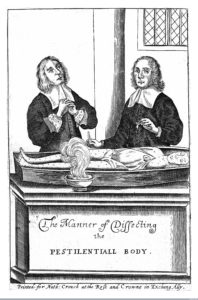

A short while ago now I examined Alice Dolan’s excellent thesis on linen and its various roles in the life cycle. This got me thinking a bit more about the materials used in early modern medical recipes. We have seen these in various previous blog posts – like the hats made to cure headaches and the various bandages applied to wounds. Often linen was mentioned as the material of choice. As Alice has shown linen was an important fabric for most people’s daily lives. It was therefore on hand to be used in medicine. Moreover linen was associated with cleanliness and was thought to draw corrupt matter, dirt and fluids away from the body.

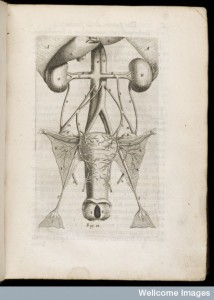

A collection of late 17th and early 18th-century papers belonging to the Talbot family of Lacock now housed in the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre reveal that at least one member of the family suffered with the piles and was sent remedies and suggested cures by several acquaintances. Given the sore and delicate nature of the condition it is little wonder that the patient sought soothing ointments and lotions. It is also unsurprising that the recommendations he received included suggestions for using soft fabrics as an applicator.

The suggestion sent by Lord Fitzwilliams was to take some linen rags and make bags filled with the powder of beaten gall. The bags were then soaked in ‘sallett oyl’ (olive oil). The patient should then apply a bag to the ‘fundament’. Once it dried out it was swapped for another pre-soaked bag.1

Another remedy on the same piece of paper required a finer, softer fabric – but not because of the delicate nature of the patient’s backside. Instead Lord Orkney advocated making a bag of silk or linen containing orpin roots (a purple-flowered Eurasian stonecrop) that was worn ‘on the breast’; the leaves of the plant were steeped in milk and applied to the affected area.2

These materials remained on the outside of the body, but another piece of paper in the collection offered much more detailed instructions for internal applications. Again here the material used was important at the author – whose name unfortunately has been torn off – was clear that ‘fine flaxen cloath’ had to be used. The note read as follows:

Honnored Sr

I have by ye boye sent you some Balsam of Pilewort, ye best way of useing it is by dipping a fine flaxen cloath or over worne Holland, in ye Balsam at night when you goe to bed, & applie it to ye part grieved, & if you perceive them to be within ye body; fix ye cloth upon a probe or some other convenient instrument, & conveigh it, two or three Inches up & leave ye end of the pledgett or cloath out, & [?] not in the least doubt, but you will have ease in a moment, & a cure in a few dayes wth yis hasty wishes of yo[u]r obliged friend and humble servt to command

Bandages soaked up the body’s fluids and held the skin in place. Linen and fine cloths were also used to apply medicines to sore and broken skin, the texture and feel of these fabrics were probably very important, important enough to specify in letters.

____

- Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre, 2664/3/4k/5 /21

- Ibid.

Another reliably excellent and entertaining blog Jen… but all I can say, fundamentally, is ouch!

thank you Jonathan, that is mostly what I thought when I read them in the archive!