Eloquence.’4

Although, sometimes thought to have been rather unfashionable by the eighteenth century, Philo-Clericus draws upon the idea of sympathy, or the doctrine of signatures, to make his argument about the suitability of the mince pie as a food for the clergy. In this understanding foods which bore a similarity to a body part were thought to enhance it – in my own research this most notably appears as the eating of animal genitalia to strengthen sexual vigour. Here the consumption of sweetened tongues makes the clergymen more eloquent and more persuasive. I can, perhaps, hope then as I tuck into my own mince pies that they will help make me more eloquent. The use of this idea suggests that understandings about the body creep into a very wide range of discussions, discourses and debates that at first might appear to have very little to do with the body. Bodily experience is crucial to how we understand our experiences and can be crucial to understanding the past.

[If you would like to read more about the history of the mince pie there are several articles including this article which draws on Samuel Pepys’s descriptions of Elizabeth’s pie making]

__________________

1. London, Wellcome Library, MS 8468.

2. Gentleman’s Magazine, Vol. 3 Dec 1733, p. 652

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid, p.653.

2 thoughts on “A Festive Food”

Comments are closed.