Katie Aske returns this week in her second guest blog post – the first one is here . This week Katie is discussing beauty spots!

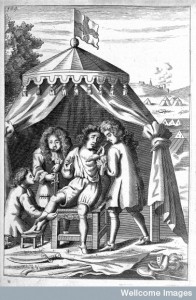

The beauty spot is the trademark of the eighteenth-century’s powdered beauties, both male and female. To achieve a beauty spot when one did not occur naturally, people took to wearing false ones made from velvet and stuck on to the face.

In Antoine Le Camus’ Abdeker: or the Art of Preserving Beauty (1754), after seeing a fly land on Fatima’s beautiful face, Abdeker remarks, ‘I think its Blackness sets off the Lustre of the Vermillion [and] makes your Eye look more lively and amourous’.1 However, despite the intention of highlighting the paleness of the wearer’s skin, the beauty spot or patch could appear similar to a medical plaster, and this meant their reputation was as ranging as their shape. Patches were not only the height of fashion, but could be attributed to the concealment of scars or signs of disease. It is this dichotomy that John Bulwer discusses in Anthropometamorphosis: Man Transform’d or, the Artificiall Changling (1652):

they that suppresse and smother [their sins] by paintings, and unnaturall helps to unlawfull ends, do not deliver themselves of the plague, but they do hide the markes and infect others, and wrastle against Gods notifications of their former sins. The invention of which Act of Palliation of an ascititious deformity against Gods indigitation of sin, is imagined one reason of the invention of black Patches, wherein the French shewed their witty pride, which could so cunningly turne Botches into Beauty, and make uglinesse handsome; yet in point of Phantasticalnesse we may excuse that Nation, as having taken up the fashion, rather for necessity than novelty, in as much as those French Pimples have need of a French Plaister.2

The adoption of this French fashion, which reached its height under Louis XVI’s reign, meant that on the one hand these patches represented luxury; they depicted status and wealth, were available from perfumeries and often made from expensive coloured fabrics. On the other, they became associated with flirtation, licentious behaviour and the treatment venereal disease. For example, Peter Wagner suggests that the beauty patch became codified, with the position of each patch indicating a secret message to the viewer:

women who wanted to create the impression of impishness stuck them near the corner of the mouth; those who wanted to flirt chose the cheek; those in love put a beauty spot beside the eye; a spot on the chin indicated roguishness or playfulness, a patch on the nose cheekiness; the lip was preferred by the coquettish lady, and the forehead was reserved for the proud.3

Morag Martin’s work on French cosmetics suggests that these patches, also known as mouches, had various names depending on the position on the face: the ‘assassin’ (forehead); ‘gallant’ (cheek) and ‘coquette’ (lips).4 In England the position took on a political meaning, with the Whigs and Tories adopting opposing sides of the face.5

But the position of the patch was not always in the wearer’s control. Roy Porter claims in Bodies Politic that many beauty products, particularly the fashionable patches, were made to mask the signs of disease, small pox and syphilis in particular.6 According to N. F. Lowe, some medical treatments required skin plasters to ‘hold a curative unction in place’.7 Lowe suggests that the treatment for the French pox was often mercury-based, and it could be ‘mixed with turpentine in a mortar until a brown or black powder was obtained [and] when applied to the sore it could resemble a beauty spot’.8 William Hogarth is a particularly prolific example for making the connection between cosmetic beauty patches and the disguise and treatment of syphilis. They are present in many of Hogarth’s works, and can be seen gracing the faces of numerous men and women in A Rake’s Progress (1733), Morning (1738) and in A Harlot’s Progress (1731–32); as the fresh-faced beauty Moll Hackabout descends into the world of prostitution, her face becomes increasingly blotted with black patches.

While cosmetics and medical treatments enjoy common ground, Caroline Palmer notes the instability they cause to the social hierarchy. She suggests ‘cosmetics were used, not only by women of dubious repute, but also by ladies – and even gentlemen – of status’.9 Cosmetics clearly played their part in connecting the worlds of fashion and promiscuity, but the beauty spot is particularly interesting. On one face, like Moll Hackabout’s, the patch is symbolic of her sexual exploits and medical treatment. On another, it can indicate their status, wealth and even their marital status.

The patch, in its surge of popularity, managed to dictate a century’s standard of beauty, and at the same time, become a recognised symbol of sexual promiscuity.

Dr Katie Aske completed her Doctoral thesis at Loughborough University in 2014. It considered the meaning of beauty in the Eighteenth Century. Her work analyses the role of physiognomy and social stereotypes in the interpretation of the beautiful body. She also has a particular interest in the cosmetic practices of the eighteenth century. She has published several articles on beauty and physiognomy,

Dr Katie Aske completed her Doctoral thesis at Loughborough University in 2014. It considered the meaning of beauty in the Eighteenth Century. Her work analyses the role of physiognomy and social stereotypes in the interpretation of the beautiful body. She also has a particular interest in the cosmetic practices of the eighteenth century. She has published several articles on beauty and physiognomy,

_______________________________________

1 Antoine Le Camus, Abdeker: or the Art of Preserving Beauty (London: A. Millar, 1754), p. 150.

2 John Bulwer, Anthropometamorphosis: Man Transform’d: or, the Artificiall Changling, 2nd edn (London: William Hunt, 1653) pp. 272–73.

3 Peter Wagner, ‘Representation in William Hogarth’, in Hogarth: Representing Nature’s Machines, ed. by Frédéric Ogée, Peter Wagner, David Bindman (Manchester: Manchester University Press), pp. 114–15. Wagner refers to the work of German sexologist Eduard Fuchs for these details.

4 Morag Martin, Selling Beauty (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), p. 15.

5 Martin, Selling Beauty, p. 15. Joseph Addison notes this connection in The Spectator, Saturday 2 June 1711: ‘I found that the body of Amazons on my right hand were Whigs, and those on my left were Tories’.

6 See Roy Porter, Bodies Politic: Disease, Death and Doctors in Britain, 1650–1900 (London: Reaktion Books, 2001), p. 78.

7 N. F. Lowe, ‘The Meaning of Venereal Disease in Hogarth’s Graphic Art’, in The Secret Malady: Venereal Disease in Eighteenth-Century Britain and France, ed. by Linda Evi Merian (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1996), pp. 168–82 (p. 179).

8 Lowe, ‘The Meaning of Venereal Disease in Hogarth’s Graphic Art’, pp. 168–82 (p. 179).

9 Caroline Palmer, ‘Brazen Cheek: Face-Painters in Late Eighteenth-Century England’, Oxford Art Journal, 31, 2 (2008), 195–213 (p. 199).

(c) Dr Katie Aske, 2015, all rights reserved.

On the decision to include beauty patches in 17th-century painted portraits (some English ones, but particularly Dutch ones), see Karen Hearn, “Revising the Visage: Patches & Beauty Spots in 17th-Century English & Dutch Painted Portraits”, in Huntington Library Quarterly, vol.78, no.4, winter 2015/16, pp.809-823.