The Athenian Mercury published in the 1690s was the first ever Agony Column in England. It followed a format that remains today and should be familiar to everyone – people wrote in anonymous letters asking for information and advice on a range of different topics. These questions and the editorial teams answers to them were published as a weekly periodical. Helen Berry, in her book on the Athenian Mercury, concluded that the concerns of early modern readers were not so different from our own, the body, courtship and sex, drink and drugs, and relationship are enduring topics of interest and concern.1 However, early modern correspondents did write some questions that would seem out of place today. For example, they questioned the existence of witchcraft and the efficacy of love potions.2

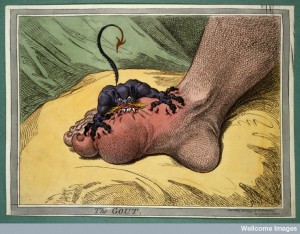

Many of the questions related to men’s bodies and their concerns about their health. One printed on Tuesday March 31st asked ‘What’s the reason that some Men have no Beards?’ to which the reply was given that some men lacked heat and moisture their bodies were simply of the wrong disposition. Another asked what is the ‘Original Cause of Gout?‘. ‘Gout is the product of Excess, and irregularities, especially in drinking some French Wines, and other sorts of Liquors that are saline and acid’, replied the authors.3

One question that I find particularly intriguing was published on Saturday 17th October 1691, in which a man asks about the physical response he experiences each time his wife is pregnant. He wrote,

‘Upon my Wifes conception I am immediately sick, and so continue every Morning `till she is quick [can feel the child moving], and bear equal Pains with her whilst in Labour: This is matter of fact, pray your Opinion of the Reason thereof?’

The periodical’s authors replied,

‘Our Thoughts upon it are these, That the Semen has potentially an Idea of every particular part of Humanity, and the Imagination in the Generative Crisis may be so great as to fix the Idea a great deal stronger than Naturally it is, even so far as to retain a sensible Communication to or from the whole mass from whence it is seperated [sic], so that whether the whole or the part suffers, the same is Communicated to the other by the aforesaid sense of the imaginary Impression’.4

Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

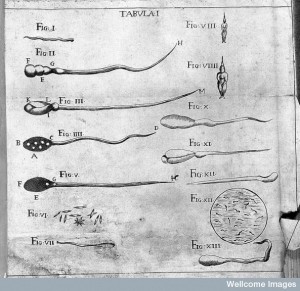

The authors of the Athenian Mercury did not reject the man’s claim to be experiencing the disagreeable physical effects of pregnancy alongside his wife as ridiculous or a flight of fancy. They did not even suggest that he was suffering from a disease or disorder that manifested the same symptoms as women experienced in pregnancy. Instead they drew on ideas about the properties of semen/seed in order to explain how this phenomena could have occurred. Although a much earlier text, Helkiah Crooke’s Mikrokosmographia described how seed ‘containeth in it selfe the forme and Idea of all the parts (for it falleth from them all)’. 5 This the authors suggested created a connection with man’s body that allowed the pains and nausea to be transferred back to the body that had produced the seed.

The authors also called the idea that the strength of the imagination could affect the process of reproduction. This is particularly interesting as it was nearly always the mother’s imagination that was thought to be both important and potentially dangerous. It was believed that at the moment of conception a foetus could be moulded and changed by a woman’s imagination. So Aristotle’s Masterpiece told readers that ‘nothing is more powerful than the imagination of the Mother; for if she conceive in her mind, or do by chance fasten her eyes upon any Object, and imprint it in her Memory, the Child in its outward parts frequently has some representation thereof’.6 This explained the birth of a woman covered with hair, whose mother had fixed her eyes upon an image of a Saint wearing a lion’s fur at the moment of conception. Similarly during pregnancy the woman’s mind was thought to imprint upon the child – so if she had an unfulfilled craving for a particular food the child might be born with a birthmark that reflected this.

The authors also called the idea that the strength of the imagination could affect the process of reproduction. This is particularly interesting as it was nearly always the mother’s imagination that was thought to be both important and potentially dangerous. It was believed that at the moment of conception a foetus could be moulded and changed by a woman’s imagination. So Aristotle’s Masterpiece told readers that ‘nothing is more powerful than the imagination of the Mother; for if she conceive in her mind, or do by chance fasten her eyes upon any Object, and imprint it in her Memory, the Child in its outward parts frequently has some representation thereof’.6 This explained the birth of a woman covered with hair, whose mother had fixed her eyes upon an image of a Saint wearing a lion’s fur at the moment of conception. Similarly during pregnancy the woman’s mind was thought to imprint upon the child – so if she had an unfulfilled craving for a particular food the child might be born with a birthmark that reflected this.

It is not clear whether the writers of the Mercury applied any negative, or particularly feminine, connotations to the over-excited nature of this man’s imagination. They had mixed the idea of very potent, and thus very manly seed, with the more womanly imagination. Thus, both the man himself and the authors of Mercury appear to be rather ambivalent about the gendered nature of this man’s suffering. The authors don’t make any overt comments about the fact that this man’s body was suffering from particularly female troubles and the man himself, albeit anonymously, willingly admitted to feeling morning sickness and childbirth pains in sympathy with his wife. Moreover, this husband, whoever he was, did not ask the Mercury how to ‘cure’ this problem or prevent him from feeling these pains, just. So we can assume that he was not excessively troubled by his experiences, or felt that it impeded his manhood in anyway. All in all it is not entirely clear what anyone really thought about a man suffering from excessive sympathy pains for his wife.

________________________________

1. Helen Berry, Gender, Society and Print Culture in Late-Stuart England: The Cultural World of the Athenian Mercury (Aldershot, 2003), p. xii.

2. Ibid.

3. The Athenian Gazette: Or Casuistical Mercury, Resolving all the most Nice and Curious Questions Proposed by the Ingenious: From Tuesday March 17th, to Saturday May 30th 1691, The First Volume, Treating on Several Subjects mentioned in the Contents at the Beginning of the Book. (London: John Dunton, 1691).

4. Ibid.

5. Helkiah Crooke, Mikrokosmographia (London, 1615), p. 200.

6. Anonymous, Aristotle’s masterpiece (London, 1684), p 25-7.

© Copyright Jennifer Evans, all rights reserved.

This is really fascinating. I’ve done some work on Irish advice columns from the 1960s onwards. Intrigued to read in your post that questions about sex featured in the columns of Athenian Mercury in the seventeenth century: there’s actually very little reference to this in Ireland until the latter half of the twentieth century. I wonder if you could elaborate: are they questions, for example, about problems conceiving or regarding intimacy, etc? Thanks!

Thanks Ciara, There were all kinds of questions asked some about conception, in one someone asked whether it was true that coffee could make you impotent/infertile. There was also a story about a poor husband who ran up debts and became impotent, he and his young neighbour therefore decided he should sell his wife to another man who would support him and his children – she perhaps unsurprisingly refused.

There was also one about a new married couple who knew they didn’t have enough money to maintain their lifestyle if they had children, so the man was ‘foregoing the pleasure’ of her until their fortunes has raised – they were asking if this was a sin.

There is also another book Aristotle’s problems, which is set out in the same style of questions and answers – but these probably weren’t written in – which contains lots on sex, conception, bodies and health.

Thanks for the reply. The variety of questions is really interesting, particularly the idea of sinning by not procreating. I recently came across a booklet from the 1930s that gave advice to new wives. One of the longer term pieces of information dealt with intimate relations after conception was no longer possible. Apparently, this was okay, but only if the couple came together with the aim of pregnancy. Bizarre!

Interesting – maybe we can do a comparison! There was some dispute in the early modern period about sex after conception. Some authors did say that a woman could conceive again – ‘superfoetation’ whereas as others said it couldn’t happen. They did acknowledge that people continued to be intimate though because they thought it could cause miscarriage.

In terms of barrenness, in early modern England it was not a reason for divorce or separation – along as sex could still occur – so it was expected that these men and women would still be intimate. Was part of their marital duties to provide due benevolence. similarly though, it was advocated that men and women should come together with the aim of conceiving.

There are also some great tropes about the dangers of post-menopausal relationships