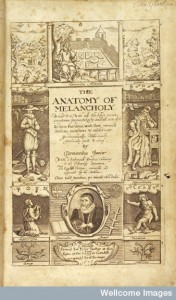

In 1621 the scholar Robert Burton published The Anatomy of Melancholy. In this weighty tome Burton presented a medical discussion of the disease Melancholy (what would now cover a range of conditions including depression). The English translation of Lazare Riviere’s medical text outlined that ‘Melancholly is a Doting or Delirium without a Feaver with fear and sadness.’1

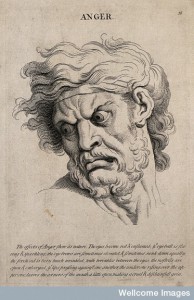

Seventeenth-century medics explained that melancholy was caused by a build up of the humor ‘Black Bile’ inside the body. Indeed black bile was also known as melancholy. In the eighteenth-century some medical writers offered alternative explanations of the disease. A treatise of Richard Baxter’s works described how people could be cast into the condition by a fright, the death of a friend, some great loss, or sad tidings. The mind then disorders the passions and disturbs the spirits. This in time corrupted the blood bringing the body’s condition in line with the mind.2

So how did patients manage and attempt to cure melancholy?

Haemorrhoids

Lazare Riviere warned readers that the ‘Disease is dangerous’ if it became chronic. He explained that once it was established it was difficult to cure. But new melancholy was ‘easily cured’ and managed. He suggested that baths of sweet waters would help. In other cases melancholy required no intervention because if a melancholy man developed hemorrhoid’s this would cure him.3 Haemorrhoids removed the build up of black bile in the body. This released patients from their obsessive thoughts and fixations.

A book attributed to Nicholas Culpeper agreed that ‘Hemrhoids coming on such as are mad or molested with black Choller, … are good’. But the author warned that ‘if they bleed too much there is a great danger, for they threaten a Dropsy’.4

Vomits and Medicines

Medical texts listed a range of remedies designed to ease the symptoms of the disease. Michael Ettmüller, a German physician, suggested that ‘The Foundation of the Cure of Melancholy consists in Emeticks‘ [medicines that make you sick. He also stated that melancholy patietns ‘hate their Physicians’ – perhaps little wonder if he was making them sick with ‘large Dose[s]’ of emetics.5 If being repeatedly sick didn’t appeal, several other remedies were avaible. First ‘The juice of Ground-Ivy taken inwardly … every day, is very much commended to cure this Distemper’. The same juice could be applied as a liniment rubbed onto a shaved head. Another option was a ‘Tincture of Hypericum‘ or St John’s Wort, which was believed to be particuarly beneficial.6

Flattery, Humour, and Distraction

Another was to manage the depressed moods associated with melancholy was to find a distraction. Burton himself managed his condition by writing and producing The Anatomy of Melancholy. Writing about the self and emotions allowed him to work through his emotions.

In the eighteenth century readers of the Athenian Oracle a collection of questions and answers (originally produced in the Athenian Mercury ) were offered a summary in answer to the question ‘What is Melancholly? What are the Symptoms, Causes and Cure thereof’. The book repeated the medical definition that the condition was ‘A Raving without Fever or Fury, with Fear and Sadness‘. The authors advocated a cure similar to Burton’s writing therapy. They advised that ‘if the Brain be disaffected with deep thinking on one particular Object, turn the stream, if possible, to something else, Flatter, humour, or do what you can for the same end’. For sadness, though, the patient was to be frightened as ‘Fear is the best Cure’.7 Fear roused the mind and so assisted nature to cure the patient.

William Forster, whose book was published in 1745, also suggested distracting the patient with ‘Chearful Conversation’ and exercise. He recommended clear air and horse riding to help the patient.8

There were, then, several methods for managing melancholy in the early modern period, not all of which required writing an excessively large tome on the condition.