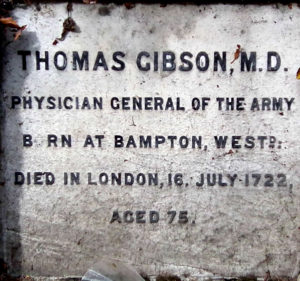

The name of Dr Thomas Gibson (1648/9–1722) isn’t one with much impact outside those studying the history of medicine, yet his story is one full of interesting details. Gibson was born in High Knipe, in the parish of Bampton, Westmorland.1 This is near Penrith in modern-day Cumbria.

Gibson’s ODNB entry and his obituary in the Munk’s Roll record that ‘he is stated in the Annals to have been created doctor of medicine by the archbishop of Canterbury, 16th May, 1663’, which seems extraordinary for a fourteen-year-old boy, let alone one from rural Cumbria. When he was 22, Gibson was ‘admitted ad eundem [given an honorary degree] at Cambridge, 5th October, 1671′ and so gained the title MD.2 This was awarded only a few months after his entry to St John’s College. After Cambridge, Gibson travelled to Europe where he ‘graduated doctor of medicine at Leyden, 20th August, 1675′, and [he] was admitted a Licentiate of the College of Physicians 26th June, 1676’.

Leiden University, founded in 1575, was a centre of excellence in medical training in the early modern period and boasts many famous alumni, so it is natural that Gibson would gravitate there to complete his medical studies. Gibson was admitted ‘as an Honorary Fellow of the College of Physicians 30th September, 1680’. However, Gibson was a Presbyterian and his faith was one of the reasons he was ‘removed from the list of fellows of the College of Physicians when the college received a new charter under James II in 1687’. He was reinstated after the Glorious Revolution in 1688 which saw James II usurped by the joint reign of his son-in-law and his daughter, William and Mary.

In the mid-1680s, Gibson married his first wife, Elizabeth (1646–1692) who was a widow from Stanstead St Margaret’s, Hertfordshire. Thomas was Elizabeth’s third husband and in her will she left her lands in Herts to him, but requested to be buried in her home church alongside her mother and her late son (her only child was from her first marriage).3 Gibson married his second wife, Anne (1659–1727), in June 1698. Anne was the granddaughter of the former Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell, the sixth daughter of Richard Cromwell, also, briefly, Lord Protector. He had no children. The antiquarian Thomas Hearne mentions Gibson in relation to his second wife a couple of times.4

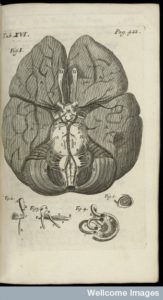

Thomas Gibson is best known for his book The Anatomy of Humane Bodies Epitomized (London, 1682), a book he

claimed to have been initially reluctant to write. The book is essentially an expanded and updated version of Alexander Read’s earlier text, The Manuall of the Anatomy of the Body of Man (several editions from 1638), but it was significantly revised as Gibson explained in his opening address to the reader. In this address, Gibson also felt obliged to defend his decision to write a book like this in the vernacular. Firstly, he said it was appropriate since Read brought out his text in English, but also because doing this would

avoid the injury of a paltry Translator, if it should be well accepted. For we see there is no Man that publishes any thing in the Latin tongue, that is received with any applause, but presently some progging Bookseller or other finds out an indigent Hackney scribler to render it into English. But with what dis-reputation and abuse to the worthy Authors, every learned person cannot but observe.5

It was a bestseller in its day and went through at least six editions by 1703, being expanded several times.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

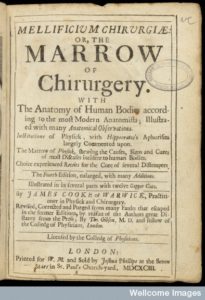

Gibson also edited the reissue of James Cooke’s Mellificium Chirurgiae: Or, The Marrow of Chirurgery (1693 and 1700) in which he saw his role as to ‘Revise, correct and purge‘ the text of the ‘many faults that escaped in the former editions, by reason of the authors great distance from the press‘. He also published an autobiography of his first wife, Elizabeth, along with her funeral sermon, in 1692.3

In his 70s Thomas Gibson took up a new phase of his career and served as physician -general to the army from 21 January, 1719 for the last three years of his life. He died on 16 July, 1722, aged 75, and was buried in London. He is thought to have left the sum of £30,000 to his nephew as his heir.4

Credit: thelondondead.blogspot.co.uk

____________________

- Gordon Goodwin, ‘Gibson, Thomas (1648/9–1722)’, rev. Patrick Wallis, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/10635, accessed 30 March 2017]. Subsequent biographical details are from this source unless otherwise stated.

- The Munk’s Roll (Properly called The Lives of Fellows) is a series of obituaries all members of the Royal College of Physicians created in the nineteenth century. It was compiled by the Harveian Librarian, William Munk from whom it takes its popular name. See http://munksroll.rcplondon.ac.uk/.

- Anon, A Sermon Preach’d on the Occasion of the Funeral of Mrs Elizabeth Gibson, together with a Short Account of her Life (London, 1692). Details of Elizabeth’s will are from Miscellanea Genealogica Et Heraldica and the British Archivist (1888), p. 195. Information about Elizabeth Gibson’s second marriage is omitted from Gibson’s ODNB and Munk’s Roll entries which refer to her as the widow of her first husband at the time of her marriage to the physician.

- http://thelondondead.blogspot.co.uk/2015_07_01_archive.html.

- The Anatomy of Humane Bodies Epitomized (London, 1682).

One thought on “Thomas Gibson’s Life and Times”

Comments are closed.