I have just got back from a lovely stay in Malta. I spent many hours learning about the military history of the Island, and went round the rather splendid Museum of the Knight’s Hospitallers. Although the museum doesn’t have very many historical objects, it uses dioramas and mannequins to paint a picture of the hospital during the early modern period. I was particularly pleased to see it didn’t fall into the trap of talking about how ineffective the medicine was and how doctors probably spent most of their time killing people.

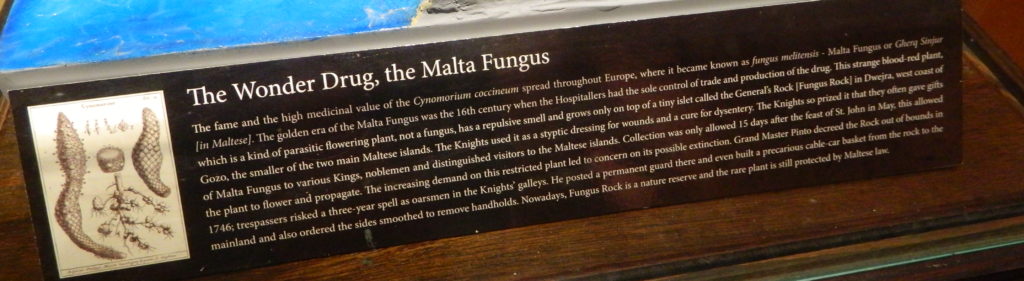

While learning about the work of the hospital and its surgeons I was fascinated by a small plaque explaining the use of a particular Maltese fungous for medicinal purposes. This was the second mention in a museum or the properties of specifically Maltese plants useful for treating military ailments – a plaque at Fort St Angelo had referenced a plant that flowered within the premises that had healed patients treated there. It was thought to be provided by God as the shape of the flower reflected the eight-pointed star of the order.

I won’t simply recite the museum’s description of the plant you can see it here. But I was particularly intrigued by the fact that access to the drug was restricted by physically altering the landscape so that people couldn’t climb onto the islet where it grew. The punishment for taking the plant – three years as an oarsman in the Knights’ galleys must have been pretty daunting, but perhaps didn’t put people off if they felt the need to constantly guard the plant.

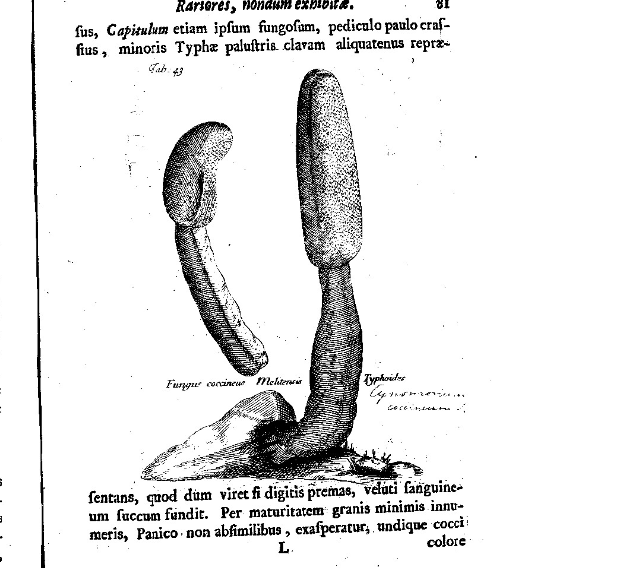

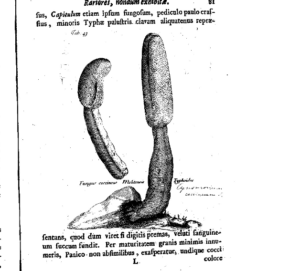

The fungus was mentioned once or twice in English language sources. A catalogue of the ‘Rarities’ belonging to the royal society preserved at Gresham Colledge, includes a note that ‘The SCARLET CATSTAIL MUSHOON [sic] of Malta. Fungus Typhiodes coccineus Melitensis was Given by Sig[noi]r Boccone, and by him desribed and figur[ed]’. This was accompanied by the following drawing.1 Although I have to say these images don’t quite look like the same thing.

Botanical writers were certainly aware of other plants originating on the Maltese islands. The Theatricum Botanicum, composed by John Parkinson and published in 1640 described two kinds of cumin said to be grown on Malta.

The first was the ‘Small Sweete Cumin of Malta‘ which was said to be like aniseed, but as sweet as fennel. This was put in the ‘bread or other meates’ of the Maltese people, and traded for other commodities. The second was the ‘Great Sharpe Cumin of Malta‘, which was described as ‘smelling more unsavourly and tasting hot quicke and sharpe, almost like Cubebs or Pepper’, than other varieties.

None of the medicinal virtues described were attributed specifically to the Maltese versions of the plants, but instead cumin was more generally described as aiding digestion and so removing humours from the body. The seeds could be used in a poultice to remove swelling of the scrotum caused by either wind or watery humours. Boiled in wine the seeds helped ease those who had been bitten by snakes.2

I do love it when holidays lead me to interesting early modern medical history!

___________

- Musæum regalis societatis, or, A catalogue and description of the natural and artificial rarities belonging to the Royal Society and preserved at Gresham Colledge (London, 1685), p. 239

- Theatricum Botanicum (London, 1640), p. 887.